The view from the bus station was disappointing. All I could see was the traffic on Calliope. That, and the bottom of the Causeway, all concrete and metal, darkened by decades of weather and exhaust. The fall air was saturated with car fumes and diesel: a smell that always gave me a headache.

I sat, as patiently as I could, on a metal bench that was peppered with rust and dried bird shit. I waited and hoped that Mary remembered I was coming. Eventually, I saw her working her way towards me, weaving between the parked cars and people. She looked different than I remembered, but I didn’t know how.

“It’s been a long time,” Mary said in place of a greeting.

“Only two years.”

“Two years is a long time.”

She led me to her car and I struggled with what to say. I tossed my bag into the back and settled myself into the passenger seat.

“Where do you want to go?” she asked, turning the key in the ignition.

“Let’s go see Kaylee.”

She seemed surprised, but checked her watch anyway. “We have some time to kill before it opens.”

“Fine. Can we just go for a drive? I’ve been in Minneapolis for too long, I want to see the sights.”

Mary eased the car into the traffic and merged her way onto I-10.

I could tell that she was mad at me. I wondered if her anger would ever dull. Still, she had come, and that had to mean something.

She steered towards the heart of the city. Not downtown with its few squat skyscrapers that looked like dull gray tombstones from a distance, but to the real heart of New Orleans.

We crossed the river. Tugboats and barges were sprinkled on the green-brown water of the Mississippi like so many fallen leaves.

We crossed the river. Tugboats and barges were sprinkled on the green-brown water of the Mississippi like so many fallen leaves.

Everything was different and new, or old and dirty. Billboards lined the highway, announcing shops and restaurants that had reopened. Harrah’s shouted its 24-hour gambling, the lotto jackpot had reached a hundred million dollars, and strip clubs were offering all-you-could-eat crawfish. Signs everywhere proclaimed love for the Saints.

But for every inhabited building, more were closed, their windows and doors boarded up with sheets of graying plywood. Last messages, like epitaphs, were spray-painted on the weathered boards. Signs of the times, some were warnings to looters and others were messages of hope and rebirth. Tattered blue tarps covered gashes on roofs like haphazard patches. Even from the highway I could see the Katrina tattoos on houses that marked the number of bodies rescue teams had found inside.

Shopping mall parking lots were filled with dumpsters pockmarked with rust, instead of cars. Entire neighborhoods that I remembered from before were gone, only weed-filled lots and concrete slabs were left behind. It hurt to remember the things that were no longer there.

I looked at Mary.

The city was in ruins, but she didn’t seem to notice. She just drove; her gaze never left the road.

Although I couldn’t see Lower 9 from I-10, I’d seen the news: hundreds of house trailers arranged like a potter’s field. Another section of the city, the Musician’s Village, was filled with cookie-cutter houses painted a variety of gaudy colors. Sad jazz music leaked out of that neighborhood.

“So, you were fired?” Mary asked.

“So, you were fired?” Mary asked.

“Last week. They didn’t even give me severance.” I had been in Minnesota for a marketing position, finally putting my degree to use. With the economy, they had to cut back and the new hires were the first to go.

“I’m sorry. I know how much you wanted that to work out.”

“Thanks. But we both know that I wasn’t there for the job.”

The Superdome loomed in front of the clustered skyline, its landscape was startling. Different shades of concrete had taken the place of the once beautiful greenery that had been uprooted by the storm.

“Maybe I shouldn’t have come back,” I said as we drifted by the Dome. I hoped that she’d respond; maybe tell me that she was glad that I had returned, that this is where I belonged. Instead, Mary slowed the car and took the ramp to the French Quarter.

“It doesn’t even look like this area was touched.”

“It wasn’t. Not really. A few bars even stayed open the entire time.”

“How could some people just sit around and drink while everything they cared about was taken away?”

This question drew a sideways glance that I ignored as best I could.

We parked off Decauter and walked towards the Square. Mule-drawn carriages mixed with the traffic. The clopping of hooves resonated on the asphalt and blended with the sporadic honking of car horns. I could even hear the whistling of the Natchez steamboat coming from somewhere on the river. Street musicians and performers lined the fence that surrounded the Square. Fortune tellers, palm readers, and crystal ball gazers milled around, begging to predict our futures.

