by Mary Carroll-Hackett

I move too fast. Always have. I talk fast, walk fast, read quickly, even had to be taught as a child to slow down while eating, Mama saying things like It’s not a race, Mary, or You know no one’s coming to take that away from you. I was the child she had to keep by the hand if she were to keep me from running too far ahead in stores, racing my way up stairs and escalators, or headlong down them.

Sometimes that speed has worked to my advantage, later, as an adult, in the corporate jobs I had before finding my way back to the study of writing, and at times, in that study as well, especially when it came to the balancing act of completing my low-residency MFA study at Bennington while teaching a full-load of composition classes, all the while also being a single parent to three kids, one in elementary and two in middle school. That innate tendency to accomplish things in a hurry let me grade that stack of freshmen papers in the required two hours of sitting on the bleachers for my son’s pee wee baseball practice, to finish my required graduate reading assignments while waiting in school parking lots for the last bell to ring, and to plow my way through both the requirements for my job and for my MFA program in my two days off a week. Yeah, that lifetime habit of hurry-up served me well—at times.

Where it didn’t benefit me, I learned again and again, was in my writing. I wrote quickly too, but produced massive messy overwritten drafts, filled with repetitive circling, blurry reams of words lacking structure and control. Revision was a long and arduous process of cutting and cutting, ferreting what needed to be there and what didn’t in the overwhelming paring back of the mess I’d produced.

I tried to slow down. Really I did. Over the years several teachers tried to help me learn to slow down. The beautiful Betsy Cox had me reread Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, but I was only allowed to read three pages a day. Liam Rector suggested I do more memorization. Still I read, and wrote, too fast, making that mess, missing nuance and opportunities in so much of what I wrote. I had to do something, make some kind of change. My writing needed it.

The answer came one sunny afternoon, during our June residency. I was sitting out on the grass in the shade of the trees cornering the Commons building on Bennington’s campus, looking out over that green that only Vermont’s Green Mountains offers, when, out of nowhere, that amazing Southern novelist Barry Hannah dropped into the grass beside me. I had met Mr. Hannah twice already that residency, the first time when his four year old grandson had turned the compact folded-up umbrella he carried into an imaginary gun, making those hysterical Pew! Pew! Brattatatat! shooting noises only little boys can make. I walked behind them on one of Bennington’s wooded paths, and having a son around the same age, I recognized the disappointment on his face that no one seemed to realize what a powerful cowboy he was being. So when he pointed the umbrella at me—Pew! Pew!—I did the only thing, as the Southern mother of boys, I knew to do: I fell to the ground, clutching my heart. From behind my closed eyes, I heard his squeal of delight as he yelled, “She played, Papaw! She died!”

When I opened my eyes, I looked up into two faces, the little boy still gleeful that I’d played along, and then I gasped as I realized that “Papaw” was no other than acclaimed Mississippi writer, author of Airships, and the stunning novel Yonder Stands Your Orphan, among others. He laughingly helped me back to my feet, and thanked me for playing along with his grandson, and then he hurried to catch up with the little boy, already off to his next adventure. This was my introduction to Mr. Hannah.

The second time occurred two days later, as friends and I stood outside the Commons area, having drinks before dinner, when Mr. Hannah approached me, weaving through the crowd, an unlit cigarette hanging loose between his fingers. “Hey,” he said, “You got a light?”

I did. I handed over my lighter. He lit his smoke, then promptly pocketed my lighter, and walked away. I stared after him, then looked up at my friend Whit, and said, “Um, Barry Hannah just stole my lighter.”

Whit laughed, and said, “Go get it.”

But I was still too starstruck, too shy, so I shook my head, saying, “Naw, it’s all right.”

Whit had no such shyness. He took off through the crowd, and in a minute, returned, not with my lighter, but with Mr. Hannah. Both were laughing. Mr. Hannah winked, and said, “Did I forget to give you something back?”

I nodded, and watched as he dug in his jeans pocket, and came up with a whole fistful of lighters, in all different styles and colors. He asked, laughter in his eyes, “Which’n yours?”

I picked my lighter from among the handful, thanked him, and he nodded, laughing, and walked away.

Now, several days later, here he was again, sitting in the grass beside me, and grinning. By this time, some of my shyness had dissipated, so I said, “Well hey,” grinning back. “Should I hide my lighter?”

He laughed, and said, “I think you’re safe. But—” He shaded his eyes against the sun, and said, “I been talkin’ to some folks about you, and—” He winked, a gesture I was now familiar with, and said, “I hear you’re fast…” He deliberately played out the last word.

I laughed, and exaggerating my own already pronounced Southern accent, I fanned my face with my hands, and batted my eyes, replying, “Now, Mr. Hannah, I do declare, you know where we come from, saying that is not a compliment!”

We both laughed, and then he patted my hand. “I have been talking with your teachers about you, and I hear you’re struggling with slowing your writing down.” He brought one finger up and gently tapped at my temple. “That brain running away from ya, so if you don’t mind, I’d like to make a suggestion.”

Sure, I said, humbled that he’d take the time, and happy to hear anything that could help my writing improve. He leaned back into the grass, and said, “I want you to go to one of them pawn shops they got down there in Carolina, and I want you to find yourself an old, solid, dependable typewriter.”

“Typewriter?” I asked, “Please tell me it doesn’t have to be a manual.”

He cackled, and said, “No, it can be electric, but it will, I promise, help with some of what you’re struggling with.” He took my hands into his, and said, “We forget. We tend to think of this writing we do as an intellectual pursuit, but in truth, it belongs to the body as much as it does to the mind. Your teachers tell me that you’re an intuitive writer, that it all just pours out of you in a mad rush, so what we need to do is to slow the body down a little bit.” He lifted my own hands up like something I needed to see. “If we slow these down—” He released one of my hands, and tapped my temple again. “That will give this a little more time to work, at a slower pace.”

