During my older sister’s annual visit last fall, three shoe boxes came into the house with her luggage. After the usual greetings and settling in, she opened the Florsheim boxes to reveal a postcard collection. In an effort to clean out her Tennessee Victorian, a closet shelf having collapsed the week before, she decided she didn’t want them anymore: would I be interested in them?

History is always a bit surprising, especially when close to one’s personal narrative. Imagine the archaeologist who digs up an artifact that totally alters the theory he has been working diligently to confirm. Occasionally, history just appears. Of course, Antiques Roadshow on PBS has brought such serendipity to our awareness. I want to carry the idea into our writing activity, knowing, of course, that history is not the same as fiction. Writers and poets often are prompted to write about the past in both factual and fictional modes.

Side by side on the couch, we pick through the boxes, reading messages here and there; some are cryptic without context, some squeeze in as many cliches as possible in the (generally) 2 ½ X 2 ½ inch space. Not much is very serious or compelling. My sister, having done some reconnaissance reads a few interesting notes from and to various family members, now deceased. I realize that there might be a significant amount of history here. Minor details to be sure, but isn’t history most interesting at a grass-roots level?

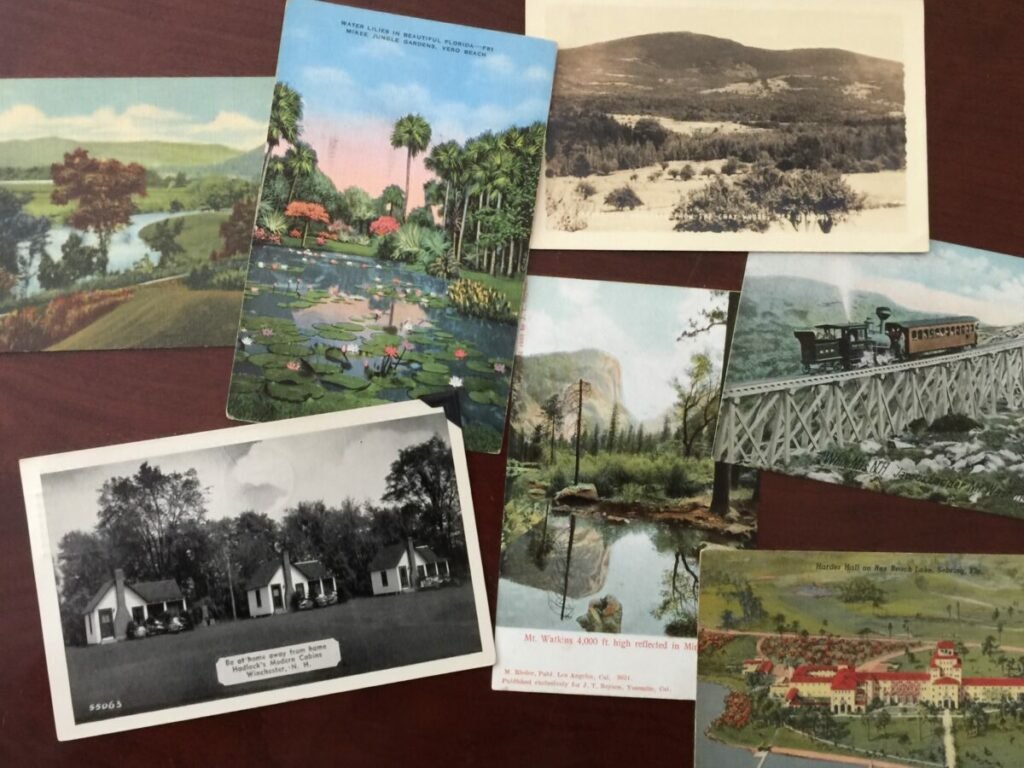

I did not know she had this collection of approximately sixteen hundred postcards, though fewer than half contain messages. As for these, the earliest is dated 1905 and comprises a group of more than forty others to the same recipient, the last being from 1909. Though not a relative, the recipient lived in the same small town as my paternal grandfather and worked with his father at Reed and Barton Silversmiths of Taunton, Massachusetts. This group is an outlier, however, as most of the cards are from the 1930s and after.

Both my mother and father were collectors and thus many of the cards were saved from their younger days—Mother’s summer camp friends earlier in the 1930s and my father’s bachelor days at the end of the decade. Dad was an organized man and had grouped the cards alphabetically by state determined by the picture side of the card. My sister had also saved cards addressed to her, making three generations of collectors.

After my sister left the collection in my care, I have learned a few details of my family. Though I knew my grandparents lived in Florida for a few years around 1940, I had never known that three of my grandfather’s brothers lived there as well. Many cards mention driving to and from New England. In another discovery, I found the addresses of boarding houses my bachelor father stayed in when he first started working for General Electric Company in 1936. I also listed the many places where my grandfather lived in the town of Taunton, Maine. He was known in the family as a restless sort, living in ten or eleven different houses.

But one of the most poignant series of cards was written by my father from places where I never knew he had been. As a GE traveling auditor he was away from my sister, who was just three and a half years old. From Oklahoma City he wrote a series of six postcards in a matter of two weeks, during February of 1945. The messages were short but the messages big: “Did you know that gasoline we put in the auto comes from the ground?” The obverse photo was of oil wells, of course. “How is my sweetheart? Can brother walk by his own self?” Another, “Isn’t this a pretty house? [Governor’s Mansion in Oklahoma City], How are all of your dollies? Do you take them for a ride on the sled when you go outdoors?” and another “Daddy doesn’t have any green stamps so he is sending this with Mother’s letter,” referring to the common, green one cent postcard stamp picturing Benjamin Franklin. He writes a few from Dallas and a year later a few from Pittsburgh indicating in one that the family was going to move there.

Post cards reflect the culture of the times in which they were produced and can be studied from multiple perspectives: the philatelic information, the evolution of printing techniques, the use of language and so on. One could study changing automobile designs, the cabin court or motel (or hotels for that matter), of road and bridge construction, of commercial architecture. (Would we think to send a picture postcard of the local Post Office?) Natural features in the landscape were/are always a popular card subject.

Ever wonder what you have forgotten in your bureau drawers, closets, attics, storage units? Think of all those subjects for writing that are there in plain sight? Do you have a collection of running shoes, the ones in which you won the local 5K? Have you saved prom dresses? Or boyfriends no longer named? Is there a set of wrenches given to you by the next-door motorcycle mechanic?

Unlike other ephemera, post cards are easily stored souvenirs. Not disparaging contemporary communication via image, emoji, video, and probably others, these communications don’t souvenir in the same way. I wonder how many cell phones (or access to cloud storage) will be inherited by grandchildren. Even so, would they have the same hands-on excitement as I have had?

There are writing ideas everywhere which is why I never understood the need for or, indeed, the popularity of writing prompts. Every small detail has a larger story. I have written about a baby-pink eraser, a dying ball-point pen, a smooth stone, a long dead chestnut tree, of hummingbirds, various tools, and more. Sometimes we forget that the meaningful world is in the details.

Share this post with your friends.