The scent of roux, chicory, fried dough, seafood, and the river combined with dozens of other smells to create the Quarter’s own decadent incense. I inhaled again and again. The fragrance was overwhelming and filled me with a mixture of longing and remorse and a hundred other emotions.

The Saint Louis Cathedral overlooked Jackson Square and the river beyond. Its spires lanced the sky – an image from another time.

“Did you know that the statue behind the cathedral was damaged?” Mary asked as we passed the bronze of Andrew Jackson sitting on his horse.

“No.”

We walked down Pirates Alley, careful not to bump into each other on the cobblestoned path wedged between the cathedral and the old city hall. I looked through the bars of the wrought-iron gate into the garden, but I couldn’t see anything wrong with the statue. Jesus’s arms were spread wide in welcome, as if forever awaiting an embrace from the city.

“What’s wrong with it?”

“A thumb and finger were snapped off. The bishop said that it was symbolic of Jesus turning away the storm, preventing Katrina from completely destroying the city.”

I looked again and saw that the same fingers that had rubbed spit and dirt into a blind man’s eyes to restore his sight were gone. I wondered out loud why the statue hadn’t been repaired.

“I guess they wanted to leave it as a reminder.”

“As if there aren’t enough already.”

Still, I kept thinking about that image. About the fingers of Jesus flicking away the storm and being torn off in exchange. About how some things could even hurt God.

On the edge of the Quarter, the crowd of tourists thinned and the buildings transitioned from two-stories to camelbacks: shotgun-style houses with humps of a second level.

One house’s front porch was sagging in, its roof collapsed, and its beige paint peeling off like dead skin. Dirty teeth of glass grinned from windows. One side of the house had been ripped away, revealing rotten two-by-fours that looked like splotchy, diseased bones. At this sight, I wondered what had become of our old house. If it was like this or if it had been bulldozed like so many others. All of those memories gone.

Kaylee loved that house. Her window had looked out on a towering live oak: a tree that was the inspiration of many of her art projects. Her walls were covered with drawings; most of them doodles of twisting branches and the small house behind it. I still had one of Kaylee’s kindergarten creations. A stick figure trio labeled “Daddy, Mommy, and Me” on red construction paper. The figures of daddy and mommy were holding hands. Kaylee’s self-depiction was of a little girl with long Crayola-black hair, bright green eyes, and a great big smile. And there, in the background, was the live-oak.

The remains of Storyville, the city’s original red-light district, surrounded the cemetery like a ring of mourners at a funeral. Empty flophouses were waiting to be demolished, having been abandoned long before the storm. Even the homeless had abandoned Storyville. There was something unsettling about having a graveyard as the heart of a community.

Still, before Katrina and before Kaylee got sick, we came to the cemetery every weekend. We’d walk the same path that Mary and I had taken, soak up the smells, sounds, and sights of our city. Then, we’d get some po-boys and picnic in the cemetery. Mary and I would sit on a bench while Kaylee ran around and explored.

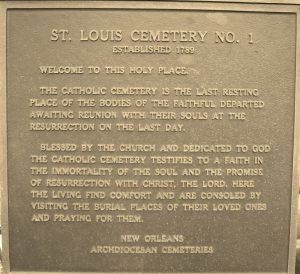

Seashells poked out of the surface of the brown wall that enclosed the cemetery. The lower half of the wall was a dirty brown, where a blurry line from the floodwaters had risen and leveled off. Next to the gate was the bronze sign, tarnished and dark, that I always stopped to read.

I pushed open the gate and stepped down into the city of the dead. Mary dropped a wrinkled bill into the locked collection box and followed. I tried to remember if she had always done that, but I couldn’t.

Aboveground vaults and distant mausoleums rose like miniature temples. Long shadows stretched from the vaults toward the entrance.

Each vault was like an oven. A body would be interred and, within a few months, the Louisiana heat would bake the corpse, drying it up until only the bones were left. The bones were pushed to the back to make room for the next body. In this way, an entire lineage could share the same tomb.

The vault of Paul Morphy and his descendants was marked by dozens of little chess pieces. His vault was a miniature battlefield. The faceplate was engraved with “The Pride and Sorrow of New Orleans.”

