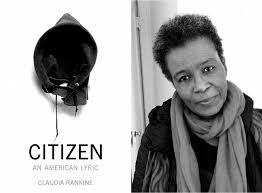

December is always a good time to add to my already long list of books to read. There are awards nominations, various reviewers’ choices for best books of the year, random recommendations for books people are giving or would like to receive as presents. One of the books that appeared frequently as I scanned these sources was Citizen by Claudia Rankine. I was already asking for Marilynne Robinison’s Lila and Richard Ford’s Let Me Be Frank With You for Christmas, so I bought Citizen for myself. I’m glad I did—sort of.

Citizen was among the finalists for the National Book Award in poetry for 2014, but to refer to it as a book of poetry may be misleading. For one thing, it is a collection of prose poems that often blurred in my mind any distinction between prose and poetry. It also included enough visual art that it is easy to think of it as mixed media. More important though than the fact that Citizen doesn’t fit neatly into some category is that for me the book was challenging in ways I don’t usually expect a book of poetry to be. Some poetry is more satisfying than challenging, perhaps because of its beauty or insight or some other quality. Some poetry is challenging for me because I simply have trouble understanding it. Citizen is challenging because all too often I do understand it.

I will not presume to offer a review of Citizen. I am in general not qualified to offer reviews of poetry. And In the case of this particular book, what I feel is being asked of me is not analysis, opinion, commentary, or anything that allows the reader to stand apart. Rankine asks me to interact with her words, to be engaged, not to parse.

I will choose two of my several points of engagement. I frankly did not know until I read this book that there is a recognized medical term, John Henryism, named after the African American folk hero who killed himself outworking a steam drill in the building of a railroad. The term refers to the idea that one reason hypertension is much more prevalent among African Americans is that they work harder, sometimes work themselves to death, trying to prove themselves in a world that often does not recognize or value their contributions.

I should make clear at this point that Claudia Rankine is an African American woman and Citizen is a book that is all about, and uncomfortably about, race. I wanted to argue with her reference to John Henryism. Aren’t all sorts of people workaholics? Don’t women also find that they have to work harder to be recognized? (Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did but backwards and in high heels.) Don’t a very great many people adopt unhealthy strategies to try to prove themselves to someone?

Perhaps that is all so, I say to myself, but making those points also has an uncomfortable feel to it. It has the feel of being dismissive of this woman’s voice, of being dismissive of the role her race has played in her interactions with her society, of being dismissive of the whole history of the way African Americans have been treated in the workplace, dismissive not so much of the facts and figures about health disparities or employment discrimination but of the ways race affects our inner lives. These are poems about the souls of black folks. They are also about the souls of white folks.

The poet testifies to repeatedly having to wonder. A man cuts in front of her at the checkout counter and when confronted says, “Oh, I didn’t see you.” An employer calls her by the wrong name, the name of the only other black employee in the office. A credit card is handed back to the white patron in the restaurant booth even though it was the black woman who had tendered it. Innocent mistakes? Products of thoughtlessness or inattention or mere accident? One by one the case for innocence can be made. When the incidents pile up on top of each other, pile up on top of personal histories and social histories, one does have to wonder.

As in the case of John Henryism, it is possible to universalize the experience. Any one of us can be made to feel invisible for all kinds of reasons or for no reason at all. We know, most of us do, what it is like to be looked past or through. It doesn’t necessarily have to do with race. But then again it doesn’t necessarily not have to do with race. The wondering is ours too.

Toward the end of her book, Claudia Rankine writes: “Yes, and this is how you are a citizen. Come on. Let it go. Move on.” And we do, all of us do, move on. Because we have to. But not without questions.

–Jim Bundy

Jim Bundy lived in Chicago for thirty-five years as a student, minister, and college teacher. He moved to Charlottesville in 2000 where he served as pastor of Sojourners United Church of Christ for 10 years before retiring. He is the author of two books, one an historical study, the other a collection of sermons. He continues to reside in Charlottesville.

Follow us!

Share this post with your friends.