Once a decade, the European cities of Venice, Kassel, and Munster form a trifecta for the contemporary art world. There’s the every-two-year Biennale in that glorious jewel on the Adriatic.

And a mammoth show every five years organized by an internationally-known curator that spreads throughout the mid-sized German city of Kassel.

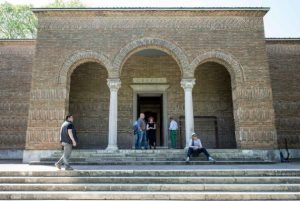

And every ten years, Munster—with its town center entirely rebuilt to its historic appearance after World War II—hosts an exhibition of new outdoor sculptures and installations.

This was one of those years when all three coincided. Over the course of two weeks, I saw thousands of works of art, mostly new but some classic modern and historical art, too. As ever with these extravaganzas, the experience was by turns enlightening, maddening, and tedious. And the process of sorting out my thoughts will continue for months.

The Biennale is the oldest of its kinds, started in 1895. There are now over 200 of them around the world. The experience in Venice comprises multiple parts. At its core is an international group exhibition, staged in the Central Pavilion of the Giardini (gardens) and in part of the Arsenale (an enormous historic naval and military enclave), organized by a star curator, this year Christine Macel from the Pompidou Center in Paris.

Then there are eighty-four National Participants: solo or group exhibitions organized independently by the home countries in separate national pavilions located in the Giardini, throughout the Arsenale, and at other sites around Venice.

Some criticize the continuing presence of these pavilions as an antiquated nationalist structure, but I love walking from one to the next, many designed by well-known architects like Josef Hoffmann, Gerrit Rietveld, and Alvar Aalto, as if taking a quick trip around the world. It reminds me of a place called Storyland that my grandparents took me as a child on Cape Cod—a clear fiction that nonetheless delighted and transported.

There are also a dozen collateral events—performances, installations, and exhibitions—organized by private foundations or commercial galleries that tag onto the main events. There’s an educational program, including ongoing lunch conversations with the artists. And there are various independent museums, foundations, and other arts organizations putting their best foot forward with important exhibitions. To see it all would take about a week.

Macel’s group exhibition was generally panned in the US press for a soft politics that made it seem dated or even irrelevant and for a fuzzy organizing structure. I disagreed. It wasn’t just that I encountered lots of great works. I also admired the curator’s stance: Yes, times are tough and the world’s going to hell in a hand-basket, but there are plenty of examples of creative resistance that involve imagination and community and whose utopian slant offers an intentionally hopeful attitude. Here are a few of the many works that stood out for me.

Lee Mingwei

What I saw was one man sitting quietly in a wooden chair in the little Carlo Scarpa-designed garden. What I read was that at any moment a woman dressed in traditional East Asian robes might appear bearing a letter from the artist, which the visitor is instructed to take and open “whenever beauty visits.” An enigmatic, poetic piece, whose gift of a personal and private experience offered a marked contrast to many of the more public works around it.

Olafur Eliaason, Green Light: An Artistic Workshop

The room is filled with workers from Nigeria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Syria, and China, constructing wooden polyhedron lamps. They’re immigrants and asylum seekers, and the project is meant to give them work in exchange for food and helping them acclimatize to life in Italy. There was lots of criticism about it being one more example of putting the Other on display, like a human zoo, but I found it important— an example of an artist creatively problem-solving and having a real social impact, and resisting making high-priced baubles for high-net-worth individuals.

Marwan

I’ve seen paintings before by the Syrian born artist Marwan Kassab Machi who was based in Berlin until his death last year, but never an entire room of all self-portraits spanning some thirty years. I loved their vulnerability, awkwardness, and interiority. These are two earlier ones.

The later ones become positively unhinged, in the best way.

Francis Upritchard

Who gets to use what group or culture’s imagery, language, signs, and symbols has lately become such a contentious issue. So I was surprised to see these overtly “ethnic” figures by the London-based New Zealander Francis Upritchard. They’re in a section called The Pavilion of Traditions that reflects on the intersection of

colonialism, appropriation, fundamentalism, and nostalgia. I found them intriguing and disquieting.

Sheila Hicks

The far end of the Arsenale has often been a place for showstoppers and Sheila Hicks’s monumental wall of colorful knit works doesn’t disappoint. She’s the doyenne of textile art and is deeply attuned to the social and cultural implications of her woven sculptures, as well as their visual appeal.

John Latham

I’ve only ever seen British Conceptual artist John Latham’s work in bits and pieces while traveling in Europe, and here was a chance to see a room full. There’s an insistent, aggressively quality to the work that I respect. It’s as if he trusted his ideas to determine the form without over-fussing with the aesthetics. And yet I find it beautiful, as well as thought provoking.

Kiki Smith

I loved mid-career American artist Kiki Smith’s room, especially the drawings. They were part of the section called Pavilion of Joys and Fears. Smith says they’re about people and their energy. Most show one or two people, but this group portrait of four women stood out for me. I don’t know who they are, but I’m intrigued by their specificity—like a group of her close friends—combined with their aura of being timeless heroines.

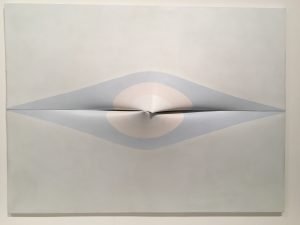

Zilia Sánchez

These paintings were part of the section called Pavilion. They fit right in with the North American shaped painting movement of the 1960s, except she’s Cuban and started making them in the 1950s. They have a simple geometry that connects to Minimalism, but she slyly inserts allusions to the female body, giving them a strange, playful sensuality.

Philippe Parreno

I didn’t entirely get this piece, but I did spend some time trying. I understand that Parreno is working with light and sound to create something he calls “quasi-objects,” meant to be inseparable from the context in which they’re exhibited. In this case, sensors in the plexi caused the overhead lights to flicker in response to viewers’ movements, and a sonic cloud somehow factored in. No one even stopped to look.

Liliana Porter

From multiple everyday objects, Argentine artist Liliana Porter constructs a narrative that swells to take on the course of empire. It’s a brilliant and endlessly engaging meditation on the order of things, as Porter describes it, using Foucault’s famous title. Called Man with an Axe, it includes broken furniture, shards of ceramic, and flea market figurines—the protagonist at lower right, who seems to start a chain of events, including gunfights, broken vases, falling pianos, and stranded ships.

John Ravenal has been the Executive Director of deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum In Lincoln, Massachusetts since January 2015. He was the Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts from 1998-2015. Before that, he was the Associate Curator of 20th Century Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where he worked from 1991-1998.

Ravenal’s focus as a curator has been on working with living artists, including Chuck Close, Sally Mann, Xu Bing, Jaume Plensa, Ryan McGinness, Diana al Hadid, and Robert Lazzarini. He recently organized a major international exhibition of work by Jasper Johns and Edvard Munch, in partnership with the Munch Museum in Oslo, where it opened in 2016 before going to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Ravenal earned his MA and MPhil in Art History from Columbia University. In 2009-2011, he served as the fourth president of the Association of Art Museum Curators. He was a 2012 Fellow at the Center for Curatorial Leadership.

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.