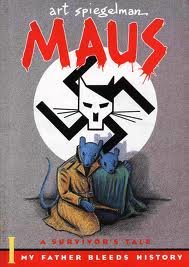

At one point in the graphic novel Maus, Art Spiegelman’ chronicle of his father’s life before WWII and in Auschwitz, and the author’s own difficulty dealing with that history, Spiegelman is speaking with his therapist, who is also an Auschwitz survivor. Spiegelman is having great difficulty writing the second part of his book, which concentrates on the father’s time in Auschwitz; the holocaust, as a subject, is too large, too complex, too evil to even address, to the point where both men are struck dumb. Eventually the therapist quotes Samuel Beckett, saying “every word is a stain upon the silence, and nothingness.” They pause for a moment in consideration, until the therapist observes, “then again, he said it.”

The question of how to address real-life horror when language seems inadequate is not a new one, and responses range, but I’d like to address just the idea of silence. An old literature professor of mine liked to assert that language was completely insufficient. His examples were that the only movie to properly evoke the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was Hiroshima mon amour, which consisted of a survivor of the bombing telling his westerner lover that, no, she could never understand what it was like there where the bomb was dropped. My professor felt the same way about the film Shoah, which consists largely of holocaust survivors stuttering inarticulately about what they endured. (He also called films like Schindler’s List pornography.)

I understand my professor’s point, but I find it deeply limited. All sorts of questions come up: is the scope of the suffering what defines an event as unaddressable? Are we allowed to write and talk about small tragedies, but may only address large ones indirectly, as my professor seemed to think was appropriate? I know his point was that words are insufficient, but it still seems limiting. It seems that directly addressing acts of evil in the world is more difficult than would be other things, but to give up on that and declare language inadequate just means you should have done better with the language.

More than that, some events are so large, that they deserve multiple points of entry and address. How do you tell the stories of those that died, except through some kind of narrative? How do you explain the overall arc of the history of that period? What if a survivor wants to tell his story narratively, on film, as did one of the producers of Schindler’s List?

Simple good taste tells us that, when dealing with certain subjects, a generous amount of tact and thoughtfulness is required. But I reject the idea that there are things too serious, too important, too heartbreaking to write about. We have to tell stories, if only to allow ourselves to deal with things too big for us to comprehend. Silence is very respectful and reverential, but it doesn’t get anything done.

-Aaron Weiner

Non-fiction Editor

Share this post with your friends.