The day Septima left, she said, “I believe I am a promise you are tired of keeping.” Minutes before, Turk had pitched a bottle of beer at her. He had missed, but only barely. Green glass and yellow ale splattered against the kitchen wall. For once, she did not bother cleaning the mess. Septima packed her red valise: toothbrush, comb, talcum powder, three faded cotton housedresses and seventy-two dollars.

As she left their home and ventured into the driving rain, she muttered, “The lies we tell ourselves.”

She’d met Turk, a sailor, at a bar in San Diego the night before he shipped out to the Pacific. Their courtship: six months of enchanting letters. The poetry of his words beguiled her, the sentiments glittering and dancing on the page. She loved the intentionality and tenderness of black ink on white paper, sometimes as many as three missives a week, a prince courting a princess. His adoration buoyed her, transported her to another reality where she felt beautiful and cherished.

Feeling cherished was a first for Septima. She never knew her father. A bar room fight had snatched away his life well before Septima took her first step. Her mother, Ava, loved her with a ferocity utterly devoid of warmth or gentle touch.

A month after Japan surrendered to the Allies, the Navy discharged Turk. A minute off of the ship, he headed straight to Septima’s apartment. The next day, she took him by bus to Oakland, so he could meet her mother. In Ava’s tiny apartment, the three sat down to a Trinidadian feast: curried chicken, corn pie, cucumber chutney and banana fritters. Turk ate heartily, shoveling one forkful after another into his mouth, all the while lavishing Ava with honeyed praise. By the end of the evening, Ava pulled her daughter aside and whispered, “That man, devil blood runs in his veins.”

Septima ignored the warning. Before sleep, she prayed, “Dear God, is this the one?” In retrospect, she had to admit, she did not wait for an answer.

Three days later, the couple found a Justice of the Peace who married them in the blink of an eye, Turk wearing black pants, white shirt, no tie, Septima, a hopeful, sky-blue dress. Ava stayed away, refusing to witness her daughter’s union with Lucifer.

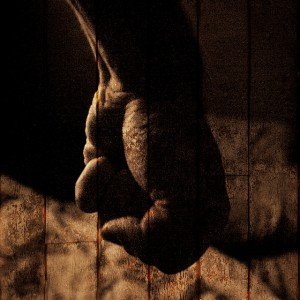

After six months of trying to make the marriage work, Septima could no longer recognize the author of the love letters in the brute whose fists she dodged. She’d lost her savings, which he’d spent on a Harley and booze. Moreover, she’d lost confidence in her ability to discern the character of a person. In the brief time she’d known Turk, she believed she’d lost all she had.

But as Septima dragged and bumped her suitcase along the uneven sidewalk, she realized that she hadn’t lost all she had. Somehow she’d lost more than all she’d had. The arithmetic of love.

Septima poured coins into a pay phone then dialed her mother’s number. Ava didn’t sound surprised. “You can come here. There’s space.”

“There’s space” was debatable. Ava lived in a two-room apartment, one being the kitchen. The second served as a living room by day. At night, it transformed into a bedroom when Ava pulled down a Murphy bed from the wall. Septima knew she’d be sleeping in a brown upholstered recliner scrunched between the front door and window, but she went anyway. She had nowhere else to go.

Those first weeks, Septima spent every hour of her day trying to forget Turk—his words of adoration, his pledge of a love that would outlast time; but also the stench of whiskey that oozed from his pores, the thud of his fist bruising her flesh.

With droves of men marching, walking and limping home from the war, jobs were scarce, especially for Septima who had few skills, other than having operated a cash register for the past ten years. After weeks of looking, she found work at a neighborhood grocery store. On her second night, a lady came in with huge hair up front, and a large ponytail in the back. At first glance, Septima believed she was looking at someone with two heads.

A two-headed woman? No, one woman who had one head and a lot of hair. Perhaps, nothing was exactly as it seemed.

Night after night, as she doled out Kellogg’s Cornflakes and Lucky Strikes, Campbell’s Soup and Borax detergent, the scent and sorrow of Turk slowly faded. She began to slip into the rhythm of the store, looking forward to certain customers, especially Tanya, the two-headed woman.

Tanya told Septima that she worked the graveyard shift, cleaning bathrooms at a nearby office building. Her husband, Eddie, drove a city bus during the day. Each weeknight, Tanya would tuck in her three young kids and kiss Eddie goodbye. Most nights, Septima sold Tanya a Coke and a Heath Bar, and less often, M&M’s. Sometimes, Tanya would purchase lotion to cover the oozing sores on her hands and arms caused by corrosive cleaning fluids. Once Septima asked Tanya why she dragged her aching bones to work, night after night. “My kids. I’m going to see them kids go to college if it kills me.”

In the mostly empty store, they’d talk about daily life. Septima would relate Ava’s latest health woes (hemorrhoids and bunions) or mention a special meal she’d cooked for dinner. Tanya would tell about her son’s “A” on a math test or her daughter’s choir concert.

One night, a young guy came in, gun in hand, pointing to Septima, yelling, “Give me the cash. Now!” In awe, Septima watched Tanya whip around and knock the gun out of his hand. She tackled him to the floor, pinned his arms behind his back then sat on his chest. He could not move and just barely kept himself breathing.

Septima picked up the gun, and considered shooting the man, thought about how nice it would feel to smack violence in the face instead of always being the victim. She believed shooting that guy would sure enough be five seconds of heaven for her. But then she realized the five seconds of heaven would be followed by a lifetime of hell: she pictured his weeping momma, his sobbing girlfriend, a potential orphan-baby. And, she also thought of the problematic God who likely loved both this particular criminal and that damn Turk. Moreover, a God who maybe even loved her, too. So, instead, with her thumb and index finger, she lifted the gun from the floor, and put it behind the counter. She dialed the police who arrived in a heartbeat, just seconds before the thief was about to suffocate.

The grateful storeowner gave each woman a cash reward. A small amount, but big enough that on a Saturday night a week later, Septima, Tanya and Eddie went out to dinner at a place with white linen napkins and tapered candles on the table. They ate shrimp cocktail and lobster bisque and hot parker house rolls and roasted asparagus and Caesar salad and filet mignon and tiramisu for dessert.

Bathed in candlelight and surrounded by servers who aimed to please, the three relaxed, allowing themselves to imagine, thereby unshackling a flurry of dreams. Timidly, at first, then emboldened by a second bottle of wine, they each hoped aloud—Eddie pictured a yellow house with a white wrap-around porch, far outside of the grimy city. Tanya envisioned a day job, maybe at the library, with hour-long lunches so she could read one book after another. Septima dared to believe she could put aside money to go to night school, maybe train to be a chef.

At the end of dinner, Eddie raised his glass to the women, “ A toast, a toast to us all!”

Septima allowed herself to feel a warm affection for Tanya and Eddie. And miraculously, she managed to direct some of that affection toward herself, toward her whole self, both the part that’d made the missteps and the part that seemed to be back on some path, wandering as it might be. She nodded and clinked her glass against each of theirs. “Cheers.”

Share this post with your friends.

One thought on “The Arithmetic of Love by Deborah Prum”