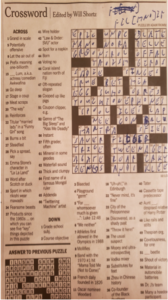

Each week, my husband completes the New York Times Sunday Magazine crossword puzzle in about thirty minutes, leaving no square unfilled. He writes in pen and never crosses anything out. Starting at 1 Across, and moving across the puzzle like a ravenous lawnmower razing grass, he completes all the Across sections to approximately 120 Across, only deigning to glance at the Down clues if he reaches a difficult patch.

If I were an insecure person, I’d feel pretty dumb by comparison. The only clues he ever asks my help with are the names of makeup product brands. I try not to take it personally.

“Here’s one you may know,” he’ll say. “What nail polish brand makes ‘Scarlett O’Hara?’”

“Essie,” I’ll say.

“Essie, huh? Are you sure?”

I flash my nails at him. “I’m not only sure. I’m wearing it.”

He squints at my nails. “Scarlett O’Hara. What a dumb name. You used to come up with nail polish names. I’m sure yours were better than that.” He’s referring to the years I spent in Manhattan advertising agencies, where in hindsight, I pulled down a good salary. Talking about money with him rarely has a positive outcome. Time to veer the conversation back on track.

“Actually, it’s a great name for a nail polish,” I say, glancing at my long, scarlet-colored nails. “And no, the names I came up with were about equal to that.”

“You can’t tell what the colors are by their names anymore,” he says like he’s ever tried.

“Well, the polish ‘After Sex’ is pretty cool.”

“What color is it?”

“It’s a deep bluish-red with a metallic sheen. It looks like a candied apple.”

“So, why don’t they just call it that?”

“I think they already have a polish called Candy Apple,” I say.

“Okay, can you please be quiet? I don’t want to get into a sidebar about nail polish. I just thought you could help me with that one clue. You’re destroying my concentration.”

Later, I study the crossword puzzle he completed. The really pathetic thing about the Sunday New York Times crossword puzzle is that even after my husband fills in every square, sometimes I still don’t get the joke. I always assumed the guys who wrote the puzzles must be white and quite elderly.

I decide to research the puzzle to see.

Will Shortz, the crossword puzzle editor, is sixty-seven years old and Joel Fagliano, the digital puzzles editor, is twenty-seven years old, but the writers of the weekly puzzles vary in age, gender, and ethnicity.

Hmmm. So, why are all the puzzles so f_ _ _ _ _ g [7-letter word obscenity] hard to complete?

My husband says I can’t solve them because I have no common knowledge. This, I confess, is true. I can tell you everything about nineteenth century America, particularly its cities. But as a kid, I wasn’t allowed to watch TV until I turned seventeen, and by then, the habit stuck. I also discovered back then that if I played music while I did my math homework, my grades plummeted from A’s to B-’s, so I stopped multi-tasking in the fifth grade. I was the original mono-tasker. If you subtract both TV shows and music from my general knowledge data base, then I guess I am dumber than the average crossword-puzzle doer.

I wonder if can get smarter, though. Not only could it improve breakfast conversation with my husband, it might stave off Alzheimer’s. At a 2017 Alzheimer’s conference in London, findings were presented from a large-scale online trial of seventeen thousand healthy people over the age of fifty. Those who completed word puzzles more often had better attention and reasoning skills than those who did not. Further, some say that word puzzles keep brains young. According to an article in Readers’ Digest: “Word puzzle fans have brains equivalent to ten years younger than their age on tests of grammatical reasoning, speed, and short-term memory accuracy.” (Claire Gillespie, The Science is in: Crosssword Puzzles Can Literally Make Your Brain Younger; https://www.rd.com/article/crossword-puzzles-can-make-you-smarter)

Wow! Puzzles are like Botox for the brain, but (hopefully) without the paralysis. I research how to solve crossword puzzles and am delighted to find this website:

https://www.nytimes.com/guides/crosswords/how-to-solve-a-crossword-puzzle

Crossword Puzzles are Stories

Here, I learn that there is a narrative structure to the weekly crossword puzzles in the New York Times, based on the degree of difficulty. The editors like to start the week on Monday with an easy puzzle. It’s a simple crossword without any jokes or mean tricks. Tuesday and Wednesday crosswords are significantly harder than Monday’s, while Thursday’s puzzle is a real brain teaser. The Thursday puzzle is as difficult as Sunday’s (though the Sunday puzzle is bigger). Friday and Saturday crosswords are strictly for aficionados.

Not only do the puzzles become progressively harder throughout the week, like novels, they have themes. A theme emerges when three or more answers relate to the same topic. Examples of themes include: anagrams, animals, circles, cocktails, colors, movies, musicals, politics, pumpkins, puns, sports teams, and (sigh) TV shows.

With themed puzzles, you may need to fill in a few clues to figure out how the theme works, but once you understand it, the theme makes answering all the remaining themed clues easier. (Friday and Saturday puzzles don’t have themes.)

Like a novel, the Sunday New York Times crossword includes a title and an author by-line. What kind of novel, you ask? To me, it’s clearly a mystery novel. You, mon ami, are Hercule Poirot [13-letter Agatha Christie detective]. You twirl your mustache and investigate, not removing your patent-leather shoes to relax until you’ve chased down all those clues.

And what would a mystery be without a few red herrings? If you crave suspense, no worries. There are plenty of clues to mislead you, until like a crossword-puzzle detective, you get to the root of them. “Professor Plum in the Conservatory with a rope!” you shout, or simply “Eureka,” if you never played the Board game, Clue, as a child. This Eureka moment is the literary climax of the puzzle.

What Makes a Puzzle Hard? It’s the Clues, Hercule, the Clues

Surprisingly, I discover that the degree of difficulty has nothing to do with answers. No. The difficulty pertains to how the clues are written. A Saturday clue for an Oreo cookie might read, “It has 12 flowers on each side,” whereas the Monday clue might say, “Cookie with crème filling.”

The article instructs me to start with the easy answers, and provides an online Mini Puzzle (5 square by 5 square) to try. Hallelujah! I complete it in about four minutes. Even better, the article encourages me not to feel guilty about looking up an answer and assures me that doing so isn’t “cheating.” (Who am I to argue with the crossword puzzle editors of the New York Times?)

I try another Mini Puzzle and complete it in about three minutes. Six Mini Puzzles later, I am late to dinner but feel the cold chicken is worth it because my IQ has ratcheted up by a few points. My husband sweetly urges me to try the Monday puzzle the following day. But I’m not sure I want to test my new crossword puzzle prowess on a Monday puzzle. For what if doing so proves what I secretly fear? That I am too dang dumb to do the Monday puzzle?

No. I will foray into this new arena one block at a time.

And She Did Puzzles Happily Ever After. Or Did She?

So, now we come to the end of my journey, mon ami. Once Monday rolls around, some of my fear subsides. I decide that if I can’t complete the puzzle, I just won’t tell my husband. There are all different kinds of intelligence, right?

And what’s a good mystery without a confession? Here’s mine. I have to look up two answers, but I fill in every square of that Monday puzzle. I have been doing the daily Mini Puzzles ever since, which also have themes and progress in difficulty throughout the week. To me, these are like serialized versions of novels—except they only take five minutes to finish.

Each puzzle has a happy ending, which is the pure joy I feel upon completion. In that one crystalline moment, I don’t think about how the pandemic has hurt New York City or who will win the presidential election or if I will ever get published again. I am at peace.

The only problem with becoming a puzzle person is that the habit can become a wee bit addictive. I’ll go back to writing my novel—just after I peek at the Sunday New York Times Spelling Bee.

Share this post with your friends.