When I was a child, Moab terrain served as backdrop for macho trucks suddenly dwarfed like hood ornaments atop massive mesas, the sun blazing rays from which, within seconds, a Chevrolet logo would emerge.

In a photo of Moab terrain, Doug half crouched with his bike on a flat rock precipice, the Colorado River murky in the canyon’s distance below its edge. In the frozen moment, a smile spilled across his face completing the image of energy about to explode into motion. I chose this photo for the cover of his funeral program.

A year later I drove past the entrance to Arches National Park feeling its call, a mystical promise that some resolution could be found in this place. As winter stretched before us, the entrance soon behind us, I promised out loud, “I’ll be back.”

I landed in Las Vegas finding my car.

Urban density and electric bling disappeared I started into new terrain of sage dotting dusty flats from which rock rose, horizontally lined in layers etched by water and time.

I have always loved the smallness of cattle against mountains. My camera in hand, I alternately zoomed and widened its lens taking shots as we passed through subtly changing landscapes. For one stretch, a succession of semis in primary colors lumbered uphill. My hand worked the lens to store those images. Continuing, I snapped a vein of blue mountainside, a snowy crater, dreamy shapes through a veil of field dust and striations of cloud patching over the sun.

It was only later, looking at many of these images that I said to myself, “The landscape would not have its power without roiling clouds, clouds clinging to mountain tops, clouds breaking electric glare into bands of sweeping color, or a single wisp like a jet trail cocked at an odd angle as if marking a particular point in the landscape.”

Don Graham. CC license.

Sorting through my own thoughts, I felt the landscape tease me ever closer to my destination with new offerings of color and rock formations. Green fields gave way to articulated layers of orange between which, houses and utility poles angled like gluedowns or afterthoughts. A sudden junkyard created a crop of metallic color behind barbed wire fencing. Upward sweeps of charcoal—magnesium and other ore—broke sandstone formations. A sudden stovepipe reached skyward above smaller angled hills. Green showed above the charcoal, yet another mineral appearing in a red mountainous stand. The sheer beauty of the place at once called me into the landscape and made a knot in my throat as I thought how much Doug loved this place, had returned to it, and would have liked to return with me.

A flurry of calls over my Bluetooth speaker interrupted my reverie. The sky blackened above. In the distance, rain clouds opened in all directions. I arrived and pulled in to sit out the storm at the condo where friends stayed before setting up our own campground.

***

The wind and rain built in ferocity until the storm had emptied and exhausted itself. When the skies lightened again, we set out for the campground laying tarps, erecting tents, and clustering supplies on the central picnic table.

The tent I had brought was a relatively new one Doug bought for its lightness, a requisite for backpacking trips. Having never used it, I had set it up at home to be sure I would know how it fit together should I have to set up in the dark. The stakes and collapsed poles I pulled from stuff sacks felt familiar. As I worked, I traveled the distance from growing up a city child to camping with Doug for the first time in college. How much had changed from those days of relying on his direction to choose the spot, clear debris that could pierce a tarp, and place the tent with poles and stakes that made a sturdy shelter! What I had learned from his love of nature was my own love of being there with him, my own love of being there.

I tossed the fly over the ridge, snapping it to the tent frame, stretching and securing its corners with stakes. I could almost hear him narrating proper setup.

Our activity took on a businesslike efficiency in the falling light. Nevertheless, I heard my friend, Simon, say, “This is the campsite we were in the last time we were here with Doug.”

Simon pitched a central canopy, and hung his solar shower from one pole, a ritual I imagined he and Doug also did years earlier. I carried on my preparations with a heightened sense of destiny, remembering the promise to come here, the knowledge that I would, efforts that at first failed, then the invitation to this trip and our arrival to the exact place where Doug had been. For the rest of the week this would be home: it was a beautiful site.

The 20 x 30 patch of red sand was cornered on two sides by gently sloping slick rock making an easy climb to the higher rounded ledges and the valley view. The sides not bordered by rock opened to the red sand expanse of the campground and mountain ridges beyond. Low, craggy trees and shrubs occasionally interrupted a landscape of red sand, dusty sage and desert wildflowers.

In the languid days that followed, I would shuttle bikers to departure points that had names like Porcupine Rim Trail. I’d decipher petroglyphs in plain view on roadside canyon walls, study improbable formations of towering sandstone from all angles, search endlessly for the next shot in my photo journal of this place.

