Memphis, on the brink of World War II, a crowded city, my family squeezed in a small duplex. Mother and Father work in weapons factories. We’re gathered around the radio in our tiny living room.

Suddenly a shout bursts from the curved wooden box— “Pearl Harbor has been bombed!” Three years old I hear Mother’s small scream, see my Father’s frown grow deeper. Not sure where or what Pearl Harbor might be, I’m afraid to sleep that night. I lull myself with a favorite nursery rhyme.

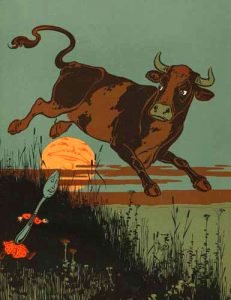

Hey diddle diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

The cow jumped over the moon.

The little dog laughed

To see such a sight

And the dish ran away with the spoon.

A child’s imagination can be a great comfort. There are so many experiences we don’t understand. I still feel happy whenever I remember this nursery rhyme. It feels familiar, a coin of great worth grown thin with use. The words live within me, a magical world all my own. I tried to make sense of events by making up stories and poems before sleep. Mother told me later I was eager to share them with whoever would listen— waiting in line for rationed meat, on a street car or in a waiting room waiting for a vaccination.

I made up poems swinging under the sycamore tree which covered most of our small dirt yard. Singing them out loud, my feet pointed to the sky, hair dragging in the dust. I felt transported by my imagination in spite of the spanking I would get when Mother had to wash my hair… again!

Then my mother proved she could perform magic when my baby brother appeared. Named Lawrence he became Sonny. I wasn’t sure what we needed him for and felt really angry when my parents started calling me Sis. Even at four I knew Sis wasn’t everything I was and insisted they call me by my own name. Then I was allowed to dress him and he became my doll baby as I pulled on his little blue clothes, tied his little blue bonnet under his chin. I found a nursery rhyme just for him which I’d sing before his nap:

Little Boy Blue, come, blow your horn!

The sheep’s in the meadow, the cows in the corn.

Where’s the little boy that looks after the sheep?

Under the haystack, fast asleep!

Love for my brother was born with the affectionate words I sang, gazing into his beautiful face.

Gifted with a scrapbook on my sixth birthday, I was thrilled with all that space for poems— vast meadows of thick paper all my own. I had, no one knew how, learned to read and now wanted to write.

Reaching school age my parents worried about sending me to public schools which were bursting at the seams. Though not religious they settled on a Catholic school. Mother and her sister, Aunt Rachel quickly crocheted the hats I must wear, sewed jumpers, the required uniform. What a strange time

I entered, leaving my baby brother at home, while I rode the streetcar to school, sometimes accompanied by a parent or babysitter, sometimes alone.

I was enchanted with chapel, especially the music. I thought God was the music. Candles flickered, shadowing the faces of living people as well as statues. I learned the figures were Mary, mother of Jesus, various saints (I always felt sorry for St. Joseph for being only the stepfather of Jesus and not really part of the family) and Jesus Himself. They were all strangers to me. One night I dreamed of Jesus and the Sacred Heart. I had it confused with Valentine’s Day. I cut out a valentine from red composition and wrote a note just for him. I don’t remember now what it said. Placing it on my bedside table, I was sure he would know it was there. In truth I thought He actually appeared in my bedroom. I was comforted by his loving and gentle spirit. Dream or imagination, this remains a vivid and warm memory.

Shy and uneasy in the class room, I was often told to sit in the corner with a dunce hat on my head. It happened with such regularity I would automatically go to the corner whenever my name was called. My “sin” was smiling in chapel. I began making an effort not to smile but the whole pageant enthralled me and I’d end up in my pointed hat staring at the wall.

Shy and uneasy in the class room, I was often told to sit in the corner with a dunce hat on my head. It happened with such regularity I would automatically go to the corner whenever my name was called. My “sin” was smiling in chapel. I began making an effort not to smile but the whole pageant enthralled me and I’d end up in my pointed hat staring at the wall.

I loved being told to “pull out your catechism.” I’d reach under my chair for the small book, sure that finally someone was giving me the lowdown on what life was really about. The words fostered my spiritual growth with their magic— the Word made flesh.

