Freedom. Freedom to explore. Freedom to express one’s self. Freedom to communicate your conscience. Artist Robert Strini has been answering the call for over 40 years.

“The biggest key in my life was when my father said to me, ‘I don’t care what you do or how much money you make, as long as you love what you do,'” says the son of a country Italian butcher who loved his trade. Strini’s father also took his young son to lectures on the power of positive thinking. His mother was a generous-hearted, hands-on homemaker.

Given his parents’ encouragement, Strini’s creativity flourished as a child in Hayward, California, near San Francisco. “At an early age, I discovered that art was a field of interest that engaged me fully. I was always making things, usually from found objects or from pieces of broken toys.”

Strini, now a Scottsville, Virginia resident for 25 years, loved the “no rules” aspect of art as well as the chance to explore his passions in his own aesthetic language. He became “addicted to clay” at San Jose City College. He later received an MFA in art at the University of California at Berkeley.

At UC, he was inspired by conceptual ceramicists Peter Voulkos and James Melchert. “Voulkos and Melchert were then the gods of ceramics and sculpture. They changed the whole dynamic as clay became a sculptural medium beyond the traditional forms of pots, containers and bowls.”

Strini was influenced by his innovative mentors to test the limits in his own ceramics. “I started to paint clay. I covered clay with leather, zippers and flocking. I really pushed the material in a sculptural way.”

His inventive ceramics portfolio won Strini the Rome Prize Fellowship in Sculpture in 1971.

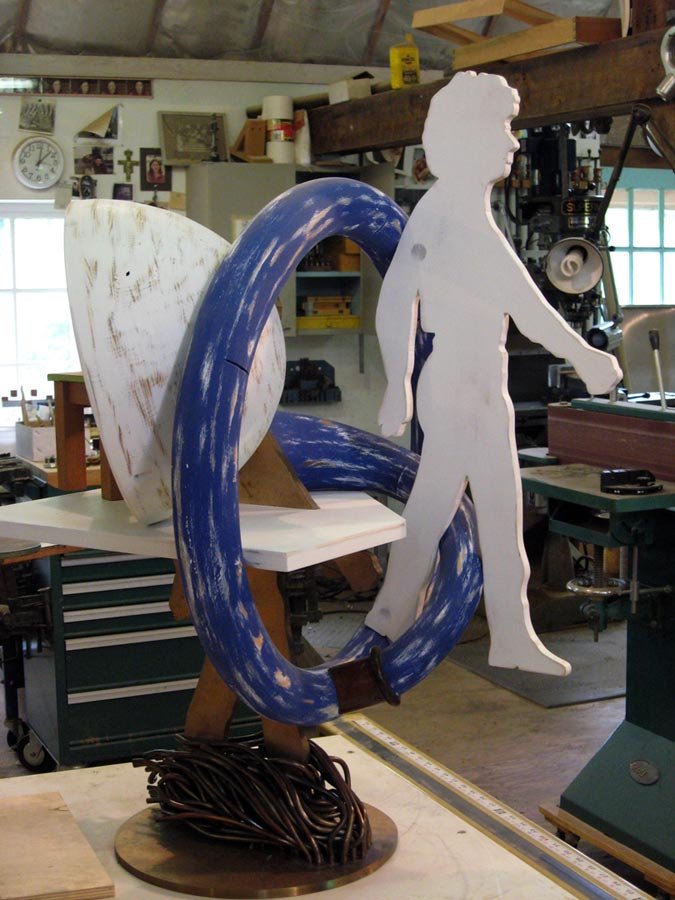

The prestigious prize afforded him two years of freedom to experiment further with new ideas and forms. He started to work seriously in wood, producing both abstract and representational pieces. Bikes and musical instruments particularly intrigued him.

As original and elegant were his wood pieces, Strini eventually felt something was missing. “The early wood pieces were becoming beautiful but were kind of empty for me. I was leading to a point where I wanted to tell some kind of story other than I can make this out of wood.

“So the natural transition was to go from the craft to the more artistic expression. Craft is when material overpowers the idea and art is when the idea overpowers the material.

“All artists start out learning different techniques and you get sucked in by the materials. Social commentary kicked in when mastering techniques and materials was not enough. Every single piece has to question me as an artist. It has to be a challenge. It can’t just be a repeat.”

