Two 584-million-mile trips around the sun—the only traveling any of us could do. Two sets of birthdays and anniversaries and seasonal accoutrement. Innumerable sleepless nights. All spent in pandemic hibernation. In terror. On the brink of insanity. It’s fitting that they’d bring me back. Just like they always have.

When the clarion call came, it rattled like a cruel tease. After one cancelled tour and another doomed returning-to-normal show amid countless are-we-there-yet moments, the prospect of real-life anything seemed out of reach. I wasn’t ready anyway, still subsumed by a pandemic-induced Stockholm syndrome. But as soon as I saw the new schedule of shows, something in me cracked, letting in a sliver of light that beckoned to me with its familiar, beloved pull. I had to go. It was, after all, the Afghan Whigs. I didn’t really have a choice.

Some people follow sports teams, and some people join book clubs. Some people day drink. Me? I have a band. I started listening back in my grunge-laden Salad Days, making their acquaintance with the seminal album Gentlemen, and surrendering my heart somewhere inside Black Love. I collected every record over the following decade or so, including Greg’s side projects and solo work, but it wasn’t until the quiet years, after the band had called it quits, and I had lost direction on the road to myself, that I experienced the full force of the music. Alone. In my car, at my desk, staring down a blank page at 3 a.m. The truth is, I never minded the alone part. I was into distancing before distancing was a thing.

By the time the Afghan Whigs reunited in 2012, I had become a different kind of fan, still listening alone but seduced by the anonymous ease of the internet and ready to engage in the band’s rebirth, if not my own. I stumbled upon an online group of like-minded, longtime aficionados, which gave me an opportunity to share our love of the music and socialize from behind the screen. I guess social media really is Gen X’s milieu, because at no point in the past had I considered joining a fan group. It seemed so Tiger Beat.

Ten years have passed since then, and to my astonishment, participating in that group has defined a big chunk of my everyday. It seems like as we get older, surprises get more dire on the whole, but this one proved that the unexpected can still amaze. I didn’t just join a fan group—I made friends. In a place I never expected to find them, in ways I never thought I’d connect.

Our members are some of the dearest people I’ve encountered in this life. We bond over the music, of course, but I’ve also seen fellow fans give away tickets and merch, support personal creative endeavors, and donate to worthy causes. Like any group, we have pockets of dysfunction—and we’ve had our share of tense discussions over the past few years—but overall, the expressions of kindness and encouragement vastly outweigh the morose. There’s some genuine goodness there. Is the music really that magical? Don’t tell anyone, but I kind of believe it is.

When we couldn’t attend shows for literal years, hostage to that gruesome, politicized microorganism, we jointly endured purgatory, waiting to find out if we were, in fact, coming up on the end times. We commiserated over the lost tour of 2020. We reminisced and posted photos and videos while we stirred inside the storm. We watched Greg’s live set broadcast from an empty, lonely room as a single audience through a thousand individual screens, drunk on the elation of seeing and hearing but trapped in the stream of sadness pervading every thread that held us together. Would we ever actually see the band, or each other, again? The possibility of never weighed on my mind fiercely during those months.

The friendships I’ve forged with other fans are as unique as my experience with the music. I can talk about anything with these women, unfiltered and unjudged. Unburdened. Maybe it’s because we get together so irregularly. We don’t know any of the same local people or share family we must account to. Our history is recent and site specific. We can bring what we want to every encounter, even as we leave behind whatever we need to. In my maudlin-prone head, the idea that we found one another through music, because of one artist in the infinite sea of artists, is nothing short of miraculous.

We’re scattered across the country, dotting the states on both coasts and in between. We have spouses, children, pets, careers, and otherwise complete and fulfilling lives that roll on independently of the others. Like the shows, our visits are condensed, intense, and renewing. The first time I flew off to a new city to see a show and meet them in person was an adventure unlike any I’d ever anticipated—and one I needed more than I knew. As soon as I walked into our communal Airbnb, the sense of belonging edged out my fear. We shared perfume and borrowed hairdryers and poured wine as if we’d been together for years. After that, hanging out with them became an integral part of my show-going experience. With every new tour, we’d drive and fly here and there, attend shows in hometowns and random cities, and for an all too brief span, our planets would align. Then, in 2020, like the world, it stopped.

So dozens of months later, when our band announced a new tour, I knew the time had come for me to return to civilization. Scary as it was, I couldn’t refuse my existential need for nourishment. Because this music—an alchemy of words and notes and ineffable charm—reminds me to live. And these people—my sisters—remind me that it’s okay. And they all conspire to light up my heart and mind unlike anything else does. I had no choice.

I wondered though, how things might have changed after our mandatory hiatus from sharing oxygen and space and music. I questioned whether the shows would still take us to that same secret, scintillating utopia. I thought about who we’d be now, as a synergistic force of band and audience basking in the sublime glow. If we’d be healthy and sane enough to congregate in that music-filled, soul-searing happening that tosses the storm-ravaged parts of us back onto land for a few glorious hours when time stops and fear evaporates and we are destroyed and remade in the most astounding way.

From a more practical standpoint, I wondered how it would feel to stare up at the stage, half my face potentially obscured by a mask—every mirrored lyric, every knowing smile hidden from view. Should I even wear a mask? Would I be the only one? The pervasive query of whether we’d all get sick still hung in the air like the viral particles that put us here in the first place. We’ve been through various circles of hell over the past two years, and we’re carrying the weight and showing the scars of our scourged existence. Would the shows free us of that or cement into place how damaged we’ve become? Would returning to civilization be worth it?

