Michael fled his village in South Sudan at the age of five. He trekked a thousand miles through war zones to arrive at a series of refugee camps where he lived for a decade. As a child at Kukuma Refugee Camp, Michael played soccer using a blown up latex glove fished from a trash bin outside the hospital tent. He learned to play chess and checkers under the punishing sun from old-timers who sat bereft of their children and their land.

One of the most life-negating situations a person can face is to live without a sense of a future. Added to the threat of war breaking out, attacks from hostile tribes, lack of food and water, recurring malaria, typhus, tuberculosis and a host of other diseases, day to day existence is dire in the remote desert climates where refugee camps like Kakuma are located. “Living in a refugee camp means that your life is on hold. Once I came to the States, I was able to plan ahead, to have a future,” Michael told me.

In a deal brokered between the U.S. and the Southern Sudanese leader John Garang, who died in a mysterious helicopter crash, Michael received political asylum to the States along with approximately 4,000 other unaccompanied minors, the so-called “Lost Boys.” We met when One Book, One Philadelphia chose Dave Egger’s novel What is the What about Valentino Achak Deng, another “Lost Boy” of Sudan for the city-wide book club. One Philadelphia asked me to choose ten of my undergraduate creative writing students at Drexel University to interview ten Sudanese immigrants for a City Paper series. Michael was the first of those interviewees. We became fast friends. Soon he asked me to write a book about his life.

In a deal brokered between the U.S. and the Southern Sudanese leader John Garang, who died in a mysterious helicopter crash, Michael received political asylum to the States along with approximately 4,000 other unaccompanied minors, the so-called “Lost Boys.” We met when One Book, One Philadelphia chose Dave Egger’s novel What is the What about Valentino Achak Deng, another “Lost Boy” of Sudan for the city-wide book club. One Philadelphia asked me to choose ten of my undergraduate creative writing students at Drexel University to interview ten Sudanese immigrants for a City Paper series. Michael was the first of those interviewees. We became fast friends. Soon he asked me to write a book about his life.

I found him to be in possession of a rare sense of optimism that I couldn’t help comparing to my own relatives and neighbors who had escaped pogroms in the early 1900s or death camps in Europe during the Holocaust. Considering that they came from different parts of the world and experienced different traumas, this shared characteristic struck me. Then I realized, this is the indomitable spirit of a survivor, this is what it takes to survive. And I wondered how many of us have it.

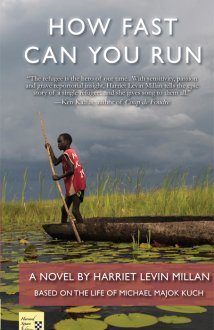

As I was finishing the novel that would become How Fast Can You Run, South Sudan was about to become the world’s newest nation. After twelve years in Philadelphia, where Michael attended college and graduate school, he yearned to return home.

I traveled to Juba to visit him in 2011 and witnessed the euphoria that seized everyone. Something miraculous was happening. A new nation was coming into being after a civil war between the north of Sudan and the south of Sudan that had started when Sudan was first declared an independent country in the 1950’s.

But now that the South has gained its independence, its dreams are on hold again, and not because of the North. The fighting is internal. The Vice-President is in hiding. The lines of contention are split between Dinka and Nuer, the two dominant tribes in South Sudan. “Alongside the civil war raged southern fratricidal conflicts,” National Geographic reported in a 2013 article about the region, “the most bitter fighting between Dinka and Nuer factions.”

According to Aljazeera, the number of South Sudanese refugees in East Africa could hit one million this year. “Nearly 1 out of 4 South Sudanese has been forced to flee for their lives.”

One reporter wrote that learning about the plight of refugees puts the vagaries of “her own life in perspective.” We know this view. It’s the one that continues to alienate us from the suffering of others.

I want to put forward a different view. I named my novel How Fast Can You Run (instead of Shake Loose the Scorpions, a title I loved suggested by the poet Kate Sontag) because I did not want the title to make the book sound like it was happening to people other than ourselves. I want to help cultivate compassion, encourage involvement in campaigns to open borders and aid refugees. I want my book to reverberate: this can happen to you or me, it can happen to anyone.

May the hostilities end, may the people of South Sudan be restored the peace they deserve after so much suffering and travail, after so much dispersion and bloodshed. And here in the U.S. as our cities become divided and as acts of unpredictable violence become predictable may we all heed the lessons.

Share this post with your friends.