Another solace was a picture above Sister Mary Joseph’s desk. An angel called Guardian hovered over two children crossing a bridge with missing boards. Maybe I had one who followed me home every day. Now as I swung under the sycamore tree my poems were punctuated by “Father, Son and the Holy Ghost.” The swing wobbled when I’d release one hand to mime the requisite cross at head, shoulders and heart. I never fell. Maybe my Guardian was there!

When I finished first grade my parents, Aunt Rachel and her husband, Uncle Gilbert, myself and Sonny moved to a farm in Arkansas.

We all lived together in one house. Again my world changed and I didn’t know why. As an adult I speculate about their being fed up with living in a boom town created by the war or perhaps they earned enough money for the first time in their lives to buy land and a house.

So different from our small duplex, the tiny yard in Memphis, my brother and I loved the freedom of the farm. We ran barefoot through woods, caught crawfish from a pond with bacon tied to a string. We would find the little mud houses they built on the edge of the water and drop our bacon temptation in the chimney. We’d set up “crawdad” races under the chinaberry tree where the crustaceans crawled backward toward the finish line we’d designate with a stick. We had to put them back on course often as they blindly went off in many directions. Sometimes I felt I was doing the same in my new mysterious life.

Aunt Rachel would help us celebrate our “races.” Shake chocolate milk in a canning jar with ice chipped from the block kept in the ice box. A delivery man would bring a new block every few days from the town, Monticello, Arkansas which was ten miles away. Mother and Aunt Rachel would stop what they were doing and stand in their printed house dresses and flour sack aprons, hand to hip, as they listened to the news along the iceman’s route. He’d mention gold stars that appeared in living room windows along his way. I knew what that meant but couldn’t understand why families received gold stars for losing someone they loved in the war. Gold stars were for children who obeyed and did their work well.

Aunt Rachel loved cakes. Everyone thought her a genius, never using a recipe but measuring by hand. She always baked “sample cakes” along with the main one. These were for Sonny and me and we felt very important eating them. Making sure the recipe had turned out well. We also never had to wait for dessert but had our sweets at once. In winter she shook popcorn in a long-handled metal basket over fireplace flames. Always thinking of us and caring for us she made me feel safe. I thought of her as one with Jesus and Guardian but always visible and present to us.

Although rarely allowed in her bedroom I was glad whenever I caught a glimpse of the calendar she saved from my school. It made me proud that she cared for it and hung it over her bed. Mary ascending into heaven on a great roiling cloud. Somehow, in spite of the beauty, it inspired a sense of doom in me I didn’t understand. I wonder now if the invention of the atom bomb and its role in World War II were somehow presaged for me by that magnificent cloud unrolling from the earth. Maybe there had been talk about a new bomb and its magical lethal cloud among the adults.

Aunt Rachel read to me from the set of encyclopedias my family bought when I was born. There were children’s stories based on Greek and Roman mythology embedded in each volume. I knew there were powerful beings very different from us. Pan, Persephone and the girl who released troubles upon the world by opening a mysterious box. They became part of the pantheon of characters born out of my love of language— and Aunt Rachel’s love for me.

But magic was stored on that farm. Water came from the ground in a bucket that clanged against dank damp stone sides. The house was lit at night with kerosene lamps. Nights were dark, filled with the mystery of trees, the frogs that half sang, half croaked from them. Sometimes rising moons woke me with silver light. A neighbor had a car horn that played a melody he would sound when passing our farm in the evening. At least the grown-ups tried to convince me of this. But I always believed it was Pan, playing his pipes deep in the wood while I, a mortal child, must sleep.

Best of all were cows. Real cows to fill the space in which my imaginary cows had lived. There were five cows, some black and white. The cow my father taught me to milk was an old Jersey with silky tan skin and a crooked horn named Bossie. Because she sometimes grew irritable at my efforts to squeeze milk out of her teats with my small hands, Father nailed boards up the tree in whose shade I labored. A step ladder, escape hatch from the probing horn. I’d sit in the crotch of that elm until someone came to rescue me. It was a cozy perch where I daydreamed stories while I waited. Stories to write down in my “office” which was a shady place by the stream running through the pasture. With the magical thinking of childhood I felt it was MY special place to write. Grown-ups busy with the farm, a younger brother often ill, an unfinished war, I didn’t realize I was a lonely child.

