The woman walking into the lobby wore a brown skirt, white tights, and a pair of clogs. Her name was Shellay—she-lay—and she had a Polish last name that was hard to pronounce. She said she was a librarian and had a nerdy, unkempt look about her: Stringy hair that was dry on the ends, a pasty complexion, and a long thin nose. She wore glasses, of course. All librarians should wear glasses. Hers were a pale shade of rose. She wasn’t from Ohio, as Darcy was guessing, but from Oregon.

“I’d like to stay in the Joplin room,” the woman said. She was younger than she’d looked from behind the lobby’s front window. Her license said she was twenty-nine.

“Sorry,” Darcy told her. “It’s taken.”

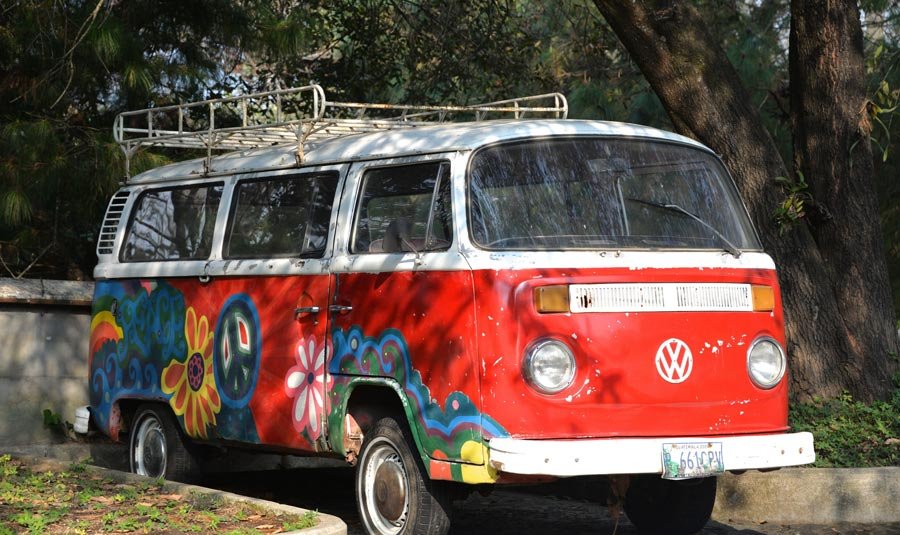

The room where Janis Joplin had been found dead was almost always occupied. Right now it was filled with three hippies who’d driven over from Las Vegas. They’d arrived in Hollywood a few hours ago in a beat-up van with a Ralph Nader bumper sticker, smelling like campfire and B.O. There was a dog with them, a sleek shepherd mix. They had come in with questions about the outdoor water spigot and where to find a convenience store. They were outside on the patch of lawn at that moment, throwing around a neon Frisbee.

“What about tomorrow night?”

Darcy checked the spreadsheet. The Joplin room was available, but she hesitated because Shellay seemed too interested in staying in it. “We have better rooms. You can stay right next door in room two hundred. There’s a refrigerator in that one.” They guarded the Joplin room carefully because it attracted weirdos. Everything was bolted down to prevent thieving, and there were security cameras in the hallway corners. The new manager had installed them after someone spray-painted Janis lives on the walls.

“I came here to be in Janis Joplin’s room. I mean – I didn’t travel for that reason, but that’s why I came to this particular motel.”

“It’s fifty dollars more than any other one,” Darcy said.

“Well, that’s OK. I want to anyway.” The librarian rubbed her forehead. “I might write an article about it.”

Darcy made the reservation and watched from the window in the motel’s kitchen as Shellay pulled her car around and got out. Her Toyota’s tires were muddy and the windshield was clean only where the wipers made contact. She pulled out a suitcase with one hand and used the other to keep her skirt from blowing up. At the other end of the parking lot sat Lord Byron, a panhandler who always managed to keep his dark beard perfectly trimmed. He made a beeline to the arriving guest.

“Christ,” Darcy said, and went out to get rid of him.

But when she got outside, she found Shellay talking intently to the man. She listened to Lord Byron’s responses: Don’t know him . . . what’s his name again? . . . I’ll keep an eye out . . . Well, I can find out for you.

***

The next day was Tuesday and afternoon business was slow. Darcy brewed coffee for the lobby and sat on the swivel stool. Out on the street, the cars honked and inched along in a polluted parade. Squinting, she could read the scrolling message on the billboard built into the hills: Heaven is open, it said in lighted lettering. Make your appointment at New Faith Church this Sunday. Heaven is open. Make your appointment at New Faith Church this Sunday. And again, and again and again. Had anyone ever followed the suggestion and made an appointment at New Faith Church? Probably not.