It was easy to be caught up in palettes of sienna, russet, auburn and orange. Common weeds at first glance produced seemingly infinite variations of the color green, from dusty blue green to shimmery yellow green. The landscape that holds dinosaur tracks is also home to Podistera eastwoodiae, Oreovis bakeri, Besseya alpina, Saxifraga bronchialis and Carex perglobosa; ten imperiled plant species found only in this region. Each look through my lens, every shot I took framed the story of another world.

Coexisting with what met the eye, was that below the surface concealed until the moment it exerted a different kind of power: quicksand and currents of the Colorado River, the highly venomous protected midget rattlesnake, scorpions curled in the shelter of waiting shoes, compass cactus pointing southward, temperature swings of 70° in a single day offering equal opportunity for dehydration and hypothermia. The beauty that met the eye was more than matched by the enormity of what one couldn’t see in this land where certain soils aren’t dirt but living soil crusts, land still forming.

***

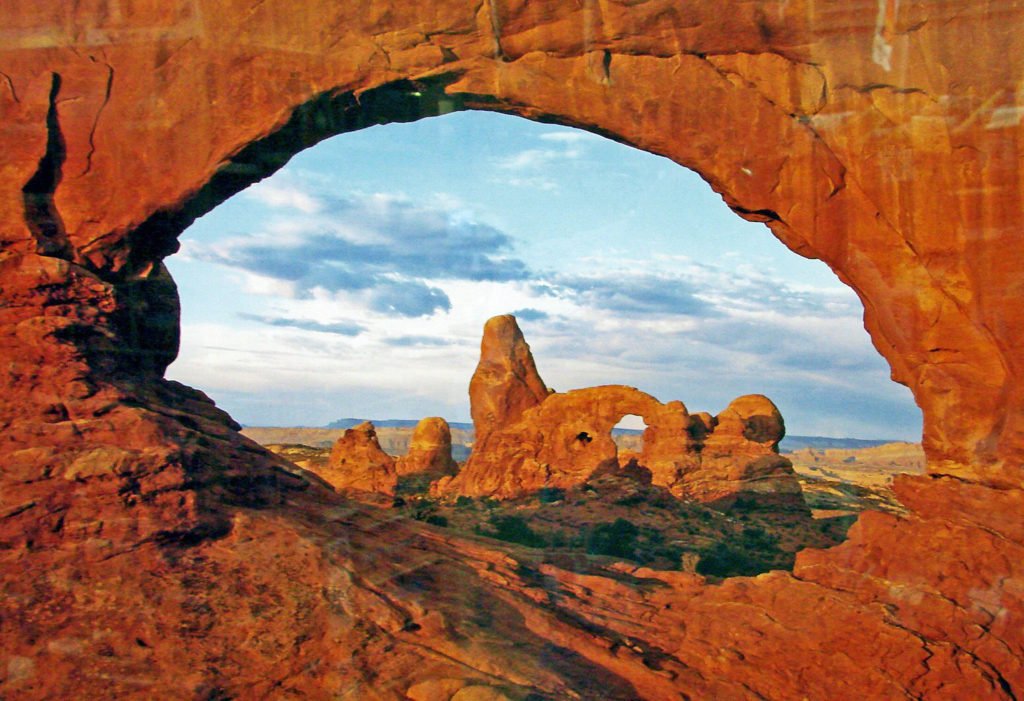

In the 11 X 14 photo on my office credenza, my husband, Doug leaned against red rock that rose in an imperfect arch around him. Taken a few short years before his death, it is a shadowy shot unlike the many blazing vistas tourists have taken at this place. His fitness and strength seemed to blend into the terrain, a formation himself against the rock, smiling his happiness there.

Now, I walked uphill with determination, feeling my tennis shoes and wishing for the steadiness of hiking boots. This was nothing, a climb that everyone and their kid was doing. I ran for a bit to see how I felt. Nada. I was frisky as a kid.

Suddenly the casual atmosphere changed. People above me peered through an arch. They spoke French—I understood but they didn‘t know it. He had a fear of heights but had scaled the slope to shoot through a layered rock arch. He was nervous as a pacing French chat, “Got the shot, got the shot can’t come down, will you run my lens up here, no I want to come down.”

She didn’t like heights either, held the lens standing very still and did not look up at him. Not at all.

I paused there. The rock was flat and dusty. Many people—families with small children—passed me on their way down the mountain. I went up, saw the precipice, turned around and walked down.

I wondered if avoiding the embarrassment of telling the story could propel me on path along the precipice.

I would have to tell Simon’s wife, Sally, who hung below with six-year-old Abby. I was certain they could not make it to where I was – a six-year-old for more than a few miles on hot rock, after all.

