***John Gredler is an Honorable Mention for Streetlight’s 2018 Essay/Memoir Contest***

I now had the second floor at 3 East Third to myself, a mattress on the floor, my radio cassette player and piles of books on either side. Not much else, not even a chair. Two tall windows faced the brick wall of the neighboring building with the faded letters spelling Provenzano Lanza Funeral Home painted on it. A small garden below allowed morning light to come in and the sounds of traffic to echo constantly day and night.

The floor, old wide pine planks uneven and scarred with age. A marble mantel stood on one wall, the gas hearth defunct. The ceiling still held original plaster moldings including a large ornate corona in the center where a chandelier once hung.

During the day I went to work at the single room occupancy hotel down the block. The first big job was to clear out the back yard. It had been used as a dump for decades, piled high with various pieces of broken furniture, shattered cast iron bathtubs, rotting clothes, endless beer cans and empty green pint bottles of Night Train and Wild Irish Rose.

A smashed pigeon coop with the dried carcasses of dead birds lay in one corner. Looking up at the ten story Wyoming Building next door where there was still an active coop I wondered if this one had been blown off in a storm or maybe hurled off in some dark dispute. I half expected to find its owner underneath.

Midway out and off to one side stood a lone tree, its trunk smothered in trash, the branches struggling up, a few with green leaves. A single peach grew on it that summer.

This business with the SRO was not something I wanted to be involved with. It seemed like craziness. I could not understand why Jimmy bought it. Yet I was caught up in it and could not get out. I told myself I was staying to learn the antique business from Jimmy but it was more than that. I was hooked into it, fascinated by everything that was occurring, swept along by Jimmy’s personality and energy and by the newness and strangeness of the daily situation. As if I was now living one of the books I’d been reading.

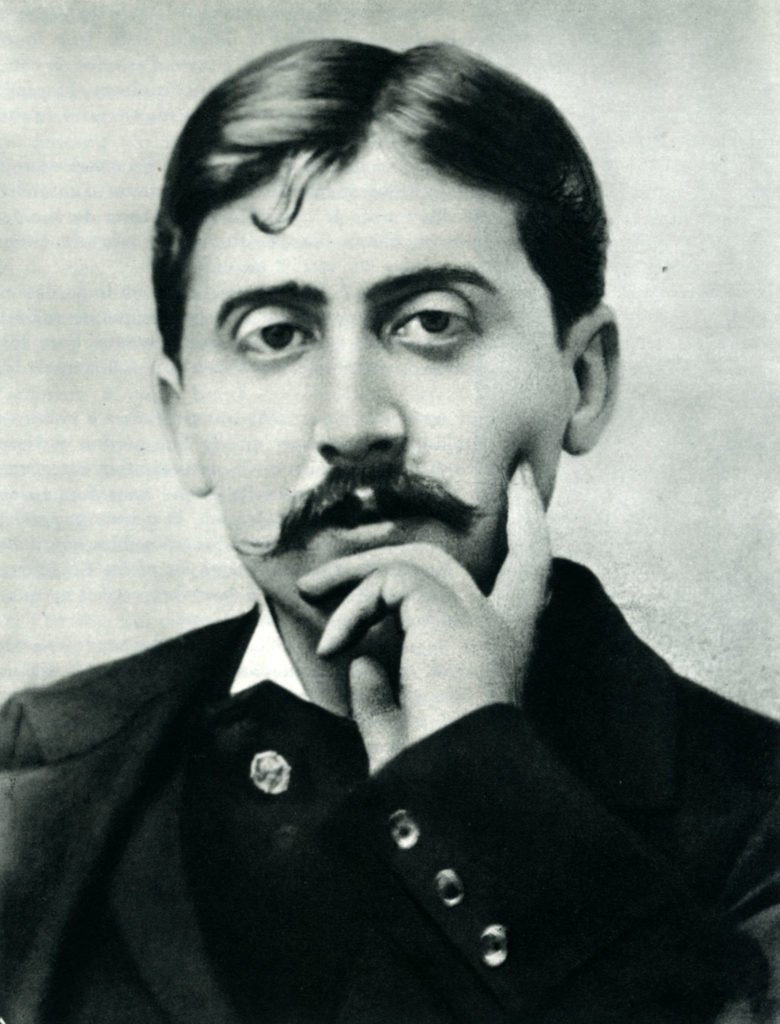

I stopped one day at a junk shop on Second Avenue and Fourth Street. There was an old two volume set of Remembrance of Things Past that I bought for a dollar. I had read Swann’s Way in college and been intrigued with Proust’s ideas of love, that one’s ideal of the beloved has little to do with who she really is.

In my room I began to read that night. It became a ritual, every morning and night I would read a few pages. It was slow going but gradually I was becoming immersed. Soon I was in thrall to those long and winding sentences.

I wrote notes in the margins, finding revelatory passages that resonated with me, that spoke of the universal. A sentence would go on and on, then there would be a passage that would stop me and make me go back, that brought all into focus. I was struck by how modern the writing was and by its fearlessness.

Repeated motifs, like the church steeple in Combray. Approaching it from afar, seeing it for the first time, its disappearing then reappearing, views and vantage making it different and yet the same each time.

The constant theme of the conundrum of love. The desire to possess the beloved, the impossibility of ever truly possessing her. Of knowing her.

All of this permeated my brain as I walked down Third Street past the drunks cadging for spare change, armed on the outside with a mask of indifference while my mind seethed with ruminations on what I had just read.

