What is the difference between illustration and fine art?

Streetlight’s featured artist Kate Samworth, and Nick Clark, former Chief Curator and Founding Director of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, consider the question.

Illustration as fine art — and the relationship of children’s book illustration to “art” or “fine” art — are complex questions. In short, they are, or were, the same. Illustration, or “narrative” painting, dominated Western painting for centuries until the mid-1800s.

The longer answer requires that we decide what is the difference between “fine” and other art? And why make the distinction? Illustration and “narrative” painting both translate written stories into visual images, so the terms can be used interchangeably.

Some would say that a reproduction, such as a print, has less value than a unique painting. Would we then exclude the lithographs of Daumier, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Mary Cassatt from the “fine” art category? What about the etchings of Rembrandt, or the wood engravings of Durer? Should we exclude the woodcuts of Japanese artists that had such an enormous impact on the Impressionists, like Degas, Gauguin and Whistler?

The method of reproduction has an obvious impact on monetary value, but does it also determine cultural value? Two important writers, Walter Benjamin and John Berger, have written extensively and eloquently on this topic.

Most of us would accept Renaissance painting as “fine” art. With the exception of saints’ portraits, Renaissance paintings are illustrations. This art was created during a period when books were rare, prohibitively expensive, and few people outside of the church could read. Biblical scenes were illustrated for an audience that “read” the paintings through the language of symbolism. Painters at this time were expected to have a command of drawing, composition, and application of pigment.

In seventeenth century France, the hierarchy of Western painting was clearly defined by the Royal Academy in Paris. “History painting” was placed above all other genres in terms of cultural and monetary value. This included illustrations, or “narratives,” of historical, allegorical and mythological themes.

Pass over the various movements in painting that followed the declining power and influence of the Royal Academy and consider the impact of Duchamp’s Toilet. He brought the debate over the definition of art to the fore, where it has remained for 98 years.

After World War II, the Abstract Expressionists rejected all recognizable subject matter for fear that it would be used as propaganda. Their influence on contemporary painting cannot be overstated. While “narrative” painters still exist, there is a clear preference in the museums, art fairs, and biennials, for content-free, process oriented work.

How do we know “fine” art when we see it? Do museums show only “fine” art? Does it exist outside of museums? Critics, curators, and art buyers may influence our opinion, but they don’t agree on the standards. “Fineness” is not a measure of technical ability, but of some other quality that cannot be named.

Some insist that drawing is an essential skill, while others will argue that technique impedes the work of the subconscious. Some believe that “fine” art is the result of careful planning and meticulous control, while others hold that art should pour out of the individual “unhindered by the thought process,” as put by my painting instructor.

Contemporary painter, Auseklis Ozols, described art as a balance between technical ability, aesthetic decisions, and emotional content. In my opinion, any picture which exhibits these is “fine” art, regardless of the surface that it is painted or printed on. Illustration, whether created for children or adults, has the potential to reflect and interpret the world, to raise questions, and to re-present the familiar. Is that not, ultimately, the purpose of art?

— Kate Samworth

See more of Samworth’s art at her website katesamworth.com and in our featured art profile.

CONTINUING THE CONVERSATION…..

Artists have long mined the history of art to inform their aesthetic, and since at least the 19th century, this has been true for illustrators of children’s books. We also need to be mindful that many of greatest figures in the history of art have illustrated books—from Rubens and Rembrandt to Delacroix and Goya. In the 20th century Matisse, Picasso and David Hockney have pursued the genre.

C. S. Lewis’ insight about what constitutes an enduring book: “No book is really worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally (and often far more) worth reading at the age of fifty…” offers importance guidance for endurance. What is it about Peter Rabbit, Ferdinand, Madeline or Babar that continues to captivate the imaginations, affections, and loyalties of readers young and old? Clearly, imagination is a key ingredient. Imagination triggers invention, and invention historically has been central to the making of superior art.

This age-old idea received popular recognition in the 18th century. Sir Joshua Reynolds, in his capacity as President of Britain’s Royal Academy, delivered annual Discourses in which he repeatedly acknowledged the importance of knowing the art of the Old Masters, borrowing from them, and making something original through invention. Prior to that, in the 17th century, the French Academy codified the hierarchy of the genres in painting, and literary subjects, mythology, and history occupied the upper echelons while far down the ladder wallowed landscape and still life (nature morte—dead nature).

