The voice of the singer soared over the lyrics of the gospel choir that Easter morning a decade and a half ago. You plead my cause, You right my wrongs/ You break my chains, You overcome/ You gave Your life, to give me mine/ You say that I am free…How can it be?

I had plenty of reason for celebration sitting by my wife of thirty-five years, our son and his fiancée, and finally, my 88-year-old mother, all in a row. The exuberant parishioners were filled with joy, but I was still distracted with the questions of what a nice Jewish boy like me was doing at an Easter service, and would I ever find the sister I only recently found out existed.

At age fifty-nine, I thought I knew who I was. But that phone call on my mother’s birthday from the son of my father’s sister in Germany changed everything. My father had been deceased for a decade, and for some reason on that day after the phone call, I questioned my mother again about his life in Germany. To my astonishment, she announced that “he was married before and had a daughter.”

I remained speechless, particularly when she stated his wife and daughter’s names with such spontaneity that I felt the information to be true despite her creeping dementia.

My mind was swirling with emotions, and I couldn’t sort out a coherent response. Maybe I could find her. What was she like? How old was she? Would she be like me? What would we talk about? Would I like her? And finally, did she know about me? Questions consumed me.

***

My father, a member of a communist-oriented anti-Nazi group in his youth, was forced to leave Germany in 1936. He met my mother in Belgium, and they married in 1939 when he was thirty-six. When World War II broke out, my father was arrested as an enemy alien and imprisoned in an internment camp in Southern France. My mother, who was Jewish, went to find him. My father managed to escape from the camp and reunited with my mother. Always a step ahead of enthusiastic Vichy French officials eager to snag a Jew or a German communist, they remained on the run in Southern France for close to a year. To leave, they needed a Visa de Sortie de France.

They sat across from a French official with their big dossier, including an America visa. He looked at them. Then he studied the documents. He casually asked my father about his departure from the Gurs internment camp. His name was on a list. My father did not speak French. My mother, who was fluent in the language, was frozen with fear and could not talk. One false answer and they would have been interned and deported to a concentration camp in the east. My father, who at most knew only a few words of French, said mon femme est malad, meaning my wife is sick, indicating that was the reason he had left the camp. Besides using the present tense, he also used the masculine form of “my” instead of the feminine. The official simply smiled and pointed to the American visa, saying that they had the necessary document and that was sufficient.

Perhaps the reference by my father to his sick wife might have hit the official in a soft spot, since he was French—a small bureaucrat just trying to get through the day.

They traveled to neutral Portugal, where Jewish organizations helped with the expenses of their stay. On board one of the last ships to leave Europe under a huge Portuguese flag, boldly lit throughout the night to ward off German U-boat attacks, they arrived in Newport News in January of 1942.

I was born a year later in a tenement apartment in New York City. Now, with my mother’s memory gradually fading, I was intent on capturing the last remnants of my origins. My wife, Mildred, and I discussed these events at length. She was happy that I was discovering more of my past, but worried how I was affected. Finally, she took my hand between hers and rubbed my wrist with her thumb, a gesture that always communicated her strength and love to me. She smiled. “What are you going to do?” she asked.

“Find her,” I said, grateful for her support. “I have to find her.”

During the next several weeks, I visited and spoke with friends of my mother and father. They all knew about my half-sister and had always assumed that I knew as well.

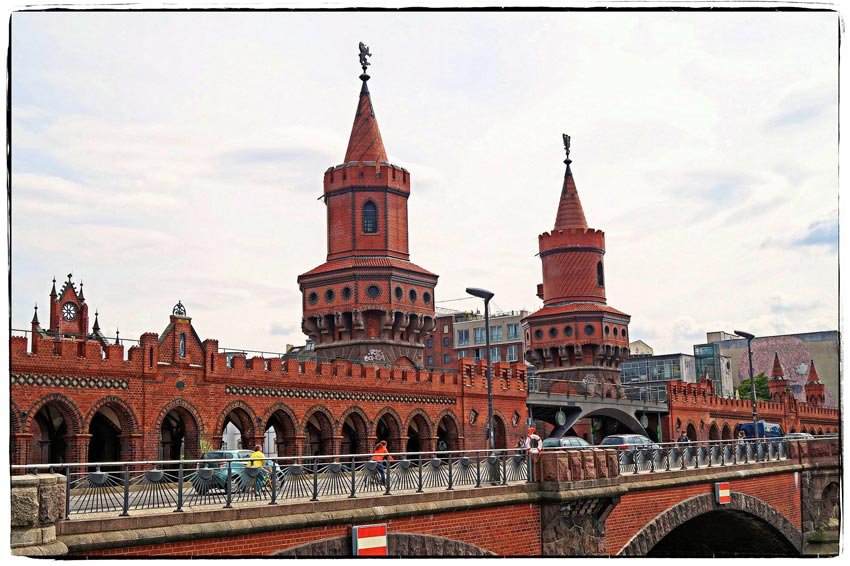

Once in America, my father closed his heart to his life in Germany and never mentioned it. He never adjusted to life in America and spoke only the bare rudiments of English. He became a chronic drinker. My mother always said he had left his heart in Weimar, Berlin. A place of avant-garde art, freewheeling sexuality, and extreme politics. Never going further than grade school, my father was a bona fide proletariat and not a coffee klatch Marxist. He lived in the physical world of tools and building, taking pride in working with his hands.