I went uphill again to the place where the narrow path rounded the mountain on the right, canting inward to the wall. The edge and vertical drop made me stop. I tried touching the rock wall to my right, small comfort that held me against the dizzying impulse to tilt in the direction of the cliff. All I saw was cliff. I turned around hiking all the way to the flat rock meeting ground where up-comers met the down-goers. I planned my story to Sally. Suddenly, there she was.

Six-year-old Abby said, “I have a plan.”

We walked the rocks passing many down-goers, soon reaching my point of not going on.

“Put on your hat Mary, turn the left brim down.”

“Watch my feet Mary, that’s the plan: watch my feet.”

Abby placed herself in front of me and I walked fifty terrifying paces along the path’s steep cliff, my eyes riveted to a pair of small pink Crocs. We reached the rock clearing, heard multi-lingual chatter in hushed voices punctuated by giggles and shrieks of children darting around the crowd. Delicate Arch rose before us, orange in the afternoon glow.

***

Just weeks before leaving on this trip, I had a dream that started in the family room of our home. Doug and I cocooned there surrounded by redwood, a river rock mountain cabin feeling without a fire lit in the fireplace. We spread ourselves on the big soft couch, draping limb over limb, dropping into the cushions, drifting into the sleep of utter contentment together.

Suddenly, I decided that I needed something from our bedroom and I walked the length to the other end of our house. Opening the hall door, I heard a sound. It was a sound I heard earlier in the day in the same part of the house. I searched the two bedrooms on either side of the hallway and inspected the closets. I gave up and turned to continue to our bedroom.

I heard the sound again and turned back, this time noting a sheet draped over the glass shower door in the hallway bathroom.

“Who’s there?”

The sheet moved in the way of someone trying to be still, not breathe.

I pulled the bathroom door shut and held it tight. I tried to scream but I heard only a gurgle before my throat closed. I tried again this time calling, “Doug…”

The prolonged syllable of my hoarse yell took me from sleep to wakefulness, the sound building as I became more alert.

I had again come face to face with my own paradox: through all finality a lingering disbelief that death could take my husband who was so full of life. His absence from what I did juxtaposed with his presence in thought and memory. I realized that for all the ways in which I embrace life, I will never say goodbye.

It was after this dream that I came to a decision about the urn in my bedroom. Doug expressed his own rapture on various hikes and mountain treks by saying to whoever was nearby, “When I die, I want my ashes scattered here.”

After his funeral, nephew Doug had asked for some ashes to scatter. I was not ready to part with them then. Moab would be the perfect place to start.

I drew the velvet sack over the pale marble urn, pulling its gold drawstrings tight and making a loose bow of them. A short drive took me and the urn I carried the through the double doorway of the funeral home. To the left of where I stood, incense and ethnic music wafted from a memorial service in another language. After a short wait and my explanation that I would like some of the ashes distributed into the six small boxes I carried with me, I heard the words.

“I’m so sorry, but the urn is sealed. If we’d known we could have…”

The conversation replayed in my head for the rest of the day. The following morning I called back, the good consumer ready to talk, “I’d like to speak with a manager.”

“The manager isn’t in but I am the senior person here. My name is Valerie. How may I help?”

“I came in yesterday hoping to have some of some of my husband’s ashes distributed from his urn into boxes. I was told it could not be done without shattering the urn because it’s sealed.”

“Yes, the cremains are handled according to…”

“I’m not implying that they were handled improperly. I didn’t know that I had to say I wanted to have access to them later.”

“They’re first sealed in plastic…”

“How was I to know? I was not advised that there were different sealing techniques if one wanted access later – if one had plans to…”

I was no longer the good consumer. Valerie heard my gasp as I stopped talking. Her smooth-as-an-undertaker voice took over.

“I’m so sorry. I lost my husband seven years ago and I truly understand. I can check with our manager and call you Monday.”

“I won’t be here. I was planning to take the ashes on my trip.”

“I’m so sorry. I will nevertheless talk with the manager and call you a week from today. Will that work?”

Her promise ended the conversation leaving me saddened that I would not fulfill some shadowy promise made more to myself than to Doug.

***

“Trrrrrroooeeeeee, Trrrrrroooeeeeee,” split open the darkness, shattering stillness.

“Trrrrrroooeeeeee, Trrrrrroooeeeeee,” lacy arpeggio through misty air.

“Trrrrrroooeeeeee…”

“Hah-hah-cah.”

“Trrrrrroooeeeeee.”

“Hah-hah-cah.” Bigger, definite.

“Rooo-upt.” A voice from a middle branch.

“Hah-hah-cah.” I pulled my sleeping bag to my ears.

