I am floating in near total silence in the women’s bathhouse at the Jefferson Pools, a natural mineral springs in Bath County, Virginia. Surrounded by six other women, some nude, others in bathing suits, there’s only the swish of a raised arm or a sigh when we reposition ourselves on the bright and squeaky Styrofoam noodles provided to keep us afloat in the warm, clear water. Enclosed by an aging wooden roundhouse, its whitewashed walls speckled with green mold, the pool is deep with a stony bottom and bounded by sparse curtained dressing rooms. It’s capped with an open-air skylight, rising some twenty feet above us. On this autumn afternoon, temperatures falling, I watch high cumulus billow as we seven float past one another like septuplets, still and wordless in the warm wash before birth.

I am a physical coward except in this one regard: I’ve given birth. Four pregnancies. Two un-medicated labors and deliveries. Two miscarriages—the second, at twenty-one weeks, especially painful. Childbirth stripped me of bodily modesty and fear, not pregnancy—in which a woman’s body shape-shifts into a soft mountain range of abdomen and breasts, topped by luxurious hair and a head governed by anxious dreams, body grounded by swollen feet—but childbirth and its bloody labor, its sheer athleticism, and the self-forgetting required for one body to push another body into the world.

What is the most uncomfortable thing you’ve ever worn? Was it ugly? Like pantyhose—oddly intimate, a manufactured second skin, either too small—slipping down over hips and belly—or too big—wrinkling into saggy elephant ankles? Or was it a garter belt with metal clips and straps that pressed into your skin, biting into the slick, thick thigh of nylon hosiery? Was it beautiful and painful and meant to be seen—tight jeans, an itchy wool sweater, too-high heels? Or was it something hidden?

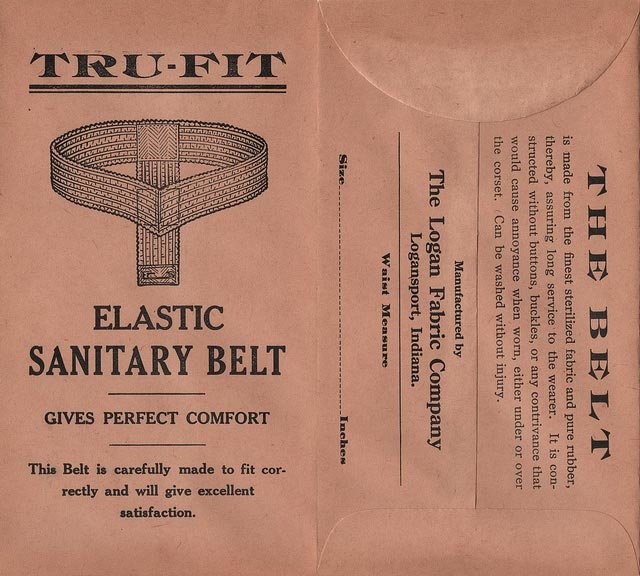

Are you old enough to have worn a sanitary belt? I am. Before the invention of self-adhesive sanitary pads, women wore sanitary belts, bands of hospital-white, thin fabric with elastic woven through that hugged the waist, rigmaroles of straps, grommets, and hooks that held the napkin in place. Inevitably, though, the whole contraption shifted if you ran or reached above your head, risking a leak of the unspeakable onto your underpants and clothes.

The leak. So embarrassing. My friends and I constantly watched for one: “Tell me if I’ve leaked.” Leak: to tell a secret, to tell the watching world, “This one is ripe.”

When I am in the eighth grade, Stephen T. follows me home after school every day. Stephen is not one of the neighborhood kids I’ve come to know over the years as I and my brothers and sisters roam the neighborhood woods and creek. His family is quiet, small in number. They generally stay indoors and don’t run riot over the lawns and streets like my siblings and I do.

As I walk home from the bus stop near his house, he waits, watching. Just as I pass his driveway, he slams through the aluminum storm door and falls in, never speaking, remaining two or three steps behind me. When I quicken my pace, he speeds up, too. When I cross the street at an angle, bent towards home, he turns, too. Should I turn and yell at him or just keep moving? Each time, I’m afraid.

In my memory the street is always empty, and I’m unable to imagine any other way home. I reach the creek; one more house to go. Stephen is a ROTC boy, thin and serious, black frame glasses, and a shock of dark hair. I’ve looked him up in a friend’s yearbook: chess club, JV track. I am no runner, but I begin an awkward lope, juggling books, coat. At the edge of my front yard, he falls away, disappears, the routine ended for today. I hurry through the front door and close it. By the time I’ve told my mother and we’ve rushed to the window, he is gone.

You must suffer to be beautiful. The first time I hear this is from my mother’s lips as I wince under the unskilled hands of Janet, her best friend, who is giving me a stinky home perm. I am five. Next to me and equally miserable, Janet’s daughter, Susan, also getting a perm. We will be flower girls in a wedding a few days hence. My stick-straight brown helmet and Susan’s thin, strawberry blonde tresses are unacceptable to the bride, and so we suffer the rotten egg smell of the perm solution and the misery of rigid plastic rods wrapping our hair too tightly against our tender scalps.

Afterwards, though, I know that we are beautiful. Everyone says so.

Share this post with your friends.