My mother, an educated lady from a well-to-do Jewish family, was a consummate liberal and voracious reader. She lived in the world of ideas, with an incessant desire to verbalize every thought that came to mind. Their differences, fashionable in prewar Europe, became more troublesome once they settled in America.

I inherited the need for physical work from my father and the desire to write from my mother. But after all these years to discover I had a sister, I wondered who I was. That photo of my uncle, the husband of another of my father’s sisters in Germany, whom I had never met, continued to haunt me. It had been sent to my father many years ago. Seeing my uncle wearing a Nazi uniform unsettled me. Little did he know when that photo was taken that he would perish in the wasteland of Stalingrad, that foreboding place that took an entire generation of Germany’s proud Wehrmacht.

Yet for me, as I reflected on that photo, he was the enemy according to everything I had been brought up to believe. Nevertheless, he was also my uncle, a man from my extended bloodline. Who was I?

In answering my own question, I didn’t consider myself Jewish. However, since my mother was Jewish, Jews considered me Jewish by birth, even if not by religious practice. The possibility of my half-sister being Jewish was a tantalizing thought which caused further confusion of my identity.

I’d been a member of this Black Baptist church now for more than seventeen years and felt comfortable. But our cultural divide was generations in the making. As I again focused on the music and the growing intensity of the worship, I thought of my wife, Mildred, who had grown up in the Black church. For her it was home, particularly during the singing. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, she played the piano in her African American Methodist Episcopal Church in Lockport, Illinois, where she grew up.

Her family was part of the great migration that had come from the Camden area of Mississippi during the 1940s and settled in a small town about an hour east of Chicago, near the Joliet State Prison. Her father often sang in the prison with a small church gospel group. There were five in her family. Sometimes they went without coal or skipped a meal. But they were always well-dressed, polite to elders, and self-sufficient. I understood her father as a Black man reflecting the culture of the AME Church. Like my father, he was a man of tools, trucks, and building. A widower when I first met him, he lived in a tiny house beside the railway tracks in Joliet. I would sit on the narrow porch with him, watch the trains go by, and drink pop. Never a beer, since no alcohol was allowed in his house.

There was a calmness about him which was unsettling to me in my younger years. I knew that he liked me to begin with just because of how I treated his daughter. I once heard him say to her, “Miiildreed, that man of yourrs is sure crazy about youuu.” He was right, and he’s still right today.

The next seven months were the most exciting in my life. I spent all my free time searching the Internet, the Berlin phone book, writing letters, and conversing with relatives. Leads came and went. Finally, I consulted an attorney who specialized in finding relatives in Germany. He referred me to a contact in Germany. “If she is alive,” the attorney said, “he will find her.”

Six weeks later I received an email with the name and phone number of my half-sister.

***

The first phone call with Anita was strained. She was expecting my call but was full of questions. She spoke English, having worked for American occupation forces in postwar Berlin, but communication was still difficult. After so much anticipation, finding her seemed a letdown.

What followed was an exchange of letters, each one telling me more about her life. She remembered my father, Max, and how he loved his beer. She also recalled my father’s request to divorce her mother, when he was about to marry my mother in Belgium. It was done by mail. Most appalling, she believed that our father had died in Portugal from tonsillitis. She had no idea that he had escaped to America or that I was born. It saddened me that he had never written to tell her about his life in America.

The search also enabled me to reestablish contact with my German family in Pforzheim and Freiburg. I knew that I had to meet Anita and my German family as well. A trip was planned.

We landed in Frankfurt and took a train to Berlin. And then the phone call to Anita.

“I come and pick you up at your hotel tomorrow, say at 10:00. Is that okay? I have a tour planned for tomorrow and several days. But we can talk more about it tomorrow.” It was very businesslike. Her voice was strong.

Somehow, I was expecting more.

The next morning dawned an ordinary day, just like any other. I saw a woman in a raincoat walk past the hotel and then dart back. It was her. She was short, her head buried in a big beige beret. Her rosy cheeks stood out to me. She looked spunky, full of energy.

“Yes, Peter and Mildred,” she said, extending her hand up high in a vigorous manner. I felt the urge to hug her, but then shook her hand instead. I then sat for a moment trying to take it all in, while she started with her tour book, the plan for the day, and how we should proceed. She acted like our personal tour guide. I understood this to be her manifestation of nervousness, to get down to business as soon as possible and gradually move toward more intimacy little by little. I had been the one to search her out, and she was keeping her distance till she got the range of me. But still, eight months of discovering, searching, and finally finding her, and it was all reduced to a quick handshake.

