About a dozen years ago, I was in Wexford, Ireland, to meet the artist Bridget Flannery for lunch. We exchanged gifts. Hers was a handsome print of a recent painting, which now hangs in the foyer of my house. Mine was a signed copy of my book.

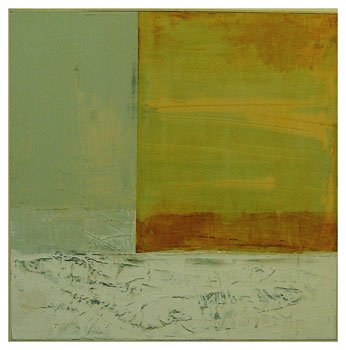

Oh, Katherine, she laughed, I’ve bought a dozen copies of this book and given them to friends. Then we went around the corner to see her new exhibition. The centerpiece was a large abstract, from her series Pause.

I was drawn to it immediately. She said, The image comes from your book. What? I said. Your book, she replied: that passage about the ice on the lake. I could not recall it.

I asked if I could buy the painting, but it had already been acquired by the county council, and she had commissioned a well-known calligrapher to inscribe the passage for presentation.

The wind, an east wind, tore at the trailer. Out on the lake, the ice melted, froze, melted: flashing sheet-ice reforming; beneath it, the ice was solid, and went deep.

Pleased, I bought a smaller painting from the series. It is on my study wall.

A few years ago, I received an email from a woman in Alaska who had read my book and asked if I’d phone her to discuss it.

Curious, a little wary, I phoned the woman I remembered from thirty-odd years before. She pointed me to the passage in Narrow Road in which she had found herself. The narrator, a version of myself as I was then, was a visiting poet in her Dena’ina Athabaskan village, on the far side of the Alaska Range from Cook Inlet. She couldn’t have been more than thirteen. She approached me with an essay and asked me to read it. I was impressed, and was saddened. She could handle words, she was learning how to organize her thoughts, but the school (I wrote) would do nothing for her, and she was going to have trouble because she was bright and knew her own mind.

That part had meant a great deal to her, she said. “It was like a warm bath.” She did have troubles, really hard times, but had made her way through them and gone to college. She had joined the National Park Service as a cultural anthropologist, working to amplify her people’s voices. For nearly twenty years she had carried their voices, she said, but—she couldn’t hear her own voice. Anthropology dissatisfied her. She had turned to literature. She was beginning to write poetry. She had enrolled in a graduate program in literature and cultural studies.

She is a writer. We’ve become allies and friends; we talk on the phone when we can. She carries that passage on a paper she keeps folded in her wallet.

I sat down and read a finely-thought, lyrical essay on freedom. She had described the sunny day in loving detail; then described how it felt to be cooped up in darkness, in school all day, like a caged bird.

Like a caged bird. I looked at her face. It was pretty, intelligent, still unformed, a teenaged-face; but in her eyes was knowledge that made her resistant, but also petulant. She knew, was beginning to know, how to write, to compose and to think: but this school, I guessed, was not going to do enough for her, when she needed an education. In her theme flashed a spirit that ought to be protected from rote obedience and the limits of the narrow curriculum, from its dulling effect on the mind. She was fighting it in her own way, the only way she had; she was going to face trouble because of that.

The imagination is so strong, and is so terribly fragile, easily wounded, quickly put to sleep. Yeats cautioned that we must take care with the young: Only encourage, he said, encourage the young poets. The young, who need all that poetry can give them: a truth, spoken and unbreakable; the sound of a clear voice; astonishments of language formed and informed by its content; the rigor of that form. They need its beauty. They can, themselves, make poems: poein, from the Greek, means maker. They love to make, and they want to make their poems well. They would see what poets had made; they would listen to what they themselves had made. I would say, and keep saying, yes to them.

The wind, an east wind, tore at the trailer. Out on the lake, the ice melted, froze, melted: flashing sheet-ice, green water riffling in the wind. It was only the surface forming and reforming; beneath it, the ice was solid, and went deep.

Katherine McNamara is the author of Narrow Road to the Deep North, A Journey into the Interior of Alaska, and was the founding publisher of Archipelago (1997-2007). She directs Artist’s Proof Editions, where she designs and publishes books of art, poetry, and Native American writing for the iPad. She makes video poems and works on paper. In 2017, the paper archives of Archipelago and Artist’s Proof Editions will be on exhibition in the Rotunda, University of Virginia.

Katherine McNamara is the author of Narrow Road to the Deep North, A Journey into the Interior of Alaska, and was the founding publisher of Archipelago (1997-2007). She directs Artist’s Proof Editions, where she designs and publishes books of art, poetry, and Native American writing for the iPad. She makes video poems and works on paper. In 2017, the paper archives of Archipelago and Artist’s Proof Editions will be on exhibition in the Rotunda, University of Virginia.

Along Creek Inlet, photo above by Katherine McNamara

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.