Suddenly Emery stopped walking. He just stood there, a still-life in the afternoon, on a busy sidewalk. The crowd parted around him—one businessman swore into his cellphone as he sidestepped past.

The sun burned between buildings, a theater and a bank. Broken glass, trodden into pebbles on the concrete sidewalk, reflected brightly. Someone tossed a coin Emery lost in the sunlight. The ring when it hit the ground revealed it to be a bottle cap. Emery touched his mostly gray swirl of beard and sat down on the sidewalk, his back against the brick facade. He closed his eyes, and he turned his dirty face to the sun to warm.

From the stream of people walking past, one turned his head, lit up when he saw Emery. A blue-haired teen-aged girl walking with her friends yelped when he shouted.

“Is it Sunday already?”

Emery’s eyes drifted open. His dried lips smiled when he saw the man approach him. He knew that moon-faced man anywhere. The man wore a ratty pin striped suit that looked like it hadn’t been taken off in years. It was probably a nice suit when he first put it on. Probably fit too, the way it bagged off him like a blanket. Emery pulled a pint of 5 O’clock from his pocket, unscrewed, swigged, and offered it to the man who now knelt in front of him on the sidewalk, on the crushed glass. The man took a pull, winced, and handed it back.

“That’s tough stuff,” he said. “It is Sunday, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” Emery dropped his eyelids like soft window shades. A priest walked by with his white collar on. He looked at them, and crossed himself. The moon-faced man grinned half a mouthful of dark teeth as Emery raised his hairy chin up toward the sun, above the man’s head. They looked like two monks on the sidewalk.

Moon-face dug in his pocket, withdrew something he fiddled with both hands. Emery felt nothing but the warmth of the sun and the liquor as the man unfolded a straight razor. He tested the blade, whittled his overgrown thumbnail. Flakes came off easily. He steadied himself on one knee and reached for Emery’s face with the free hand. Even at the man’s touch Emery remained silent, unmoved. The man raised the knife to Emery’s face, held it there, midair. His hand shook, slightly. After a long moment, the man began to shave Emery’s beard. He steadied his arm with his free hand, poking out his tongue in concentration. He started around Emery’s lips and worked outward, one tiny motion at a time.

The man gave a sharp inhale when he nicked the skin just beneath Emery’s nostril. Emery flinched, but said nothing. A trickle of blood came down. The cut felt hot and itched. Emery raised his forearm, and dragged the ruddy flannel sleeve across his face. The blood smeared, and continued to trickle. Moon-face took another pull off the bottle, and regarded the label a moment.

“Hang tight,” he tucked his thumbnail under the corner of the label, and tore a small piece off. He placed it on the cut with his middle finger tip. “There,” he said, and went back to work.

Without moving his head, Emery turned his eyes toward the watch peeking out from under his sleeve. His eyes were off white, almost yellow, and lined red.

“Is that the right time?” The man asked, putting his razor away.

Emery touched his clean face, avoiding the bloody piece of paper. The watch face was broken. It had stopped years ago.

“Nice work,” he said, holding his bare neck in his palm. “Thank you, John.” The clock tower above the bank across the street flashed 5:25 PM. Emery took another sip off the bottle. “Yes,” he exhaled, “we can make it if we hurry.”

“I don’t want to miss this one. They threw me in the drunk tank last week,” John said. “That’s the last bed I slept in,” he laughed with no humor.

Emery handed John the bottle. They both groaned to their feet, knees popping. “What do you do in the winter?” John asked.

“I don’t know,” Emery said. “I haven’t figured that out yet.” He listened to their rapid footsteps, the worn flat soles slapping the concrete. They were headed toward the railroad tracks that ran down along the waterfront.

“Maybe a sleeping bag,” John said. “I kept mine. My sleeping bag. And my gun. Honorable discharge.”

Emery said nothing. Just walked, suddenly lost thinking about the life he’d lost. And who he’d lost along with it. Her name was Linda. When she’d gone, he gave up. Just like that.

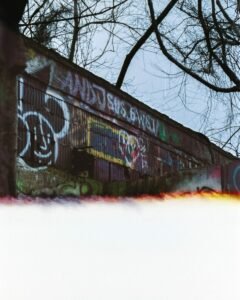

The sound of footsteps quickened. They passed the train-yard where the old boxcars sat fading in the seasons. The word “Aware” was scrawled in big devilish red letters across one.

“I wrote a poem once,” Emery said. He thumbed the folded newspaper clipping in his pocket. It had yellowed in the years it had been in his pocket. “They published it in the paper.”

“Honorable discharge. Long time ago. I wore this suit home,” John said. “Won it in a bet.”

They passed the old union station, and followed the tracks north to where the woods thickened. John stopped to spit in a bucket nailed into a maple tree. He took a drink, chuckling to himself. Their steps crunched on the rocks in between uneven sleepers. John kicked a loose spike that clattered. It sounded like dice rolling on a board to him. Emery stooped, and set a penny on the track.

“Old habit,” he shrugged when John looked at him. John shook his head.

They came to a clearing where some trees had been cut. There was some rusted metal showing, half buried. Maybe car parts. A rubber tire the grass had grown through the center of sat nearby. Several sections of stumps lay on their sides just off the track. Emery sat on one, and looked at his broken watch. John sat on another, and took another pull from the bottle. He passed what was left of it to Emery.

“Linda,” Emery said, “used to have this old map she’d draw on. It was full of roads that weren’t there, places that didn’t exist, lakes that were never there, constellations you never heard of, people she never knew.”

As Emery spoke, there was a quiet but growing rumble in the distance. He put his hand on the track and felt the motion of the oncoming train.

“You’re drunk,” John snatched the bottle back. “Shut up and enjoy the show, will you?”

“She said it was a map of her mind.”

John up-ended the last of the bottle, and threw it at the track. The glass shattered. It looked like a small wave breaking. He thumbed the razor in his pocket.

“Don’t talk to me about women,” he said, slurring.

The front of the engine rumbled into view. It was a long freighter—smoke billowed overhead, the cow catcher swallowed the track. Maple branches swayed in the wind. The engine neared the two men. When their ears adjusted, the sound wasn’t as loud as it seemed as it came on. A vast, steady lull. It was almost comforting.

The first boxcar passed, its side covered from top to bottom in wild paint. “I don’t want to hear about women.”

John held the razor in his hand.

Emery’s eyes widened, fixed on the painted boxcars floating by. What he found there in the wild graffiti that covered each stunned him. Works of art. Picasso painted the first, followed by Chagall, Munch, Beckmann. A traveling gallery.

“Can you believe that?” Emery whispered as Van Gogh floated by.

“Don’t talk to me about women,” John folded the razor open. His hand was steady.

Share this post with your friends.