Richard Key is the 1st place winner of Streetlight Magazine‘s 2020 Essay/Memoir Contest

Honeybees are swarming outside my home office under the eaves of the roofline. I would say they are hovering like tiny drones, except they probably are tiny drones. They seem very interested in a certain corner of the house. I’m afraid I’ll get stung if I investigate too much, but I know exactly what they’re up to. Six years ago we had a similar problem and called in a “bee man” who opened up that same space, vacuumed them out with a hose, and took them away somewhere. He sealed the space up, put down some kind of insecticide to discourage them, and guaranteed they would never come back. He said if they ever do come back to call him, and he would repeat the job for free. I wrote all this down in a journal because, in my jaded experience, guarantees are as rare as bee teeth.

“I got out of the bee business,” he tells me on the phone, after I spend an hour digging up his name and number from my disorganized archives. “Got to be too many regulations. The legislature passed some laws to protect the honeybee, and, well, it just got too involved. Had to get liability insurance, and that’s really what done it. Too expensive.”

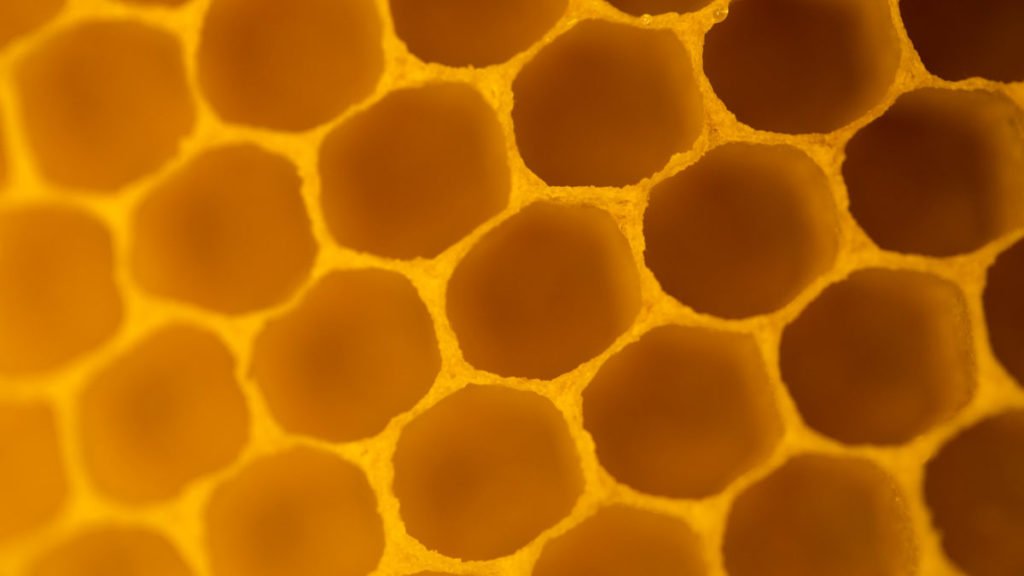

He gives me some other names to try, and I find a man who’s still in the business. He charges three times what the other guy did. I tell him about the first bee man’s guarantee. “Well, those bees leave pheromones behind,” he says. “If one of the scout bees detects that chemical, it will report back to the hive and recruit others to take a look. They’ll do whatever it takes to find a way back to where that scent is coming from. Somehow they found an opening back inside, and each bee is going in to help build the comb.” He never directly says he won’t honor the other man’s guarantee, but we both know that isn’t going to happen.

We actually had our first bee infestation something like ten years ago in a different part of the house. It became apparent when honey started dripping from the ceiling downstairs, far away from the cupboard where we keep a jar of commercial honey. It seems like some advanced bee-brain would leave a little pheromone behind telling future generations that things ultimately won’t work out here. But explorers and entrepreneurs are hard to discourage. Why do people build in the floodplain and around active volcanoes? It’s not for the peace of mind and the competitive insurance rates.

As my wife and I wait for the new bee man to arrive, I come across an article about wasps and bees in a medical journal and read aloud to her.

“It says here that the stinging apparatus of bees and wasps is really a modified ovipositor. So it’s only the females that sting. Sort of like only the female mosquito sucks blood and spreads disease.” I pause to let that sink in. “There seems to be some sort of pattern.”

“Like, only the female is capable of risking everything for the family,” she counters, “sacrificing her very life, if necessary, for the well-being of the group?”

“Yeah, something like that. Sugar and spice and everything nice.”

“What’s that?”

“Nothing.”

Bee culture is bizarre in so many ways. Somehow, certain genes can be activated to create more workers, more drones, or another queen, as needed. Drones have half the number of chromosomes the other bees have since they have no paternal input of genetic material. They have no father, in other words. Drones exist only to mate with the queen. They swarm around the queen, and if selected, they copulate in mid-flight, after which they immediately perish because their “apparatus” remains attached to the queen. But they don’t sting humans. Only the lady bees do that.

I found out a few years ago that I’m allergic to yellow jackets. The last reaction I had caused my whole arm to swell up and itch. It looked like a balloon in Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. I wrote GOODYEAR on the inside of my elbow. I’m not so wary of honeybees, but this article says systemic allergic reactions are more likely with honeybee stings than with yellow jacket stings. Africanized bees, aka killer bees, are more aggressive and tend to attack in swarms, but the venom is essentially the same as regular honeybees.

Those most maligned of insects, killer bees found themselves on the ever growing list of nature’s boogeymen. Let’s see, there’s also imported fire ants, brown marmorated stinkbugs, Formosan subterranean termites, “crazy” ants, tobacco-chewing spit beetles, and gossip-addicted June bugs. They’re in Texas. They’ve been spotted in the state next to yours. They’re headed north. There’s nothing we can do to stop them. We’re doomed.

The bee man finishes the job in a couple of hours, scraping out about forty pounds of honeycomb and related sticky mess which he puts into a garbage bag. To discourage future settlements, he sprays insecticide and insulating foam into the space and seals the wooden panel securely on the outside. For a couple of days afterwards, confused and disappointed stragglers continue to fly about trying to figure out what to do with the remainder of their destroyed lives.

The bee man says he’s worried that there might be more hive somewhere else since he didn’t identify larvae in this part, suggesting that the queen might be elsewhere—maybe Balmoral castle. So, like any decent sci-fi story, there’s a chance the menace could return. If it does, we’ll have to face it bravely, as usual, with no guarantees.

Share this post with your friends.

I enjoyed this story. I like your style. It makes me smile.

Thanks Mark! So glad you enjoyed it.

Oh, oh, oh – cannot quit laughing! Loved it!!!

Thanks Alicia. And you can keep the hornets.