Was I crazy to want to attend two different public events on a single hot summer’s day? Maybe, but after two years of the Covid pandemic, there were a couple of Fourth of July events I really wanted to attend.

The first was two events in one: the July Fourth Independence Day Celebration and Naturalization Ceremony at Monticello, which is the historic home of President Thomas Jefferson, located just outside of Charlottesville. And this year, I actually knew someone who was taking the oath of citizenship, a woman who goes to the same church we do.

The tradition of Independence Day at Monticello goes back to the 1920s if not earlier. (Charlottesvillian Chris Callahan recalls seeing President Harry S Truman at Monticello on July 4, 1947.) The naturalization ceremony was added in 1963. This was the sixtieth naturalization ceremony rather than the sixty-first because the 2020 ceremony was cancelled altogether. Even the 2021 ceremony, though held, did not allow a live audience to bear witness to the twenty-one immigrants who took the oath of citizenship that year. This year, more than eight hundred people watched as forty-seven immigrants became U.S. citizens.

The steps of the domed Jefferson manse were used as a podium. Hundreds of white folding chairs were arranged in square formations across the lawn and were sectioned off so that the citizens-to-be and their families were nearest to the front. I had a good spot in the front row of the section for onlookers, right behind the section for family members where, in the back row, were the husband and two children of the friend who was about to be naturalized.

Music included the Lewis & Clark Fife and Drum Corps in their red colonial-era uniforms, and soprano Christina Nicastro who sang the National Anthem. After a dramatic reading of the first part of the Declaration of Independence and a keynote speech exhorting the new citizens to embrace civic virtue, the ceremony was transformed into an open-air court session as a federal marshal called everyone to stand for U.S. District Court Judge Michael Urbanski who presided over the oath-taking.

The oath, which has been the same since Jefferson signed the Naturalization Act in 1802, requires citizens to pledge to come to the aid of their country whenever and however they might be called upon. Those reciting this oath represented every continent and twenty-two countries, from Afghanistan to the United Kingdom.

At one point, the new citizens were asked to stand if they could answer yes to such questions as, did you speak little or no English when you arrived in the United States? Did you live in a refugee camp before coming here? For the first time, I spotted the friend I had come to support when she stood in answer to the latter question.

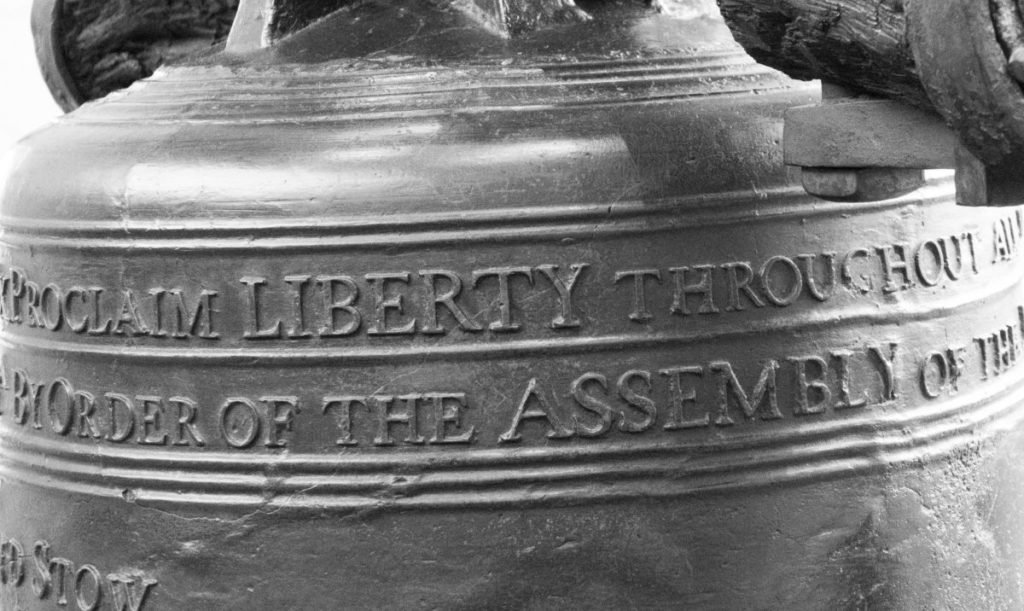

The second event, three hours later, was the ringing of Charlottesville’s Liberty Bell, located at the Ridge Street Station of the Charlottesville Fire Department. I had attended once before the pandemic. This ceremony was small and informal. The sparse ranks of the public were swelled by more than a dozen off-duty firefighters. (Until they abruptly left on a call, their engine streaking out of the lot with siren blaring.)

The original Liberty Bell is in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There are exactly fifty-five replicas, and Charlottesville has the only one in Virginia. Each replica is said to sound the same as the original—though the original cannot be rung now because of its famous crack. Every July Fourth, all the replicas are rung simultaneously at 2 pm Eastern Time, meaning that Springfield, Illinois rang its bell at 1 pm, Sacramento, California at 11 am, and in Guam they must have rung theirs before dawn. The bell rang thirteen times, once for each of the colonies that approved the Declaration.

Local celebrity Joe Thomas spoke, referring to his own remarks at the bell ceremony in 2019 about Jefferson’s anti-slavery passage in the first draft of the Declaration, removed at the insistence of the delegates from Georgia and South Carolina. This year, Thomas pointed out that the Declaration’s justification for the separation of the colonies from Britain, was persuasive enough that at least one member of the British Parliament, Edmund Burke, said, “I believe they have us.”

Because of Covid, I had not been able to go to these events for the past two years. Even though it was draining to be exposed to more sunshine (or should I say “sunburn”) than I have been all year, it was rewarding to be able to attend both of them. It was a special day.

Share this post with your friends.

The period after the “S” in Harry Truman’s name always seems to appear when the author does not put put the word “Stet” after the “S” (preferably with brackets around it). After naming their son Harry–after his maternal uncle Harrison Young–John and Martha Truman could not decide whether his middle name ought to be Shippe, which had been his paternal grandfather’s middle name, or Solomon, which had been his maternal grandfather’s first name. So they gave him a middle initial without a period to honor both grandfathers.