Wednesday night in Deep Ellum, the eclectic little arts neighborhood lingering in the shadow of I-45 east of Dallas’s downtown. Ever since the 19-teens when Blind Lemon Jefferson came to the barbershops and dives of Elm Street to play the blues with Lead Belly and T-Bone Walker, the area had a reputation as a collection point for artists, misfits, and the occasional spectacular violent outburst.

By August 2017, it hadn’t much changed. Pecan Lodge, a hipster barbecue joint, and the brightly-tiled Café Brazil were colonizing the neighboring streets, but the scruffy music and arts scene survived. As did the violence. Driving past a sparkling new light rail stop I noted the place where the son of one of my friends had just endured a brutal beating a few months before.

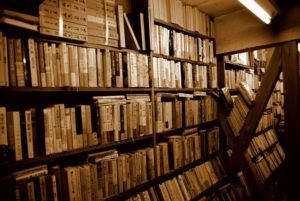

What was new for Dallas was the writing scene. The utilitarian Half-Price Books chain was morphing into a great patron of the literary arts and two new independent book stores were challenging the notion that Dallas couldn’t support a book culture that included something beyond business manuals: The Wild Detectives in Oak Cliff—coffee shop by day, bar by night, and book purveyor all the time. And the cheekily-named Deep Vellum, which was trying to establish a publishing arm out of their small shop.

Which is where I was. With Charlene, the clerk, and Ned, a young man with a shaved head and an intense gaze. And without the convener of the bi-weekly workshop—the Writer’s Bloc. “I bet he’s gotten his weeks mixed up,” Charlene said. “Let me see if I can track him down.” While she tapped on the phone she glanced warily at the nervous young man and the fifty-something guy with the three-day beard and the just-come-to-the-city look in his eyes.

I had made the two-and-a-half hour drive in from Archer City where I was holed up at the Spur Hotel for a month trying to get a book started. The first chapter was burning in my hand, waiting for its world premiere among a group of committed, experienced city writers. Such things as the Writer’s Bloc did not exist on the tailing end of the Delmarva Peninsula. Now it seemed that the audience was reduced to frantic, bug-eyed Ned, who had his own manuscript at the ready. The convener had indeed forgotten.

The shop was closing to the public. Charlene seemed hesitant to lock the door to the narrow shop with the two of us inside, but she was moving to do it when a tall, fifty-ish man cracked the door and asked, “Is it on?”

I decided to take charge. “Sure. Come on in. The leader’s not here, but you’ll make three of us.”

We each pulled a chair to the long table running down the middle of the store. Charlene retreated behind the cash register, offering us a drink as she did. Ned declined. I accepted. Joel seemed too nervous to make a decision.

“How does this work?” I asked.

“We each take turns reading our stuff and getting feedback,” Ned said, as if it were obvious.

“Well, why don’t you start, then, Joel.”

Joel drew a big hand over his long face and rattled the pages he had brought with him. “O.K.” In a precise voice, he read a poem in the first-person narrated by a beetle crawling across the tessellated tile floor of a bathroom coming into the warmth of the sunlight. It was musical and strangely beautiful. I couldn’t say I’d ever tried to put myself into a beetle’s brain, but I believed Joel had accurately captured the perspective. We talked rhythm and Kafka’s cockroach. Joel’s shoulders relaxed.

Finally he turned to Ned. “Your turn.”

Ned was primed and he handed us both a fifteen-page script he was working on. “It’s a two-person play so you both can read a part.” I flipped through the pages with their tight, single-spaced lines. To read through this would take hours.

“I don’t think we’ve got time to read all this,” Joel said.

Ned seemed a little frustrated. “O.K., well, you can read to the middle of page 5 and get the gist of it.”

Then I saw the title: The Third Philippic of the Prosecution: An Anti-Illuminist Palimpsest Based on Barruel’s Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism Volume I: The Antichristian Conspiracy. I should say at this point that my familiarity with alt-right ur-texts was not what it should be, so I didn’t immediately recognize Barruel’s Memoirs as the anti-Semitic masterpiece it evidently has become. To me it all just seemed impenetrable. Charming in it’s own way. No. Not charming. Just lunacy. No typos, though.

Joel and I did our best to stumble through the eighteenth-century turns of phrase as Voltaire and his accuser. Was Charlene smiling now behind the register? She was definitely rolling her eyes. I reached for my cup and drank deeply when the ordeal was over.

Ned offered commentary and interpretation. Joel and I asked him ridiculous questions about intelligibility and marketing, trying to avoid the bald-faced question: Who the hell is going to sit through a minute of this?

The anti-Semitic overtures were not apparent in the text, (what was?), but the more Ned explained it, the darker the project appeared, adding a layer of menace to the otherwise impregnable script. We weren’t in overt slurs here. Jews were not mentioned. But we were definitely in the terrain of grievances nursed against a vague cosmopolitan conspiracy.

Joel shifted nervously in his seat. I worked to peer beneath Ned’s earnest bluster to find the searching artist I wanted him to be. What sort of wounded soul writes such a thing…believes such things? We might have said more. But in those days before, it all seemed laughable.

It was Ned, ultimately, who asked me to read my Carson McCullers-inspired chapter on a small Virginia town. Ned wanted more philosophy in it. Joel thought the alliteration in my names was overdone. But generally, my first audience was gracious.

Charlene shuffled behind the register indicating that the hour was up. We rose and collected our papers.

“Neither of you are Jewish, are you?” Ned asked.

It was a question best not answered, but Joel ventured, “Messianic.”

“Well, that’s O.K. I can still like you.”

I winced and groaned at Ned. “Dude…”

Charlene held the door and politely ushered us back onto the street, though the lock clicked behind us with an almost audible relief that we were gone. With a purposeful stride, Ned wandered off up the street, which was only just beginning to gather shadows in the summer evening. Joel and I talked a bit longer and then I headed to the car for the long journey back to Archer City.

Three days later my old hometown, Charlottesville, ceased to be a place on the map and suddenly entered the national lexicon as an event. In 2017, there was B.C. and A.C.—Before Charlottesville and After. The text Joel and I had struggled through on Wednesday seemed less innocuous and more prescient by Saturday. This was now an America where the ridiculous could dress itself up in polo shirts and khakis, march around a statue of Thomas Jefferson, shout “Jews will not replace us!”, turn cars and flagpoles into deadly weapons, and still get presidential sanction for containing some good people.

But America had always been ridiculous and deadly—even B.C. Sometimes it finds grand expression in televised spasms of confrontation and sometimes it sits quietly around our most intimate tables struggling for words. Come to think of it, Deep Ellum is really not far from home at all.

Share this post with your friends.