Given chores to fill my time, I cleaned soot from the glass shades of kerosene lamps, feeling I was creating clear light for the coming night. But what puzzled me was being sent for the five-cow herd at milking time. It seemed short-sighted to expect cows to obey me. A small child often told to eat up so I’d grow, I dawdled over meals. Each time I went out with trepidation, heart thumping as I tracked them to the back pasture. I’d wave a stick while they milled around. Finally they’d relent and turn toward home, nonchalant, as if it were their idea all along.

Coming from the extraordinary (to me) experience of a Catholic school in a city, I was puzzled when I saw the small white country school in which I began second grade. I believed it had to hold the same number of rooms, the beautiful chapel, everything I thought to be a school. I was shocked on entering and finding only two rooms and one elderly teacher. Mrs. Vera went back and forth between the two rooms where twelve children were sorted by age. Because I was “advanced,” finishing assignments quickly, I spent a lot of time drawing. She had a box of cutouts— cows, chickens, pigs. I didn’t understand why she wanted me to trace around them when I would have preferred to read, write or draw my own ideas. But I was proud not to wear a “dunce” cap and to learn I was “advanced.”

During this time I found a poem in a magazine for women that my Aunt Rachel received in the mail. It was written by someone named William Blake and I memorized it because I loved it so much and wanted to be able to recite it at school.

Little Lamb, who made thee?

Dost though know who made thee?

Gave thee life, and bade thee feed

By stream and o’er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing, woolly, bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice?

Little Lamb, I’ll tell thee;

Little Lamb, I’ll tell thee:

He is called by thy name,

For He calls Himself a Lamb,

He is meek, and He is mild,

He became a little child.

I a child and thee a lamb,

We are called by His name,

Little Lamb, God bless thee!

Little Lamb, God bless thee.

I was fascinated by the strange language. It seemed to be speaking of Jesus and it had been a long time since anyone spoke of Him. This poem remains with me after so many years. I explored Blake as I grew older. My first child would be named for him and for an archangel— Michael Blake.

Someone found a book of children’s poetry for me. I was allowed to read from it during my “spare time” at school.

I never saw a moor,

I never saw the sea;

Yet know I how the heather looks,

And what a wave must be.I never spoke with God,

Nor visited in Heaven;

Yet certain am I of the spot

As if the chart were given.

By Emily Dickinson

Again I was drawn to the spiritual aspect as well as the language which was strange but beautiful. I read on and on, new magic to help me through my life on the farm.

A surprise better than cows arrived one day. Uncle Gilbert drove up, his truck filled with horses so wild they were kept locked in the barn until he found a buyer. As they bucked and snorted their way down the ramp I saw an animal I recognized from the Bible— a donkey with long ears and sleepy eyes. I immediately adopted him, weaving long strands of clover to throw over his ears. With my hands clasped around his neck, I’d lift my feet and swing, singing and chanting as usual. My mother screamed through the screen door, “That donkey is going to kill you!” I ignored her and continued our play as he followed me around. I can’t remember if I gave him a name. My dogs were named by me: Twinkle Toes for the small “fice” because of the sound his nails made on the linoleum inside the house. I didn’t know until I was an adult that this is an early example of “synesthesia” in my life— mixing two senses. I apparently could see the twinkle that the sound of his toes made. This is helpful to a poet.

And there was Buster Brown Cocoa Britches for a large brown dog who appeared one day at our back door. But it is lost if I named the donkey and he didn’t remain long under my tutelage, disappearing down the driveway with the still-wild horses in the same truck he came on. I had learned not to make a fuss when changes occurred. But Bottom became one of my favorite characters in Shakespeare. He has the same sweet, dumb acceptance I remember in my donkey.

One blistering hot summer day I was frightened to see my mother jerking up buckets of water, tossing them over my father and uncle who laughed and capered around the well. I learned it was V-J day, the war with Japan had ended. The men had celebrated a little too much for Mother’s taste.