I nodded, thanked him, and he got up, leaving me there in the grass.

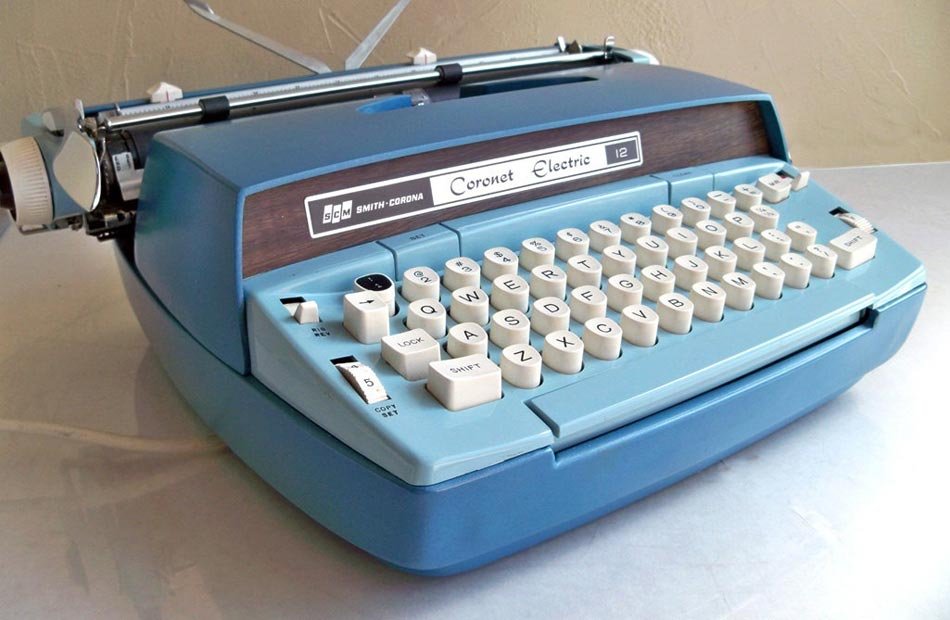

I did what he said. When I got home, I made my way through a couple of the pawn shops in the area where I lived, and in the second one, I found a 70’s era blue Smith Corona Coronet Electric Typewriter and I bought it. I carried it home in its hard clunky case, and set it up on my dining room table. I rolled blank paper into it, and set my fingers to the home keys, and started typing. The feel, at first, was awkward, like trying to remember something. Even though I typed all the time on my computer, this was more physical; my fingers had to press a little harder on the raised white keys, and then there was the return, the little ding! at the end of each line, the clack-clack of the keys, the actual physical movement of the paper as I typed line after line. It took me back to late nights, at thirteen and fourteen sitting up in my parents’ kitchen, painstakingly typing out poems on my dad’s favorite onion skin on his old manual upright. It took me back to the letters pressed into the ribbon, and having to reload the machine with paper for each new page. I couldn’t just backspace and things disappeared. Even if I wanted to backspace, it became a deliberate conscious action, as I overtyped a line of capital XXXs over something before I moved on. It was glorious.

I did what he said. When I got home, I made my way through a couple of the pawn shops in the area where I lived, and in the second one, I found a 70’s era blue Smith Corona Coronet Electric Typewriter and I bought it. I carried it home in its hard clunky case, and set it up on my dining room table. I rolled blank paper into it, and set my fingers to the home keys, and started typing. The feel, at first, was awkward, like trying to remember something. Even though I typed all the time on my computer, this was more physical; my fingers had to press a little harder on the raised white keys, and then there was the return, the little ding! at the end of each line, the clack-clack of the keys, the actual physical movement of the paper as I typed line after line. It took me back to late nights, at thirteen and fourteen sitting up in my parents’ kitchen, painstakingly typing out poems on my dad’s favorite onion skin on his old manual upright. It took me back to the letters pressed into the ribbon, and having to reload the machine with paper for each new page. I couldn’t just backspace and things disappeared. Even if I wanted to backspace, it became a deliberate conscious action, as I overtyped a line of capital XXXs over something before I moved on. It was glorious.

And I came to learn, it wasn’t just the physicality of typing on a typewriter that slowed me down. The even more valuable slowing came after I’d typed up a story, or a poem, on the typewriter, when I had to retype those pages, from start to finish, into the computer. This became the heart of my revision process, the retyping, the slight distance it gave me, the much slower rewriting process where I could much more easily see where I had been too repetitive, or where I had overwritten, and make much more considered decisions of what to leave in or take out—all as I retyped those pages created on the typewriter. This two-step start to anything I wrote became the best thing to happen to my writing process, and more, to my revision process. Even if my mind raced forward, the sheer physicality of the typewriter and the retyping slowed me down, the different interaction required between my hands, my body, and my brain, slowed me enough to see my own work as I never had before.

I still use that old blue typewriter, the clack-clack sound now filling my own house in the late night hours as it did my parents’ when I was a kid. I love the push of the keys under my fingers, the broad 70’s blue presence of it on a desk in the corner of my bedroom, the tug of the paper and roller when I pull a completed page out and add it to the pile growing on my desk. What a gift it is, and what a gift it was the day Barry Hannah, in an act of life-changing kindness, took five minutes with a young writer, grinning and winking as he said, “Girl, I hear…you’re fast!”

Not anymore, Barry, thanks to you, and Old Blue.

–Mary Carroll-Hackett

Share this post with your friends.