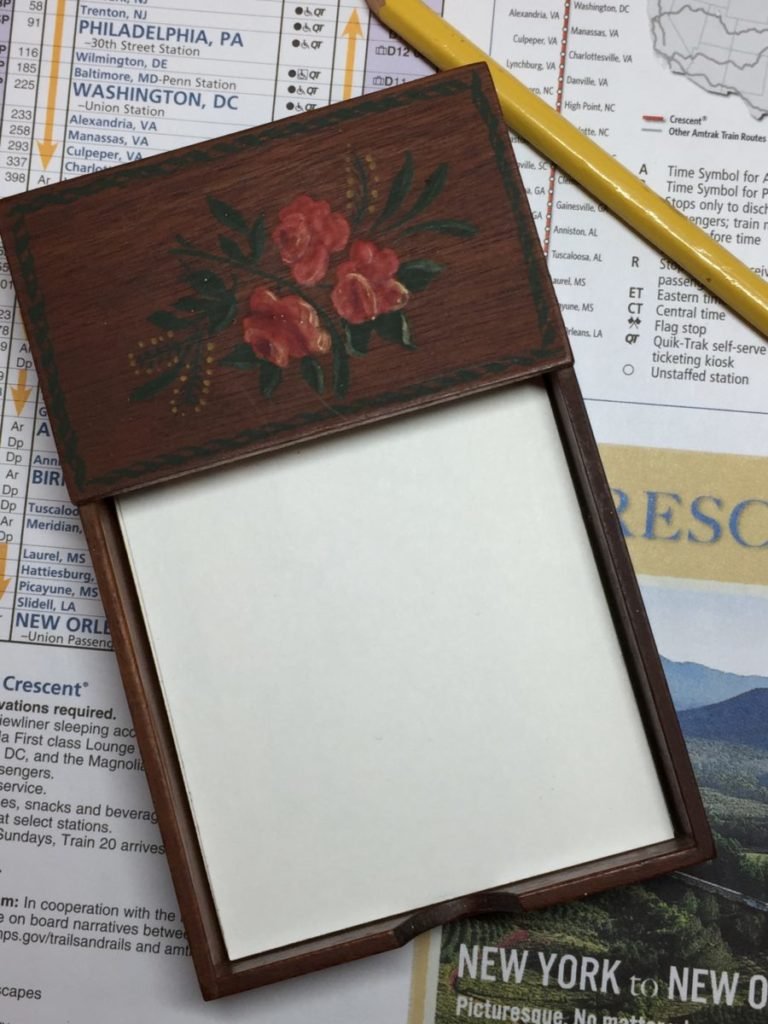

As a youngster, I watched my father slice out-of-date reports whose 8 1/2 x 11″ sheets had blank back sides; the pivoting knife of the paper cutter with its own whoosh sound, produced 3 x 5″ slips. He warned me to mind my fingers. He made a little box with half cover in his basement shop to hold the repurposed pages. My mother then painted flowers on it to marry the artistic to the practical. This box resides on my telephone table in the back hall, quaint along side our landline and answering machine. These conveniently sized slips were used to write grocery lists, record petty expenditures, to jot odd telephone numbers, to pencil reminders of one sort or another and later, for me, phrases that might sniggle into a poem. To be fair, they were used for doodles drawn during endless, and eye-rolling phone conversations, as well. This was before NGOs mailed you free mini-pocket pads, fridge magnets, or ‘personalized’ address labels for promotional purposes.

There are two kinds of lists with innumerable sub-sets: those concerning the future and those concerning the past. The planning characteristic of ‘to-do;’ Honey, (please) do, aspirational creeds like Franklin’s moral perfection project, clearly address the future. As many or more are lists which record the past; curriculum vitae, Dante’s litany of regrets and shames, or the achievements enumerated in the Guinness World Records. There are lists for just about everything: check lists, black lists, hit lists; lists of the Fortune 500, of wood screw sizes, of a store’s inventory, lists of invasive plant species . . .

