At university, I lived on A Cappella Lane, which dead-ended at the railroad tracks. Elm cool, the house had ivy as a front ‘lawn’ chaperoned by a short picket fence. The landlady had a walk-in basement apartment and lived between hot-water heater and oil furnace so that her children’s rooms could be rented out.

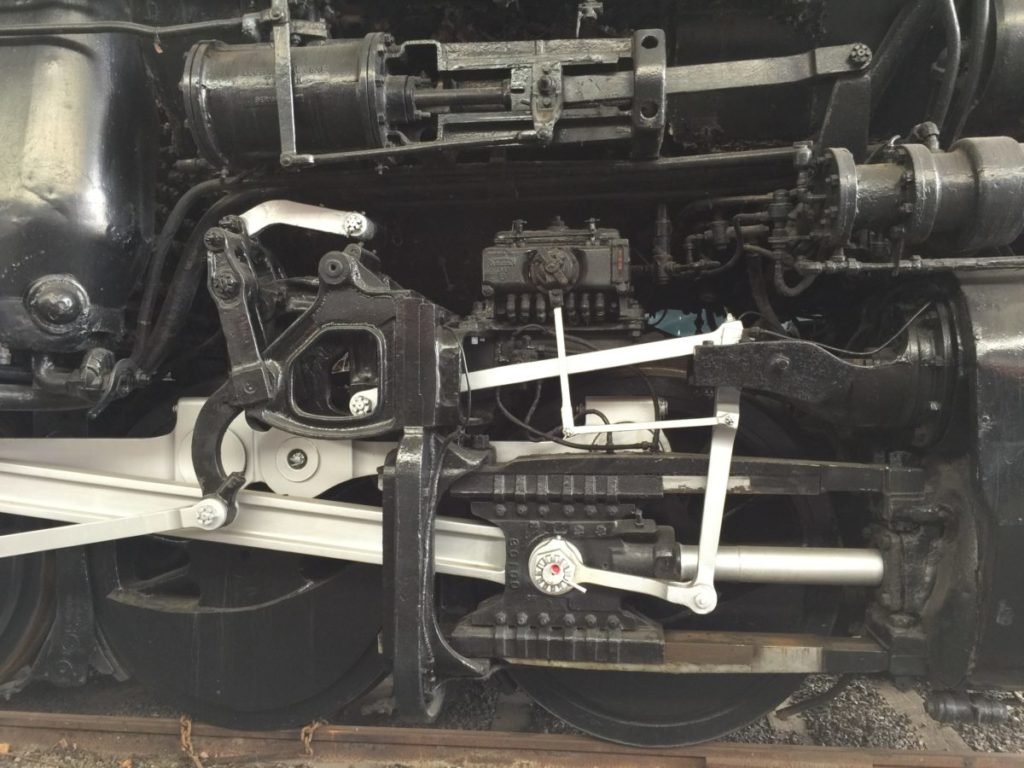

My first night the trains woke me in a nightmarish sweat, bed shaking, books falling out of alphabetical order, coat hangers chiming in the closet. Soon enough I slept unawares. On occasions thereafter I would wake in the middle of the night for no apparent reason. Not having the urge to pee, I concluded that the train was late and my inner clock was alarmed. The mind never sleeps.

A companion kitten was tolerated for a month. An art student who lived upstairs would greet me on the front porch with a provocative line about David Hockney or Frank Stella. I brought girlfriends to that room. A med student friend dropped by who, like Virgil, guided me through hangovers and the knowledge of consequences. And always there was the train outside my window. Most engines hauled countless cars of coal eastward—half of West Virginia I reckoned—to the ports of the world. Those were the days of cabooses, red, blue and yellow, that seemed to have some mystical meaning. They represented closure, a punctuation; a clarity we don’t experience anymore.

And I wrote poetry there, as painfully honest as any young poet could be. Filled with adolescent angst and romance, filled with trains and clouds and graveyards you would recognize as your hometown. I was awarded several monetary collegiate prizes and knew I wanted to write my way into life. I knew my learning disability, mild as it was by contemporary understanding, allowed me to combine words in odd ways with impunity. (My second grade teacher knew before anyone else that I was a dunce.) I fiddled with figures of speech, was serious to the bone, learned what could not be taught.

A blind girl often visited me, challenged me with parables and paradoxes. She knew how to tease as I could not, knew also the train’s ETA before I did. (She’d guess the color of the caboose eight times in ten.) I could not match her bravery and left her on the front porch for the class I dared not miss.

I have written about that place as I have about other “awe-places”: Santa Maria Novella, the Hopi village of Walpi, Winchester Cathedral, Fortune’s Cove Trail, not for some spiritual empowerment, but for the depth of survival, for the words that come to me in the middle of the night.

The freight cars that strung out the minutes were a rosary of commerce, a catalog of cargoes filigreed by aerosol artists like an endless else-to-do. I learned how to move in the passing of time. Then one February, I was damned lucky to meet Elizabeth on a blind date, a woman who sung to me in sonnets and villanelles. The chance would make any bookie blush. We remember that room on A Cappella Lane like young adults gambling all their future against those terrible odds.

That house is a trendy student over-run restaurant now. The corner pipe shop that used to sell books of artsy nudes, LP’s and a dozen tobacco blends is a jungle of clothes racks; logo tees and hoodies. Once in a while we eat at the Virginian where I used to write the poems that never made me famous.

Share this post with your friends.