The advent of modernism with its emphasis on non-representation seriously affected the stature of illustration. With its attendant commitment to abstraction, modernism viewed itself as highly intellectual and relegated the representational art to the nether realms of the pedestrian.

One must keep in mind that illustration is at the service of an over-arching design and the viewer is seeing it in a second or third generation format.

Interestingly the distinguished art historian Robert Rosenblum, visiting the new Norman Rockwell Museum in the mid-1990s (to see the building designed by his friend Robert Stern), had a major revelation about the artist’s abilities upon seeing his work in the flesh. The authority of the original is a critical ingredient.

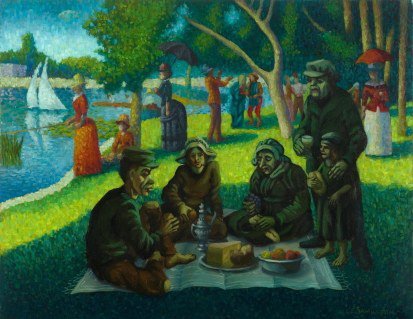

Which brings me to Kate Samworth. She clearly relishes in creating provocative and invariably humorous juxtapositions with iconic paintings in her independent art (and I call it this rather than “fine” art to blur the lines of distinction between it and illustration). Most startling is her insinuation of Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters (1885) into Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte (1884).

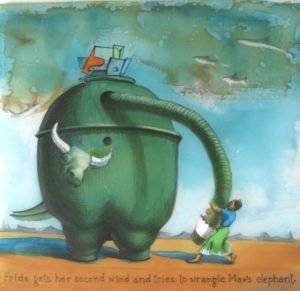

Elsewhere, Frida Kahlo visits Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles (1888) as well as capturing the “pachyderm” in Max Ernst’s Elephant Celebes (1921); this mechanical beast has some of the assembly-line aspect that figures into her first children’s book, Aviary Wonders, Inc.

She embarked on this tangent with the encouragement of the eminent children’s book artist, David Wiesner, with whom she was studying at The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and coincidentally Charles Wilson Peale’s The Artist in his Museum of 1822 in the collection figures prominently into much of her appropriation.

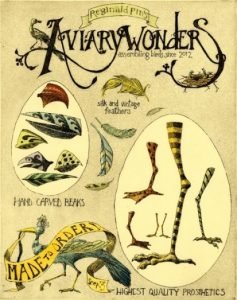

Aviary Wonders, Inc. is a bittersweet treatment of extinction. Motivated by her own passion for bird-watching and hearing a piece on the radio about a family returning to New Orleans post-Katrina and noting the absence of birds and the attendant silence.

Her message is delivered with a velvet glove in the guise of a wonderfully wacky DIY catalogue to enable the interested person to replace extinct birds according to their personal preference—again a commentary on the quest for the customization of the contemporary shopper). Even here she cannot refrain from connecting to the tradition of Fine Art—her palette choices include the Old Masters, the Impressionists, and the Minimalists.

As one works through the “parts” catalogue (and I cannot help but think of Elizabeth Butterworth’s magnificent suite of Macaws [1993] where separate elements accompany the full figured specimen), the reader encounters images punctuated by poignant reminders of birds that no longer exist.

The “Style Gallery” at the end is a visual banquet of tongue-in-cheek. The “Rockefeller” collar nails it, and the crests, wattles, and combs are laugh-out-loud riots of color and wit, as Samworth truly hits her stride. Her techniques is sound, her visual vocabulary is extensive, and her sense of humor is boundless (And I do hope she knows Quentin Blake’s Cockatoos [1992]). She has a bright future.

— Nick Clark

A founding director of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, MA., Clark was formerly chair of education at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, as well as Curator of American Art at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, VA. At the Chrysler Museum, Clark organized an exhibition with Michael Patrick Hearn — a leading scholar in children’s literature and its illustration — on the history of American children’s book illustration that sparked Clark’s own dedicated interest in picture book art.

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.