I was now cleaning and painting the small grime encrusted rooms of the SRO. Starting with the window, spraying the amber panes of glass, watching the dark yellow rivulets of nicotine tinted fluid mix with the blue Windex to form a greenish liquid that pooled on the sill, spilling over the edge and down the wall to the floor.

While we renovated the empty rooms of the twenty-nine room hotel, the old tenants wondered what was going to happen. Most were drinkers, older, all were white, the majority with Irish surnames, Callahan, Quigley, Blackburn, Wedlock. Walking into the building felt like stepping back to a place frozen in time. It was all going to change.

Reading the book was my solace, allowing me to retreat to another world. Yet also it was my education. It helped me understand the intensity and vagaries of love. About shallowness and falsity. That the rich were as petty and vindictive as anyone, perhaps more so. The pompous manipulative character Baron de Charlus preparing me for Jimmy and his cohort.

I was working there only three weeks when the first tenant died. Old Carl, who lived in a room on the first floor. He had been bedridden the entire time. Carl had a long beard and looked emaciated, but the few times I saw him alive he always nodded hello. He had cancer but did not want to go to the hospital. Mister Morgan and Ed Blackburn would help him out, getting him cigarettes and the bottle of Night Train he still managed to get down every day.

Then Morgan came to me and said Carl would not answer his door. I got his key and we opened it. I could see right away he was dead, his body stiff, his head turned up and away in an odd contortion, facing the wall. He appeared to be looking for something, or as if he was caught in a spasm of pain or of ecstasy before he died.

Morgan murmured “He’s gone” then turned to shuffle away. The sunlight coming into the room was muted by the yellowed shade. I touched him on his wrist not to see if he had a pulse but out of a morbid curiosity. His arm was like a piece of dry wood, his long nailed fingers curled in like talons. I became aware of the room’s smell, the heavy nicotine layered over the odor of Carl’s unclean body, beneath that the sharp acidic smell of urine rising up from the floor.

Later a cop came, he stood at the open doorway without going inside. “He looks dead all right,” he said before calling into the precinct on his radio. “I’ll have to stay outside the room until the coroner gets here, could be a while.”

I got a chair for the cop to sit on. It wasn’t until after 9pm that the black van marked NYC Coroner pulled up in front. Two men came in with a gurney, put Carl in a body bag and carried him out. The next day I went in to clear out his room. Under his bed were six mason jars full of urine, two without tops, in varying shades from amber to pale gold.

A month later it was Morgan who would not answer his door. He had gone into the hospital for an infection in his foot and was told he might lose it if the antibiotics didn’t work. “I’m not gonna be no peg leg”. While he was recovering he stayed in bed. I would knock on his door to ask if he needed anything from outside.

His thin pale face with a bulbous nose wore a constant doubtful expression that made me think of a cartoon character, though I could never recall which. He always insisted on tipping me a dollar or two when I came back from the bodega. Like most of the tenants when they weren’t drunk, Morgan was unfailingly courteous.

The morning he didn’t answer I got the key and opened his door to see him propped up in bed with a plastic bag over his head, tied at the neck. I stood for a moment unable to move, not comprehending. I stepped in and saw he was not breathing. A large red upside down heart covered his face, the black lettering that I knew spelled “I Love New York” crinkled and unreadable.

As I sat waiting for the police I thought to myself “This is not what I signed up for.” But what exactly was I doing here? Why did I stay, or rather why couldn’t I find it within myself to leave? I would ask this of myself many times over the ensuing years. The longer I stayed on the more difficult the possibility of leaving became.

My room was my sanctuary that first year and a half. The wood floor, the high white walls, the light pouring in from the big windows. The sounds of the traffic on Second Avenue, trucks heaving by trembling the building, the drunks always outside yelling, slurring, arguing, bottles breaking. The harsh bursts of Harleys reverberating off brick and glass from the Hells Angels headquarters down the block. Fire engines from the station house on Great Jones Street screeching and squealing. The horn of the big trucks like the bass keys of a pipe organ amplified and gone mad.

Alone on my bed, propped on pillows or leaning on my elbow, reading my Proust, all else receded. The names given to his chapters and volumes in that old translation, though the titles sounded archaic—I was drawn to them.

The suggestive Within a Budding Grove. The title The Sweet Cheat Gone verging on the absurd yet somehow just right. Cities of the Plain where he contrasts the randomness of Charlus and Jupian meeting for their hidden tryst to a bee in its gathering of nectar and fertilizing flowers. The chapters themselves: Seascape, With Frieze of Girls invoking that image of a group of girls walking or lingering, framed by sand and sea. Place Names: The Name and Place Names: The Place. The name of a place so evocative of that place, the imagining of the place more compelling than the reality of being there.

The long slowly unwinding sentences lulled like a narcotic, carrying me down a meandering stream of words only to be brought up short, to be shaken out of trance by some absolute truth.

Then back again to 3 East 3rd Street to clean and paint another room. First I’d set off two roach bombs at the same time in the small space. Later I’d go in and sweep out the scores of dead and twitching cockroaches covering the floor. The furniture would be pulled out. The old metal frame bed. The bentwood chair. The cheap wooden wardrobe. The medicine cabinet taken down from the wall.

I would wash the yellow walls, preparing them for painting, giving them two or sometimes three coats of paint. Then scrub down the floor thoroughly before applying self-stick squares over the old linoleum tiles. It was only then that the layers of odors accumulated over decades, traces of the lives lived there, were finally gone.

Share this post with your friends.