In the end, I kicked my apprehension to the curb and bought tickets for five shows—two in the spring and three in the fall. Carrboro, Indianapolis, Chicago, Cincinnati, Asheville—all the usuals and a few new spots. I booked flights and reserved rooms and coordinated with the ones who make me brave enough to board planes and stand in the front row and embrace what it is to be me. And then I almost backed out—several thousand times. But the pull of my passion, the memories of before, and the temptation of simple joy nudged me forward, toward civilization, however tainted it might be.

When I finally got to that first show, vaxx card in hand and mask at the ready, not-quite-normal felt feasible. And when I stood in the cool, dark space, surrounded by my crew, the stage bathed in incandescent twilight and the floor confident under our feet, it was at once reunion and new beginning. We’d been gone one day shy of forever, but somehow, we hadn’t missed a beat. I was home. I’m always home as soon as the lights go down, and John, Rick, Patrick, and Jon (now Christopher) take their places. As soon as Greg swaggers up to the mic, and that first note sizzles from the guitar strings, drawing forth his words, awesome in awesome’s truest sense. It is both invocation and assuagement. The pain is over, at least for a time.

Over an hour and a half, suspended in sonic ether, we stood at the rail and sang and danced and felt the magic, absorbing every sound and spark and fleeting eye-to-eye greeting. They played songs from the new album. “Jyja” wrestled my senses to the ground, and “Please, Baby, Please” speared me right in the gut. They played old favorites. “Summer’s Kiss,” check. “Gentleman,” check. “Son of the South,” check. The crowd thundered out the final “Fountain & Fairfax” and clapped in unison through the first verse of “Oriole,” as is customary.

Things felt largely like the before times: the almost tangible fervor, the gregarious excitement, the familiarity among those who haven’t yet met in person, who recognize each other only by their profile pics. More than that, a visceral sense of gratitude emerged, surprising in its intensity. Unadulterated, amplified gratitude saturated the atmosphere from both sides of the stage. Genuine thanks for coming out, for showing up, perhaps for simply being alive, with grins on our faces and breath in our lungs.

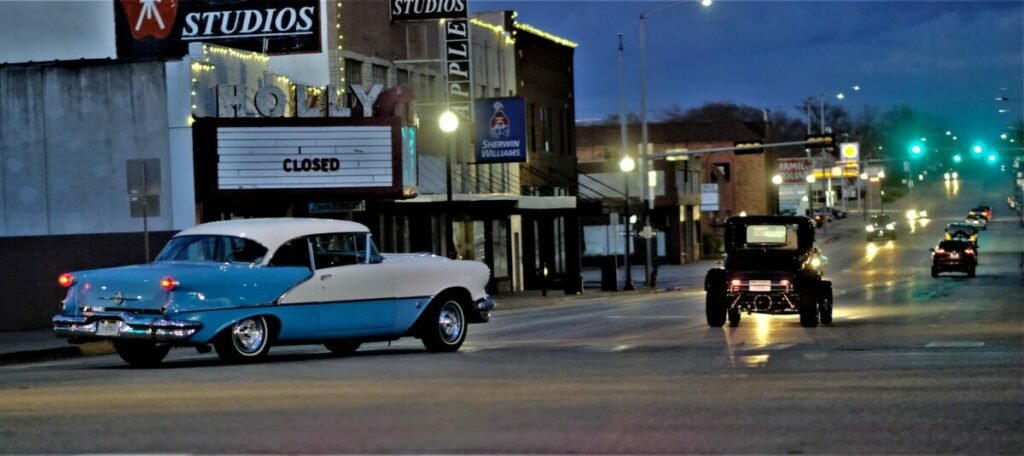

At the end of the show, Greg sang part of that Smiths song about driving around, drinking up the life of night, however bleak. I could have sworn I saw him on the verge of tears as he talked about being alone during the pandemic, at times questioning whether we’d be together again, doing this thing we love like we love nothing else. Then again, maybe it was only the glint building in my own eyes.

We’ve suffered a collective trauma, witnessed firsthand the sacrilege of biology, of humankind’s disdain for science. Our insides have been exposed, for better or worse, and we’re laid bare in the face of it. Venturing out to see my band again, returning to the thick of life, made a strange peace with it all. We were bringing each other back. Back to life. Back to civilization. I didn’t think an Afghan Whigs show could mean more to me than it already did, but now it does. Because now we know what it’s like to lose it.

Sadly, we didn’t all escape unscathed after those first shows in the spring. Numerous fans and some of the band contracted COVID, causing them to cancel the last few dates of the season and proving that the world isn’t back to normal. But everyone survived, by the grace of vaccines and science and whatever else up there shows us mercy, and the fall shows went on as planned. And for another few nights, normal came close.

The entire tour just ended, and though I’m already missing life as a forty-something groupie, I know the post-show pall will subside, and things will settle back into their regular flow. My brain will make the transition from anticipation to memory, and I’ll revel in the sustenance and inspiration I’ve received over the past several months. I’ll wrap myself in the music and keep in touch with my kindred spirits online as we anticipate the next call.

Until then, I’ll carry the ecstasy I encounter when the music enters my ears and permeates every atom of my body, first as a heady fire and then moderating, condensing into enchanted embers, never fully extinguished, waiting to be reignited.

Share this post with your friends.

This is an amazing piece of writing! What a intensely thoughtful moment focusing on community during the pandemic when we couldn’t connect. Well done!