January is upon us and with it the start of several weeks of bone-rattling cold and snow-cancelled classes erroneously dubbed “Spring Semester.” For me, it heralds the beginning of a poetry class I teach at the University of Virginia, whose goal, to paraphrase the title of Edward Hirsch’s wonderful book, is to teach students how to read a poem and hope they’ll fall in love with poetry. This is a required course, so I can’t count on any initial enthusiasm on the students’ part. Instead, I expect to encounter resistance, suspicion, indifference, and even downright repugnance toward the art.

January is upon us and with it the start of several weeks of bone-rattling cold and snow-cancelled classes erroneously dubbed “Spring Semester.” For me, it heralds the beginning of a poetry class I teach at the University of Virginia, whose goal, to paraphrase the title of Edward Hirsch’s wonderful book, is to teach students how to read a poem and hope they’ll fall in love with poetry. This is a required course, so I can’t count on any initial enthusiasm on the students’ part. Instead, I expect to encounter resistance, suspicion, indifference, and even downright repugnance toward the art.

I begin on a deceptively light note with Billy Collins’ trenchant poem, “Introduction to Poetry.” The speaker is a frustrated poetry teacher who suggests a number of strategies for getting beyond surface arguments and penetrating the sensual and irrational dimensions that make a poem a poem. He tells his students to “hold [a poem] up to the light/ like a color slide,” to “press an ear against its hive,” to “drop a mouse into a poem/ and watch him probe his way out.” Despite this good advice, however, old habits are hard to shake. As Collins opines,

But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

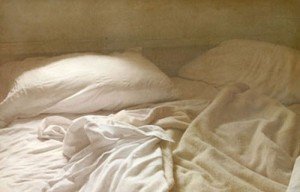

My students generally respond cheerfully to this poem. They grasp the necessity of looking at the poem’s visual imagery, listening to its music, probing its structure. After all, if what the poet wanted was to make an argument, he could write an essay or a letter to the editor. But a poem is not an essay. There will always be something in the poem that eludes rational discourse. As the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam famously wrote, “Where paraphrase is possible, the sheets have not been rumpled. Poetry has not spent the night.” The students seem accepting of these ideas, even a bit jubilant. Something new has been revealed which has begun to liberate them from their fears. We have discovered that poetry isn’t an arcane riddle whose meaning must be painfully extracted.

Then we spend the rest of the semester paraphrasing poems and talking about what a poem means.

Yes, of course, we explore “poetic devices,” imagery, tone, language, sound orchestration, where a poem picks us up and where it deposits us. Yet inevitably someone will ask, “So is the poem saying that x=y or that x=z?” What does the poem mean?

Why does this happen and is it really so reprehensible? Poetry is a new language for most of the students – many languages, actually, if we consider the unique rhythms and vocabularies of each poet’s work. And when we learn a new language, we need to keep our feet on the ground. We want to know the basic sense of what we are hearing or reading before wandering off into fields of subtlety, allusion, and, worst of all, poetic ambiguity. The notion that both x=y and x=z might be true and that the poem is pointing to the irresolvable contradictions of life, is just plain unpalatable to many.

While some of us have that ample tolerance for uncertainty that Keats called negative capability, many of us – most perhaps – do not. We are creatures who cannot help ourselves. We want to know what things mean.

Sharon Leiter, Poetry Editor

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.