There are, of course, specific kinds of lists: scales and schedules come immediately to mind. Scales are lists with some sort of continuum of value or change like the Beaufort Wind Force Scale, musical notation, measurements of physical properties such as the Richter Scale. Schedules are usually thought of in terms of time: the timetables of the Southern Crescent, tides tables, high school soccer games and calendars. Oddly, a list of window sizes for a building is called a window schedule—go figure. A college syllabus is a class schedule with some weight, and a warning to the mentally lazy, perhaps.

If you search via Google for “work schedule” you will be dumbfounded to learn that there are about twenty different ones: from the obvious “full time,” “part-time,” “fixed,” and “Flex-time,” to the more complicated “Dupont Shift,” the “Pitman Shift and the “Kelly Shift” which juggle hours, days, and weeks into a schedule which benefits business productivity. (I wonder how workers remember them and manage to show up at all.) Working by myself for years, I never thought of my woodcarving career as “freelance-time.” I lived my work, not particularly free from deadlines, cost estimates, and the striving for quality.

There are preposterous lists of course: the promises of politicians, wish lists, what-if speculations of historians, the sequence numbers of millions of Power-ball losers. One can never have too many lists. Let’s list more synonyms: index, catalog, directory, tabulation, alphabet soup, roll, docket, menu, charts . . .

I have previously written here (“The Garden Club Ladies Visit the Historical Society”, March 28, 2022) about my research of the local garden club as a civic organization. I have not mentioned, however, the factual lists required to make sense of the minutia of minutes, ‘no-date’ newspaper clippings, partial financial records and the other ephemera over the course of the first fifty years of its activity. As I read through these materials, I compiled lists of officers, list of committees (their creation and dissolution), the ebb and flow of funds, and a list of places the group explored as a suitable meeting venue. I would not know how to present the rich and varied goings-on of the club without first allocating them to categorized lists. I hope, however, that the final book doesn’t read like a list, though a table of contents may betray this desire!

My mother, when I was a bored teenager, would advise, “Make a list,” as if to do so was a sure cure. Her point, to give her credit, was that there is always something to do. Not only was this directed toward things to do, but also to how to be: always curious, always engaged, always busy. Her advice, and my New England genes, led me to the notion that one needs a disciplined, organized mind and one way to obtain that goal was through the act of making lists. To echo Ecclesiastes, to every mess (or difficulty) there is a list.

Not only do lists tend to pull ideas from the dark, but they order the world. A process akin to the adage that knowing there is a problem is half the problem solved. The mere act of listing clarifies in the same way that constellations give form to a baffling array of stars. But when lists seemingly preclude chaos, they also can stifle spontaneity and consequent serendipity. Lists only surprise when there are jarring juxtapositions, mistakes, and anomalies which lead to some insight. In a sense, the pleasure of poetry works the same way by gathering and contrasting images. The thesaurus, the dictionary, and books of literary symbols may prompt the writing of poetry. I seem to remember that Dylan Thomas, and no doubt innumerable others, jotted lists of rhymes or synonyms, phrases, etc. in the margins of their drafts.

The trick is, I suspect, to consider lists as tools; maybe not the shinning blades of a woodcarver, hooks of the crocheter, or even those ‘tools’ of a Virtual Assistant, laser engraver or 3-D printer, but as a sort of hands-on thinking. Through writing the mind remembers. Yes, one can make lists on a Smart phone, Ipad and so on, but they don’t stay in pockets as a constant reminder as does a wad of paper.

Despite the bullet points of power point presentations, contemporary information seems detached from a ‘mother list.’ Google-supplied information, the digital list of 0 and 1 robs us of context. For example, the digital clock supplies no clue as to the passing of time while the analog is a sort of circular list which strives to be in the future, but is sadly mostly in the past. At a glance, the long hand does not move and we gladly accept the illusion, knowing all the while we have more to do, the clock is ticking.

In younger days, I macho-ed through the days without such a feeble thing as a list, like neglecting to wear work gloves or obeying the speed limit, but I have come to appreciate the perpetual list of life; the need for home maintenance, the nag of birthdays, the stock market bear and bull, the accumulated ancestors.

Though there is a Sisyphean lesson here, there is a subtle joy in crossing off items of a list; a graceful, single line will do.

And such is the taxonomy of lists.

Share this post with your friends.