She checked the hippies out at eleven, locking the key to the Joplin room into the tiny metal safe where it was kept. Parked outside, the door to their van was open and the dog was lying on a carpeted bench built into the backseat. There were little curtains tied around the windows, and the stereo was booming out a Nirvana song. Their group had taken on a few new members, and one was a guy she knew. He was named Curt and he’d been a year ahead of her in high school.

“You want to come with us?” Curt asked. In high school, she’d thought of him as the quiet type, boring. Darcy remembered a Dilbert book he’d brought in during their one class together—wood shop. She’d read the book while he sawed a plank in half and drilled holes for her. “We’re heading to pick lemons out around Santa Cruz, taking our time. Driving up the coast and camping on the beach.”

“Thanks,” she said. “But I have to work.”

Curt was the last of the group to leave the lobby, pausing to catch her eye through the glass after the door closed. Lemon groves probably smelled pretty good, Darcy thought. She might have changed her mind and gone with them, but she couldn’t leave because her parents had taken all of her stuff to Phoenix. She was supposed to join them there, but she’d been ripped off a few weeks ago when some asshole broke in and stole her wallet. Now she needed a new ID, which was harder than it should have been because no one could remember the name of the hospital where she’d had been born. Her birth certificate was lost in all the moving boxes. Her mom claimed to be looking for it, but there hadn’t been any news in a while. Darcy was wondering if it existed at all — she had never seen it. She didn’t have a social security number, either, and had always used her mom’s.

The Toyota returned a few hours later and Shellay stepped out in the same clothes from the day before. There was a big dirty spot near the ankle of her white tights and her corduroy skirt was limp. She was sweating through the acrylic sweater. In the lobby, she paused near the rack of tourism pamphlets, pulling out and reading one of them carefully. Then she turned around and stepped back in alarm when she saw Darcy.

“You surprised me,” she said.

“I’ve been here the whole time.”

“OK, maybe.” Shellay set her purse onto the desk and pulled out a skinny note pad. “Anyway, I’m glad you’re here. I’d like to interview you.” Flipping through the pages, she found a blank one and clicked the tip of an ink pen. Her purse was stuffed full of things. There was a wallet made of burgundy leather and a crinkled-up paper bag inside.

“Is this an interview for your article?”

“No, not for that. I’m looking around for my twin brother. The last postcard I got from him came from this motel. He hasn’t answered his phone or made contact in a long time. I was just out looking for him and –” Shellay stopped. “I have no idea at all where he is.” The coffee pot beeped and turned itself off. “Our mom died and he’s got some money coming. I would have come sooner, but I couldn’t get off work. Then we had a big rain and the roof fell into the children’s section, so they gave us the week off.”

They went to the room together, pulling Shellay’s suitcases and chatting about her missing brother and the serendipitous rainstorm. “My cousin wanted to go to Vancouver,” Shellay said. “But I’m about to move into a new place and this one week is my chance to see Eddie again before I get tied up. He’s my twin.”

The Joplin room smelled like chemical cleaner and new carpet. The housekeepers had already been in, so the bed was made and the mirrors were clear. It was a fine and ordinary room. The new manager had even replaced the old brown bureau with a new white one. There wasn’t anything in the room that had been there when Janis Joplin had overdosed. Nothing at all. But that didn’t stop her fans from doing crazy shit. Last month, some girl used white tape to trace a dead body shape, like in a crime drama, and had her boyfriend take pictures of her lying in it. They’d shown the Polaroids to Darcy.

Shellay dropped a thick book on the nightstand and sat on the bed. Absorbed in the aura of the room, she seemed to have forgotten all about the interview.

Darcy conducted the required inspection, checking under the bureau and in the bathtub. Under the bed, she found a forgotten cell phone and charger plugged into an electrical outlet – the hippies might be back for that – and tucked it into her jeans pocket. Then she offered to check the spreadsheet to see if Shellay’s missing brother had ever been a guest.

“His name is Steven Edward Borzyszkowy,” Shellay said. “His last address was 902 West Palmetto.” She wrote the name and address on a piece of stationery paper and handed it over.

“Does he have a nickname?” Darcy asked. “Around here, people use nicknames.” Besides Lord Byron, there was Fat Cat, Looser, YZ, Clover, and Buttface. The hookers had made-up real names like Shalita and Colette. It seemed like Shellay’s brother was a street dweller of some kind. An addict, probably. That was why he was missing now.

“Not that I know of. Just Eddie.”

“West Palmetto,” Darcy remarked, “that’s a bad area.” Then she realized that Shellay must have been there already. “Is that where you were today?”

The librarian nodded and motioned to her sweaty, wrinkled clothes. Under the blank white lights of the Joplin room, she was younger and prettier than in the lobby. The puffiness in her face, from crying maybe, had softened the tight line of her mouth. “I went up and down West Palmetto and East Palmetto too. The people in the apartment he’s been living in told me he left one day a few months ago. They haven’t seen him since.”