Glass chair questions the idea of opposites. “Everything in that chair is opposite—from cold to hot to hard to soft; from clear to opaque. The glass pierces that chair and makes it impossible to sit down on,“ says Strini.

“I love texture. I love hot and cold. Light and dark. Smooth and rough. As I’m working on a piece of art, I’m feeling these different textures. They’re all metaphors. They all mean something.”

Strini redirected his work to a more personal narrative and concern. Dialogue (1982-83) was an early tableaux stirred by the death of his dog. “I incorporated polaroid photos that had been tacked on the studio wall. I realized the photos were a language. I use a lot of symbolism and metaphor—the dog is walking off a blue beam—the beam of life. The I-beam represents strength. Compared to my wood pieces, there were now two different things going on.”

Strini’s Hunting Trip stands 6 to 7 feet tall and incorporates a ’47 Hudson car door and steel chair on a red dolly. The piece was triggered by the sight of a deer strapped to a car’s front fender in Montana. “Blood was trailing back over the car. There was this disrespect for death. It’s part nature and part religious, the crucifix form. The table is balanced above the door. The idea is that everything is balanced.”

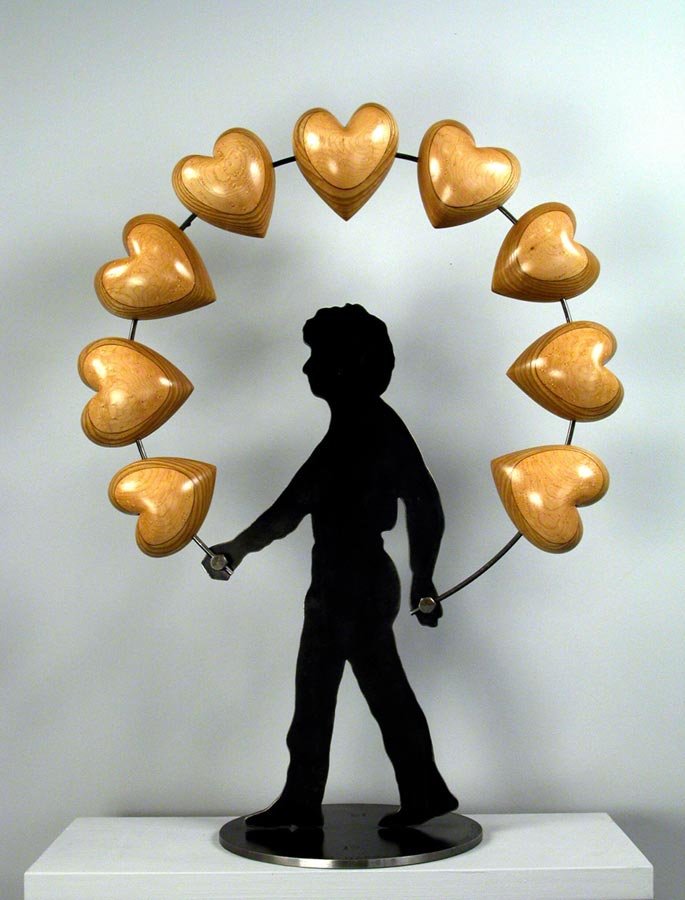

And Strini kept exploring new stories and mediums; many featured the human heart. “I have a heart issue so I embraced the heart during this creative process. I made my first heart in wood and then covered it in bronze. From 2002 to 2008, I made many pieces in bronze. The nice thing about bronze, it’s permanent.

“The heart is the main organ in my body. It’s the key to my existence and is an important symbol. I use that symbol—and I also use the crucifix—a lot.”

Genocide, a 1998 installation for the University of Virginia, portrayed the human heart at its most vulnerable. A darkened room was covered with children’s clothing dyed red. Six speakers broadcast peoples’ stories of how genocide changed their lives.

“It was a painful piece to do,” Strini admits. “One woman talked about being raped 600 times. A little boy talked about losing his hair. There were sounds of my heart beating mixed with Mozart’s Requiem.

“As one passed, the hearts lifted—the heavy stones weighed 2-300 pounds—and then dropped on the floor. It was a loud bang, the sound of death. There were 12 hearts on tripods with tiny light bulbs. Your eyes adjusted but it was very dark and very scary.”

