The premier poetry event of this year’s Festival of the Book in Charlottesville was “Shrines to Longing,” the March 20 reading by Charles Wright, America’s current (20th) poet laureate, and Mary Szybist, who was a student in the University of Virginia’s MFA program when Wright was on its faculty. Both poets attended the Iowa Writers Workshop. Both have a distinctly Judeo-Christian flavor to their work. The 79-year-old Wright read from his 24th book of poems, Caribou, Szybist from her prize-winning second volume, Incarnadine. Although the full house at UVA’s Culbreth Theater was clearly entranced by both poets, Wright, with his hilarious, self-deprecating Southern humor, stole the show.

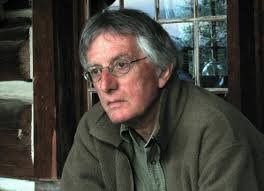

A slender, youthful-looking man, with round glasses and a shock of silver hair falling onto his forehead, Wright read the first poem of Caribou, “Across the Creek is the Other Side of the River,” in a soft, almost whispery voice:

No darkness steps out of the woods,

no angel appears.

I listen, no word, I look, no thing.

Eternity must be hiding back there, it’s done so before.

Wright stumbled over the last line of the last stanza:

And if the darkness does not appear,

that’s a long time.

And if no angel, it’s longer still.

Sitting in the third row, I heard him mumble to himself, “Even if the line wasn’t so great, there was no need to muck it up.” The line – and the poem – came through, despite Wright’s “muck-up” as a moving illustration of what the poet has identified as the three obsessions of his poetry: language, landscape, and the idea of God. Wright claims he has been looking at these three themes from changing angles all his life. His poems are understated, colloquial, mysterious and, at the same time, slyly humorous. In the poet’s waiting for the “darkness” to step out of the woods and for an “angel” to appear, and in the very sparseness of his language, the listener feels the intensity of his longing for the sacred. To hear him tell it, Wright has been waiting throughout his poetic career for the darkness and the angel to appear.

Sitting in the third row, I heard him mumble to himself, “Even if the line wasn’t so great, there was no need to muck it up.” The line – and the poem – came through, despite Wright’s “muck-up” as a moving illustration of what the poet has identified as the three obsessions of his poetry: language, landscape, and the idea of God. Wright claims he has been looking at these three themes from changing angles all his life. His poems are understated, colloquial, mysterious and, at the same time, slyly humorous. In the poet’s waiting for the “darkness” to step out of the woods and for an “angel” to appear, and in the very sparseness of his language, the listener feels the intensity of his longing for the sacred. To hear him tell it, Wright has been waiting throughout his poetic career for the darkness and the angel to appear.

Moderator Kevin McFadden kicked off the question and answer period by asking both poets who they wrote for: Who was listening? When Szybist and Wright seemed stopped by the question, McFadden suggested, “For yourself, perhaps?” Both poets rejected this notion and Wright could be heard muttering in feigned outrage, “What kind of a question is that?” Aloud he offered one of his characteristic off-the-cuff observations, “You just hope someone will read it.”

McFadden went on to question the poet about what inspires them to write a poem, For Mary Szybist, a poem begins with an idea, religious or cultural. “I like to face what has an imaginative hold on me,” she said. “I like to re-make it, push back against what I’ve inherited.” Wright, on the other hand, is no idea poet. For him, perception is the key: “I’m taken by what I look at, the natural world, which opens into the supernatural world. My poems never start with an idea. He went on to say, “All of my poems are the same poem. The three things that obsess me all inform one another. I think of them as meditating on the same theme. I’m always repeating and trying to be better on the same theme. I have meditated to the point of stillness.” Giving a twist to the traditional notion that hard work follows the initial inspiration to write a poem, Wright added, “The harder you work, the more inspired you get.”

McFadden went on to question the poet about what inspires them to write a poem, For Mary Szybist, a poem begins with an idea, religious or cultural. “I like to face what has an imaginative hold on me,” she said. “I like to re-make it, push back against what I’ve inherited.” Wright, on the other hand, is no idea poet. For him, perception is the key: “I’m taken by what I look at, the natural world, which opens into the supernatural world. My poems never start with an idea. He went on to say, “All of my poems are the same poem. The three things that obsess me all inform one another. I think of them as meditating on the same theme. I’m always repeating and trying to be better on the same theme. I have meditated to the point of stillness.” Giving a twist to the traditional notion that hard work follows the initial inspiration to write a poem, Wright added, “The harder you work, the more inspired you get.”

Wright, who has written “Less is more nothing is less,” describes his poetry as gravitating toward silence. “The true condition of poetry is prayer, and of prayer is silence,” he said. The point was echoed by Szybist, who said, “Perfect prayer is silence.”

While silence may be Charles Wright’s ultimate goal, as I read the captivating poems of Caribou, I can only be grateful he has not yet arrived there.

–Sharon Leiter, Poetry Editor

Follow us!

Share this post with your friends.