“Trrrrrroooeeeeee.”

“Roo-upt.”

“Trrrrrroooeeeeee. Trrrrrroooeeeeee”

“Hah-hah-cah.”

It was like jazz. One instrument picks up on the fading resonance of another. The collection of them blend. Music runs it’s own course. When I listen to jazz, I don’t wish for earplugs. Instead, I drink in soul stirring colors and rhythms—ensemble launches my senses.

I cracked open one eye finding a sky the color of dark steel. The must of dew reached my nostrils through an open vent. I closed my eyes knowing when I opened them again, the sky would be a lighter gray glare with pinks and oranges creeping in bands behind clouds.

“Trrrrrroooeeeeee. Trrrrrroooeeeeee.”

“Wra-dooo,” a retort.

“Roo-upt.”

“Wra-dooo.”

“Trrrrrroooeeeeee.”

“Hah-hah-cah.”

“Wra-dooo.” The last word.

I wasn’t willing to give up sleep, and tried to hold onto the dream I was already forgetting. In its place now I saw huddled shapes, upright specters on craggy branches outside my tent.

“Morning all, morning all.”

“I need a worm, need a worm, need a worm.”

“Morning all.”

“Quiet!”

“Damp here…”

“Morning all, morning all.”

So far, each voice took its turn, a teasing conversation, a community. They seemed to have personalities. My imagination in full swing, I couldn’t get back to that dream. Maybe if I had earplugs…

I opened one eye finding the glare I expected.

“Hah-hah-cah. Hah-hah-cah.”

“Wra-dooo.”

“Hah-hah-cah..”

“Roo-upt.”

“Yaah-haak!”

“Hah-hah-cah. Hah-hah-cah.”

“Yaah-haak!”

“Wraah!” An outlier.

“Hah-hah-cah.”

“Roo-upt.” Still making nice.

“Wraah!”

“Yaah-haak!”

“Wra-dooo. Wra-dooo.”

“Yaah-haak!”

With each band of color and brightening cloud, the racket reached a more urgent cacophony of trills, nasal hacks, atonal spits, tenor urps, and belligerent retorts. With screeching crescendos, sound and light moved across the skies breaking stillness, demanding that everything be changed—all at once. And then, something monumental happened.

On the horizon, the round hazy light stretched its glow, repainting the sky, seeping warmth between cracks of night, releasing from dew a savory waft of cactus flowers, blue tinged shrubs and red sand dust. Everything became silent.

Breaking sunlight breathed a beginning, day in place of the dream I lost.

***

It wasn’t until I returned home and slid into the slick leather chair in the family room that I began my work. The chair was smooth, familiar. Outside the windows, a workman’s power washer sprayed debris off the flagstone porch. I breathed in the wet mist, and the green stuff—moss, a mix of leaves, the bay tree—I slid sit bones into sewn leather as I began a search to find out what 500 million years of geologic changes had made into the place called Moab.

Within minutes, I was reading about periods of time: the Pennsylvanian, Permian, Priassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous and the Tertiaries: 1, 2, and 3—each spanning hundreds of million years. My mind began to construct a time lapse animation in which ocean waters covering eastern Utah flowed out, shale and rock formed and layered onto one another, only to be covered again by ocean.

At one point deep dunes formed into Navajo sandstone.

In another era, fine-grained Estrata sandstone added its orange glow to the layers with hard white Curtis sandstone capping some formations.

The Wasatch fault lines that divide Utah slumped on the eastern face allowing sea waters to flood in yet again filling the region with sediment which become a riverbed, covered over in the pastel shale that now memorializes dinosaur footprints.

Yet again, eastern Utah became shallow ocean surrounded by western highlands and the Colorado Plateau. Toward the end of the Cretaceous era, the western edge of the continent began a massive uplift, the underground salt dome raising land. In fact, if one were to look beneath the shifting surface of the earth a thick but unstable of deposit of salt moved at glacier speed, the agent of change.

As the continent continued to rise, the Colorado River cut its course toward the Pacific Ocean, joining on its way with the Green River.

In what I imagine as a great heaving motion, the glacier of unstable Paradox Formation salt squeezed into a dome raising the rocks above it creating an anticline as the Colorado cut deeper between the rising rocks. Fissures in the rock over this salt dome formed fins and arches that, once etched by water, would continue to be etched by wind. At some point, the center of the anticline collapsed as the salt eroded likely dissolved deep into rock with the help of water running through fault lines at either side of the Moab Valley.

With time and image compressed in my brain, I paused my search; clear in my mind now the vast sweep of change.

Share this post with your friends.