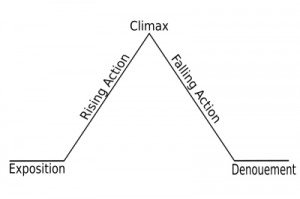

Something I’ve noticed about public discourse over the past decade or so is the habit or need to assume or force our real lives and events to fit into the arcs and tropes of fictional stories. This happens to us as individuals but also occurs in the larger communications of our culture, from the way we address the lives of individuals to how we address movements and nations. I call it narrativism, because I don’t have a better word for it. I call it narrativism in the same way that one calls bias based on skin color racism, because it can be just as dangerous.

Narrativism appears in unobtrusive forms in our lives all the time, often in the idea that something is “meant to” or “supposed to” be. When we are young and in love we say we are meant to be together. To reach our dreams we are supposed to go to a certain school, we are meant to obtain a certain career. You’ll notice these assumptions tend to drop off the more we experience real life, with its hardships and disappointments. In real life there is no certain way the world was “meant” to be; and experience teaches us that no belief in destiny, or that we are the heroes or our own stories, can deter layoffs, prevent disease, or ward off other human calamities.

Narrativism is most obvious when those who produce media for consumption attempt to fit real lives into something more easily digestible. The most apt example that comes to mind is how, every four years at the Olympics, broadcasters insist on fitting prominent athletes’ lives into the initial talent/struggle through injury/return to sport after absence/will they triumph? narrative, as if all professional athletes’ lives fit such a bland arc. But if narrativism was limited to just our personal lives and our pop culture we could live with it. But it’s not.

Part of the problem, I think, comes from the way we are taught history, whose particulars are much messier than the bowdlerized version we often first encounter as children. Washington’s military acumen and humility is emphasized in our picture-books, his slave-ownership not mentioned until middle school. And ditto with Thomas Jefferson and a number of other founding fathers. For me the inherent conflict between Manifest Destiny and the existence of American Indians wasn’t addressed in depth until high school. And I had to wait until college to get into the real complexities of reconstruction and the Jim Crow-era South. The problem being that, perhaps because of the poor first version of history we received, or because it is simply more narratively convenient, our culture has used these sanitized versions of events to color the stories we tell about them.

For example, our popular idea of World War II’s European conflict is that of a last-minute save by Americans coming in to repel the Nazis just before the clock strikes twelve for England. Compare this to the actual count of Nazis defeated, concentration camps liberated, and percentage of population lost by the Russia, and the US’s contribution suddenly seems much less significant. Yet our fictional narratives of the era paint us as the saviors. And even as it damages our view of history, it also harms ability to predict how history will proceed.a

When President Obama announced the death of Osama bin Laden it was a serious, brief event. He stood at the dais explained details to the press, and that was it. Compare that to Paul Bremer’s announcement of our capture of Saddam Hussein, with the macho declaritive “We got ‘im,” to a auditorium of cheering soldiers. (One must assume the soldiers were ordered to cheer, or at least were informed who was captured beforehand, lest Bremer make the announcement to a confused crowd. We got who?) The same goes for President Bush’s bewilderment at Iraq not instantly turning into a functioning democracy after the toppling of Hussein (there’s an often repeated anecdote that Bush, in the Oval Office and informed about yet more sectarian violence breaking out, wondered aloud why Iraq had no Founding Father-type of leaders rising up and saving the country), or Under Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz being so sure of how the war would play out that he could state the exact price the war would cost.

The origin of the United State’s still-unfolding debacle in the Middle East is overdetermined and highly complex, and I don’t wish to expand an already-long blog entry, but I believe that at least part of the mess our country is now in is due to those in power making the assumption, the blind, dull assumption, that war, perhaps the most chaotic endeavor a civilization can engage in, would go according to plan.

Aaron Weiner

Non-fiction Editor

Share this post with your friends.