Mary and I used to sit here and guess what that inscription meant while Kaylee played with the chess pieces, pretending that they were little ponies and princesses, instead of knights and pawns. We agreed that he must have been some chess prodigy but that he gave up playing so he could spend more time with his true love.

Eventually, driven by curiosity, we looked him up. He was widely regarded as the best chess player in the world before he turned twenty. He retired from the game when he was twenty-two because it was too easy for him. Despite the city begging him to keep playing, he never played competitively again. He died of a heart attack twenty-five years later, barely remembered.

We liked our version better. I wondered if Mary remembered it.

We passed the tomb of Marie Laveau, the first voodoo queen of New Orleans. Her grave was marked with graffiti, while birthstones, seashells, tarot cards, flowers, gris-gris bags, coins, a bottle of Abita beer, and fly-covered Cajun food lined the perimeter of the vault.

The first time we brought Kaylee to the cemetery, we had to pry these keepsakes from her fingers. She didn’t understand that they weren’t for her. They were gifts from the people of New Orleans. The gifts, Mary explained to our daughter, were given in thanks for answered prayers.

“I can’t believe people leave stuff here,” I said.

Mary’s eyes involuntarily looked at the bottle of Abita beer.

“Sometimes prayers are answered.”

I got the distinct impression that she had left the beer there for me. That her prayers were for me. Abita used to be my favorite.

The pathways twisted and turned around the closely packed vaults. Loose pieces of marble and brick littered the ground like plastic cups and beer cans on Bourbon Street. The rubble increased the closer we got to the middle of the cemetery. Entire parishes of the cemetery were swamp-like with deep, standing water and black mud that smelled like decay.

“Why is it like this?” I asked, astounded by the disrepair. “It didn’t used to be like this.”

“I guess nobody cares anymore.”

Mary led the way through the maze-like graveyard with ease. It was another sign that she visited often. I felt a pang of guilt. It was the first time I had been back since the funeral.

The path turned and opened. A live oak tree was surrounded by tall, crumbling tombs.

“I love this tree,” Mary said. “It’s my favorite part of the city now.”

“I love this tree,” Mary said. “It’s my favorite part of the city now.”

“Why?”

She didn’t speak for a second. Finally, she answered, “It reminds me that even something broken can be beautiful.”

Several branches were missing, torn off like the fingers of Jesus, leaving jagged amputations behind. A black lightning burn marred the wide, ancient trunk. Dead limbs and wood chips covered the ground like mulch.

Drooping, low-hanging branches almost touched the ground before they arched back up over the tombs. Roots clung to the brick and marble like grasping fingers. The twisting branches created a canopy of speckled light. Spanish moss hung from the limbs like loose strands of gray-green hair. It was both beautiful and sad. The broken tree clung to life so hard in the middle of a place of death.

The tree was part of the reason Kaylee had loved this place so much. Back then, it was stately, and its curving boughs practically begged to be climbed.

We moved on, ducking branches.

The first mausoleum was a towering structure built hundreds of years ago for the city’s poor. In front of the granite crypt stood a faceless statue, guarding the weary and dejected in death. An ornate wrought-iron fence topped with rusted crosses guarded the building filled with the remains of the victims from the many plagues that had ravaged the city: cholera, typhoid, diphtheria, malaria, smallpox, Bubonic plague, and yellow fever.

“New Orleans has been through so much,” I said.

“We always get through it though. We can always make things better if we try.”

Her comment was for me.

When Kaylee got sick, I checked out. Left. Not just New Orleans, but my family. I couldn’t handle it. Mary had never forgiven me.

We stood in silence before a large vault for the children’s hospital. The vault had housed our daughter but I knew that her body wasn’t there anymore. Not really. Her body was gone, cremated by the New Orleans heat. Some other father’s daughter was in there now.

For a moment, there was peace: my breathing, Mary’s breathing, and the quiet of the dead. I was almost tempted to reach out and hold her hand. The silence rose, threatening to overtake us, and then a car horn broke in.

“Do you want to get a drink?” she asked.

“I don’t drink anymore.”

On the way out, I noticed an empty space where yellow flowering weeds covered the grass. I took some comfort that there was still room in the graveyard.

Share this post with your friends.