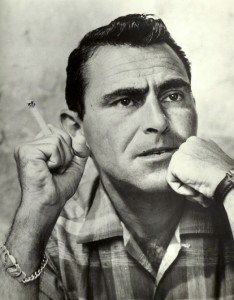

A couple of weeks ago I discovered the original “Twilight Zone” series was available on Netflix Instant. Needless to say I have (happily) surrendered hours of my life re-watching this classic series, which I still believe is one of the very few truly great things to have aired on television. (“The Muppet Show” is probably a close second.) The far-reaching influence of the show is undeniable. The twists and bitter ironies for which the show was famous have informed dozens of tropes in film and popular culture (including fiction). A quick survey of the first season, which aired in 1959, reveals the thematic architecture that underpins any number of other works considered influential in their own time, from Nightmare on Elm Street and Fight Club to Planet of the Apes (which creator Rod Serling also wrote) and Inception.

There have been other entertainments and well-acted dramas on TV, to be sure. “The Sopranos” was riveting and showed us that TV could aspire to a higher standard of writing and cinematography. And I’m sure people talk about “Mad Men” at work on Monday much as people must have done with other highly-watched shows like “Dallas.” And I’m just as intrigued by the slow-burn intensity of “The Killing” as others. But the shelf life of any discussion about TV only lasts until the next week’s show.

We find ourselves in the middle of a resurgence in long-running stories in TV shows, movies, and books. And TV shows and movies inspired by books. The cynical argument is that these products are commercial power-plays, that both TV execs and publishing big-wigs have a vested interest in keeping an audience hooked as long as possible. There is, no doubt, some truth to that. But I’m willing to concede there is a place for sagas. C.S. Lewis and Tolkien’s works were around for decades before Harry Potter or A Song of Fire and Ice.

However, amidst such epics I come to the defense of the short story. In this context, “The Twilight Zone” was television’s answer to the short story. The thing that sets the show apart from contemporary television is its discontinuity. There is the shock and satisfaction of the “aha!” moment, but then there is something that lingers in the mind. Each episode was a self-contained universe, with its own rules and characters, and people tuned in every week to watch the creation of a new world. Serling and his fellow writers only had twenty-five minutes. They gave viewers enough to intuit most of the rules, but there were also intentional gaps in logic, and things left unsaid, and that mystery only enhanced the show’s allure. (It’s interesting to note that in its fourth season, the show changed to an hour-long format, which proved less popular. Perhaps much like the long story sometimes feels too short to be as satisfying as a novel and too long to captivate like the short story? In any case, the show reverted to its original half-hour format in the fifth season.)

In this age of shortened attention spans it may seem counterintuitive to argue for the short burst of storytelling. But in some way, the short story demands more attention and focus. There is less room for error or digression. And the best short stories, of course, don’t simply end. The characters stay a while in your mind. The plot continues to unfold longer after the last period. Until one day you may return to read the story again and find yet another buried inside.

-George Kamide, Fiction Editor

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.