A thunderstorm brewed up and we all had to run for clothes drying on the line. Many years later the storm triggered a poem that was published in a poetry magazine. It said in part: “when the radio shrills good news/ chickens blossom like chrysanthemums/ under our hurrying feet strut victory/ as we pluck laundry from a line.” This is a good example of how poetry, implanted so early in my life, continues to be a part of me.

The war ended and life changed again. We moved to town where my brother and I made friends. My Dad started his own business as a mechanic based on what he learned working on farm machinery and in the war plants. Mother worked in a dress shop “so she could buy me pretty clothes” as I became a city girl. Aunt Rachel and Uncle Gilbert joyously had their first and only child. William Patterson, called Pat who once again became “my baby.” As he grew older he wanted to know about the times before he was born. With my relish for telling stories, I tried to tell him all the magic I knew.

Although my magical childhood came to an end, magic persists for me in poetry, that of other poets and my own. For instance “a rosemary bush flames silver-blue tongues.” And “sleep falling each night/like Newton’s law.” Or a moon becomes “silver coin of happiness/slipping from my pocket.”

The sky holds “Moons, stars, planets, suns/we project language upon, brothers/spiraling heavenward, who silently bear/our myths, share the dust from which we’re born.”

And real magic still lives. If I look at the world askew or with squinched eyes I can see what might exist beyond, around or even within the more humdrum aspects of life. For me a cow will always jump over the moon, little dogs giggle from the bushes and those crazy cats fiddle away while dishes elope with their spoons.

Interview with Judy Longley

This memoir is really interesting in that it’s about a period in time and also about the creative process. Can you tell us a little about what prompted the writing for you?

Walking my dog, Wink, I found myself reciting the cow jumped over the moon and realized I was giggling. I’d been thinking about magical realism for a few days and it dawned on me that the source of it for me is this particular nursery rhyme. And I’ve not outgrown it. So I began exploring my childhood at the time I first learned it and how it “grew like Topsy” into my writing life now. That time coincided with the beginning of the war with Japan. That war became a structure to hang memories upon.

How did it feel to revisit your childhood this way?

It was fun! It became a sort of game with one memory leading to another and seeing how they fit together. Then I’d see how my current writing life evolved from them. Best of all was finding that child still vibrant and alive within me.

This piece is very much about a childhood spent during wartime— even though in a country not as much touched by the war as some. Revisiting that time, did you have a new sense of how much importance the war had on your childhood perceptions?

Had you asked me before this memoir I would have said very little. However I was born in 1938 and somehow always felt a child of WWII. It colors and shades much of my childhood. I remember my father’s shame that he was turned down for enlistment due to a scar on his lung. Saving cans for the war against Japan became a family ritual. We washed them, pulled off the labels, flattened them. I knew they would be turned into planes, tanks, etc. for the War with Japan. I saw a warship launched on the Mississippi River by the war factory my father worked in. I remember my Mother picking up the telephone and bursting into tears at the news that President Roosevelt was dead. An uncle served in the infantry in Germany. Oops, I’ve launched into another memoir!

This is also very much a piece about early spiritual apprehensions. Do you think writing it helped you see something abut your present day spirituality?

Yes. I find my current spiritual self mirrored in this essay. This surprised me. I think we are born with a capacity for spirituality. How mine was formed and continues to grow from childhood experiences became clear as I wrote. My intense passion for nature, creativity, the sense of a Higher Being, a claim on mythology and making my own seems well-founded.

What was your favorite part about revisiting these memories?

Aunt Rachel reading to me. Usually when I had earaches. She poured warm oil into my ear, warm words into my soul. And now warm memories to illuminate my childhood.

If you were going to carry this further, what direction would you take?

I’m currently thinking about an essay by Martha Collins published in the American Poetry Review, called Writing White. Growing up in the segregated South, I began to think about the effects of that on my life and those around me and the questions this brought to my childhood self. Her thesis is that if we don’t include these in our writing we are actually contributing to the racism that unfortunately continues in this country. I think she’s right.

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.

What a fabulous memoir–a joy to read, reawakening my own sense of magic 🙂