Two years ago I couldn’t have even told you that Carson McCullers was female. My familiarity with Southern Gothic was that limited. But this summer I found myself haunting Columbus, Georgia, her birthplace, seeking some sort of connection with the woman who wrote The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.

Like Mick Kelly or Jake Blount, peripatetic characters from that book who wandered the streets of what is only a thinly-veiled Columbus, I walked the city, past the old cotton mills along the Chattahoochee, down by the old bus station from which Antonapoulos, “the obese and dreamy Greek,” was sent off to an institution causing heartbreak for the only person who truly loved him, the mute John Singer.

In The Member of the Wedding, McCullers returns to the same streets with her main character, Frankie Addams. Frankie, or F. Jasmine as she fancies herself, is a discontented preteen in search of a place in the world, convinced that when her brother marries the next day she will leave this town. But like all of her characters, she falls short of finding home.

McCullers, whose best work came at a very early age in the decade of the 1940s, once wrote in Vogue magazine that “it is a curious emotion, this certain homesickness I have in mind. With Americans, it is a national trait, as native to us as the rollercoaster or the jukebox. It is no simple longing for the home town or country of our birth. The emotion is Janus-faced: we are torn between a nostalgia for the familiar and an urge for the foreign and strange. As often as not, we are homesick most for the places we have never known.” *

Carson observed and lived intensely. Her personal relationships were unstable affairs, torn by scattered longings that never seemed to bring her the fulfillment she desired. She married, divorced, and remarried the same man, James Reeves McCullers, all while struggling through infidelities (hers and his), strokes, and suicidal tendencies. Yet there was a purity to her homesickness and she remained a sucker for love.

In The Ballad of the Sad Café, she steps out of a story of an unlikely relationship between an Amazon and a hunchback (she did identify with circus freaks) to offer her most philosophical statement on love. It is, she says, “a joint experience between two persons—but the fact that it is a joint experience does not mean that it is a similar experience to the two people involved. There are the lover and the beloved, but these two come from different countries. Often the beloved is only a stimulus for all the stored-up love which has lain quiet within the lover for a long time hitherto. And somehow every lover knows this…So there is only one thing for the lover to do. He must house his love within himself as best he can; he must create for himself a whole new inward world—a world intense and strange, complete in himself.” **

So I guess I went to Columbus to stay close to that love, Carson as my beloved. And I walked the city of fountains with an eye for the home always promised, seldom glimpsed. Carson’s family house is now owned by the local university. The big front room where she put on plays with her brother and sister is there. The piano she trained on when she thought that music would be her career. Her typewriter behind glass in the bedroom. But she never considered this home after she left as a teenager. That place, I’m still looking for.

A writer and pastor on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, Joyner authored A Space for Peace in the Holy Land: Listening to Modern Israel & Palestine [Englewood, 2014],

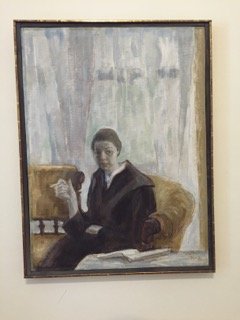

Photos by Alex Joyner

*”Look Homeward, Americans,” Vogue (December 1, 1940)

**Carson McCullers, Complete Novels, The Library of America, 2001, p. 417.

Share this post with your friends.