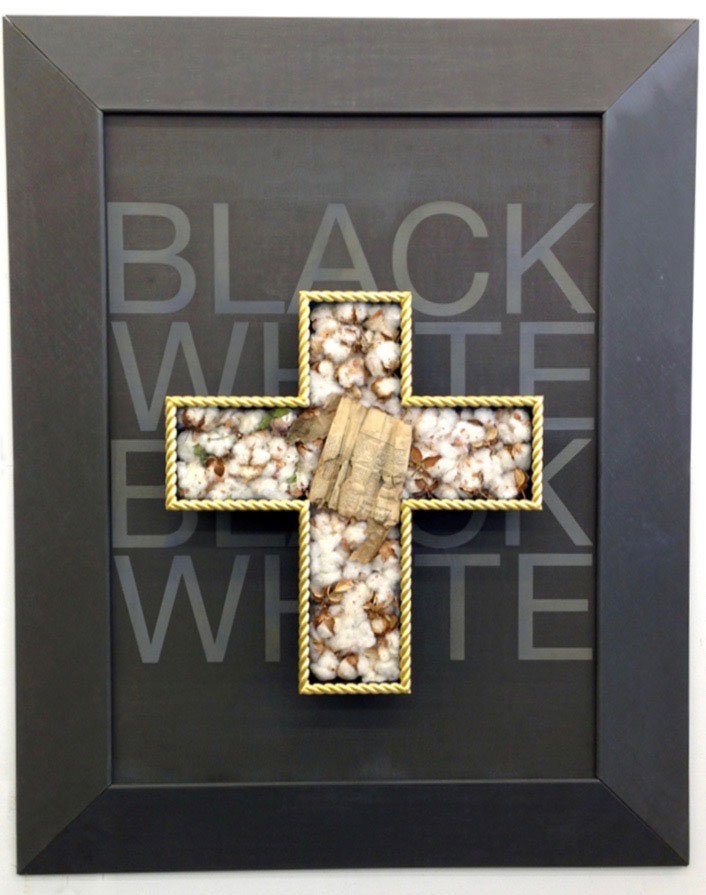

Strini further considered matters of freedom and conscience represented by the heart as well as the cross. “The crucifix is used more as a metaphor of awareness. A crucifix draws attention,” says Strini, memories still fresh of being raised with “with total 100% catholic guilt.” “A lot of people, however, misinterpret the crucifix thinking I’m super hyper religious.”

Fifteen years ago, Strini found a newspaper stuffed in the wall while remodeling his daughter’s bedroom in the family’s Scottsville farmhouse. It read “30 Negros for Sale in Scottsville, VA, 1848.” “Holding this paper took me back to that terrible time.”

Strini saved the newspaper and recently created Reliquary, a 2.5” lead crucifix housing the historic paper cushioned with raw cotton. The cross is framed in a gold rope wooden frame.

“In Italy, reliquaries are everywhere…a piece of bone, a piece of hair of St. Clair are put in little glass boxes. I wanted to put the newspaper in this crucifix shape in cotton as a reliquary. I wanted to add some importance to it. It’s Virginia. It’s Scottsville, Virginia. It’s really what happened. I dedicate the piece with love and respect to all those who suffered.”

Strini, a teacher for many years at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., looks to the future, feeling all the more concerned and grateful for the freedom to express it.

“When I taught, I pushed the idea that it’s OK to not be safe. It’s OK to be on the edge and to challenge to status quo.”

“I used to tell my students, ‘the greatest freedom of an artist in our country is that if you object to something that the government’s doing, you have a choice. You can take a gun and you can go shoot at the White House and be put in jail, OR you can do a piece of art.’ If you do the piece of art, you’re totally free to express yourself any way you want about anything that’s bothering you. What excites me are things that question.”

Strini laughs. “Look at the White House now. They’ve drained the swamp and put billionaires in there. It’s perfect for ‘a ship of fools’ piece.

“I’m grateful for the freedom I’ve had. I’ve have really had a great time making my work.”

In July, three of Strini’s wood pieces, Goolagong among them, will be shown in New York at the Mathew Marks Gallery in Chelsea.

Strini’s work is exhibited across the U.S. and is represented in collections including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; the Oakland Museum of Art, CA; the Tacoma Museum of Art, WA; and the University of Virginia Art Museum, Charlottesville, VA. Visit robertstrini.com to see more of Strini’s work.

—Elizabeth Meade Howard, art editor

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.