“What about the police? You could file a missing person’s report.” Darcy knew the police wouldn’t help much. In her mind, she could see Shellay standing behind a library circulation desk with clean hair, eyeglasses polished. Still, there was something that wasn’t respectable, something shaky. Darcy imagined the library’s sagging roof, the water dripping onto hundreds of colorful children’s books.

“I suppose so.”

After a moment, Shellay asked where Janis Joplin had been found.

Right about here,” Darcy said, gesturing to the area in front of the bedside table and stepping away so they could get a good look at what was just some carpeting.

Shellay smiled and waved at the air with one hand. “Sorry. You’re probably sick of hearing about Janis Joplin, aren’t you? You could even hate her by now.” She paused, taking in Darcy as a human being. “Have you worked at this place for long?”

“I grew up here.”

She told Shellay about her mother, a teen prostitute who had been taken in by a man named Cal, who was Darcy’s father. He was the former owner of the motel and another one down the street. They lived in a suite on the ninth floor for her entire life. Her parents had sold both motels a year ago and moved to a condo in Arizona so her older sister could be treated for depression at a special hospital. Darcy had stayed to finish a semester at college, but she’d dropped out. College had been hard and expensive, and she didn’t know what she wanted to do with her life. This motel job was easy and the new manager liked that she knew the ins and outs of the building and the neighborhood. He was letting her live in a nice room one story up for only one hundred a week in rent.

“But you’re too young to have been here when it happened.”

On the night that Janis Joplin had been found dead, Darcy was not even conceived. But her mother had been on the ninth floor, already pregnant with her older sister.

Shellay was impressed. “Oh,” she said, leaning forward. “So – ”

They were interrupted when the phone in Darcy’s jean pocket rang. At the other end of the line was its owner, who turned out to be the hippie girl who’d been driving the van. The group had made it all the way to Santa Barbara before realizing the phone wasn’t with them.

“I can’t get used to carrying that thing around with me everywhere,” said the girl, named Ariel. “We’ll be there in a few hours, maybe a little longer. We need to stop for gas and food first.”

During the final minutes of her shift, Darcy pulled up the spreadsheet and checked it against the piece of paper Shellay had given her. Someone named Eddie Borzyszkowy had come to the motel at the beginning of the year and stayed for three nights. The address was not 902 West Palmetto, but 16500 Broadway. Under “Time at Current Address,” he had written “moving there this week.” There was a phone number too.

The night clerk came in and Darcy traveled up the stairs to her own place. The evening was settling in with its blue-gray light and the cars sat in somber rows. Inside her room, she poured a glass of beer and went back to the railing to watch over the parking lot. The hippie van arrived and the group spilled from the back door. Curt took the sleek dog out on his leash. While the dog was squatting in the grass, he looked up and caught Darcy looking down. He waved at her and smiled. She waved back. A few minutes later, he was at the top of the steps and she invited him in.

“We’re staying on the sixth floor tonight.” Curt said. “It’s a bigger room.” The dog, Herbie, spread out at their feet. Every few minutes he would would make a little sighing sound and beat his tail against the carpet. They stared at the dog until he turned around and lay with his back facing them.

“This is a nice place you have in here,” Curt finally said. “Kind of small, though.”

“I don’t need much,” she told him. “Most of my stuff is in Arizona.” All she had at the motel were her clothes and the textbooks she’d bought for school. They were useless now. She also had a pair of roller blades, a yoga mat, and a laptop computer.

He filled her in on some people they knew from high school and explained why he’d hooked up with the hippies. “Ariel’s cousin runs a big farm in Watsonville. We can pick lemons and live in the cabins all summer. You can make a few thousand. I’m thinking about heading to Sam Francisco after that.” He was thinking about joining the Coast Guard but wasn’t sure yet. “It’s the military and I’m a pacifist. But I love being on the water.”

They drank more and Darcy told him about how she’d found Shellay’s brother in the spreadsheet.

“Awesome,” Curt said, pleased in an innocent kind of way that made Darcy like him. “Did she find him yet?”

“No, she doesn’t even know.” Darcy patted the square of paper that had his address on it. “I have to give it to her.”

“Let’s do it now.”

They locked up Darcy’s room and went downstairs, but Shellay didn’t answer. “Hold on. I want to see something.” Darcy slipped her master key into the lock and turned on the light, crossing to lift a framed portrait from the dresser. She’d seen Shellay place it there when they’d brought in the suitcases. The portrait was of a little boy, a school picture. His light brown hair was cut choppy across the forehead and shaggy at the sides. His smile was slightly crooked below periwinkle eyes. Darcy was sure it was Eddie Borzyszkowy. Probably Shellay was out at this moment looking for him, seeing this child’s face in every addict on Palmetto.

Darcy put the portrait back on the dresser and turned to face Curt, who moved close to her. He kissed her so hard that her lips burned. The air conditioner blasted on with a pressurized hum as they fell onto the bed. He kissed her throat and breastbone, taking off her T-shirt and jeans like they were treasures. She closed her eyes and let him make love to her on top of the scratchy bedspread. She had heard of other people having sex on this bed many times. Now she was the one doing it. Life marched on. The tendons in her inner thighs trembled.

She told him about the problems she was having with her birth certificate and social security number. About how her mother didn’t seem to be looking for it, and how she was trapped at the motel and couldn’t leave.

“Maybe you should just become someone else,” Curt suggested. “You could be Paula someone. You look like a Paula.”

“I’ve thought about it. But you have to be someone before you can become someone else. You can’t do anything without an ID. I wouldn’t even be able to rent a room at this motel without a license. We make a copy of it and make everyone give a social security number, too. And I hate the name Paula.” An idea bloomed as she spoke, and she stopped herself from saying anything else.

“Come with us tomorrow,” he coaxed. “You won’t need a social security number to work at the farm.”

The dog was at the door whining, so Curt got dressed and took him out while Darcy washed herself in the bathroom. She opened the vanity mirror to see if there was a little bar of soap, but instead she found a stash of heroin and three clean hypodermic needles still wrapped in a paper bag.

It took her a few minutes to work it out. Backtracking, she remembered Shellay on the bed, rumpled and red-eyed from her search down Palmetto. What had she been looking for besides Eddie? She also remembered the overheard conversation with Lord Byron. Is this was he was keeping an eye out for?

Darcy lifted out the sack of heroin, weighing it in her palm.

In the office, she let the night clerk take a break while she took out the photocopy of Eddie Borzyszkowy’s guest card and called the number printed on it, asking for him by name when a man answered.

“Eddie? Oh, shit,” the man said. “Eddie’s dead. Passed a few months ago.”

Darcy hung up and looked out the lobby window. There was a cop in the parking lot, running license plates. The lighted sign in the hills was flashing its message. And Lord Byron was sitting alone at the picnic table, writing something in a notebook.

Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose . . .

What she had wasn’t a royal flush, but it was probably enough to win a game.

When the cop car finally pulled out and disappeared down the street, Darcy stuffed all of the papers she needed into a file folder and joined Lord Bryon at the picnic table and asked him to help her out.

“It’ll take a few hours,” Bryon said. “Gotta find the guy.”

“Can you find him faster for an extra two hundred?”

The next day, Darcy managed the morning crowd with her usual efficiency, brewing coffee, making copies, answering questions. She was only a little nervous when Shellay arrived to check out. She was on her way back home, Darcy learned. The library would reopen in a few days and there was no more time to look for Eddie.

“If by chance you ever run into anyone who knows anything, call and let me know.”

Darcy agreed, watching as Shellay got into her car, bumped a curb, and pulled out of the parking lot. The Camry turned sharply into traffic and faded into a beige blur.

It was sad, sort of, to think of all the mysteries and unknown answers to the things people were searching for. And about all the times the solution or the answer might be within reach, but the tool or piece of information that would bring clarity just wasn’t around. How could it be that the sun kept on rising when everyone on Earth was blundering around trying to figure things out?

And that was what she would miss about this place, she thought as Curt and the rest of the hippies came in. The addicts and the beggars and prostitutes were probably more honest than anyone who claimed to have it together. Maybe Janis thought the same thing that night when her fiancé didn’t show up to hang out with her. She might have laughed at life as she held up the needle and not worried about the talk about some bad stuff that was going around.

“You ready?” Curt asked.

The van was outside with the engine running and the stereo pumping. The doors were open and she could see the dog’s fur coat glinting in the sunlight. Further up front was where they’d stored her laptop, suitcase, and yoga mat.

“I’m ready. Ready to sleep.” They’d been up all night getting everything done.

“You can sleep in the van.” Curt said.

Darcy taped her letter of resignation on the keyboard and picked up her purse. Inside was the new wallet she’d bought at Walgreens. It held a freshly printed driver’s license obtained from Bryon’s fake ID connection. There was a photo of her – smiling widely — in the upper right hand corner and a name to the right, the same as on the new social security card: “Edie Borzyszkowy.” She didn’t think the missing “d” would matter, nor would the gender switch. If anything at all was true, it was that no one cared about things that didn’t personally matter to them. That didn’t affect them. And that included a dead drug addict and his lonely drug-addict sister who was on her way back to Oregon, holding a question alive as long as it would take to kill her.

Share this post with your friends.