I noticed that she had a little tour book of the city which she said was for us. She also had two copies of three very neatly handwritten sheets of paper. The left column contained the bus, tram, or U-Bahn we were about to take, the middle column the action to be taken, such as “passing,” “stop,” or “walk,” and the right column the site we would see, such as the Brandenburg Gate, Checkpoint Charlie, etc. Then each site was referenced with a number which corresponded to a page number in our tour book. Mildred and I smiled at her efficiency.

Three days of touring Berlin followed. But it was the evenings together and a luncheon on the third day with her husband, Werner, when we were able to connect on a deeper level. Anita was a feisty woman who had endured great hardship, we learned. Relocated to the east portions of the old Germany (now part of Poland) as a teenager during the early bombing of Berlin, she returned in 1944 and worked for the Red Cross. She was bombed out of two apartments in close succession and lost everything. Along with her mother, she lived in the office where her mother worked. Meanwhile her childhood sweetheart was taken prisoner of war by the Russians. His army buddy killed himself to avoid capture by the Russians and the brutal treatment he envisioned. Anita endured the brutal Russian takeover of Berlin and Stalin’s order to rape Berlin’s women. Then, the end of the war and “difficult times,” as described by all Germans during that period of 1945 to 1947. Germans civilians starved. American occupying forces were ordered not to intervene. German soldiers became prisoners of war in Allied camps, where they experienced varying degrees of treatment from the good to dreadful. Of those sent to the Russian gulag, few ever returned.

Anita’s husband-to-be, Werner, returned in 1946. His skills as a mechanic enabled him to retrofit hundreds of Russian and German transport vehicles to assist a division of Russian soldiers to return home. It earned him a pass to freedom. Perhaps it was his pro-communist views and associations before the war that also helped.

And then Anita and her husband Werner’s life in Communist East Germany until the fall of the wall in 1989 was a life full of hardship. She and Werner never had children. I felt embarrassed when she told me, “Peter, you are fortunate that Max was able to get to America and that you had grown up there.” She said it with no spite, only thankfulness. A woman of simple wants, great admiration for humanity, who was thankful for the little that she had.

Little by little the connection between us grew. I continued to see my mother in her. It was as if my father had married a woman so much like his daughter. She was seventeen years older than I was, yet I could not relate to her as a sister, or even half-sister. She seemed more like my mother. In everything. Her values and her view of the world. So, the quest to find a sister brought me something else. But it took time for it to sink in.

A year later with the anniversary of this reunion approaching, I again looked at the photos and old letters belonging to our father Max to bring it all back in perspective. For the first time, the letters provided a glimpse of my father’s dreams when he first came to America. His letters were so expressive of his impressions of America and his plans.

And he wrote to his family in Germany of his little boy. He told them about me and what I was like. I never realized that he loved me that much. And that he was proud of me.

Then, it had all gone so wrong for him. Periods of unemployment, heavy drinking, and his verbal abuse of my mother. I had only known his defeats but never his dreams. Finding Anita, and gaining insight into his early life, helped me connect with him in a way that was never possible for me when he was alive.

Then as September 21st of that year approached, the date of my father’s birthday nearly a year after our trip to Germany, I knew what I had to do. I took the day off from work and asked Mildred to do the same, but without telling her where we would go. It was a beautiful late summer day with bright sun, but I was apprehensive and somewhat nervous of what to expect of myself.

When we arrived, we went to the office and I took out the note with the plot number. We meandered through the many lanes and eventually found the stone, small and flat with my father’s name and dates. I had never visited a grave. I had only previously been to a cemetery for a burial.

The hill is the same as the day we buried him, but at the same time, it is different. The trees are bigger, there are more rows of monuments, the season is different, and the smell of flowers is not as overwhelming as that day when his coffin was covered in lilies, an adoration casket spray in white and gold and green.

I just stood there for a while, not knowing what to do or say. I didn’t bring any flowers this time, feeling that somehow inappropriate for him. But as I stood, I started to think of him looking down on us.

I knew intuitively he would feel embarrassed by such display if he could see it. I had thought previously of some words to say, but they never came.

And so, I knelt before the stone and stared. With unshed tears, I simply thanked him for all the things he had given me that I wasn’t able to appreciate at the time. I told him I knew that he loved me, and I thanked him for the things that he had passed on to me. Then most of all, I thanked him for being my father and prayed to God for forgiveness for not being more understanding of the difficulties he had experienced.

But before getting up and leaving, I had to thank God for allowing me to experience this journey and reunite with my father. I had to thank him for his everlasting grace and love.

You plead my cause, You right my wrongs/ You break my chains, You overcome/ You gave Your life, to give me mine/ You say that I am free…How can it be?

And I find at least some of my answers there at my father’s resting place as my wife slips her hand in mine. I think of our son, his wife, the children they will someday welcome into the world. I think about who I was before we had him, all the things he will never know about me, the things I know about him he will never remember, the things his children won’t know about him. The chains that hold us back, the bonds that keep us together, and how each one of us works through that tangle as best we can.

Finally, I am ready to walk back to the car with my wife. There is only one word in my heart, but it is a beautiful word. Amen.

Share this post with your friends.

Peter. This is a very moving story. I appreciate the opportunity to get to know you and your history better. It’s been a pleasure to share writing experiences with you in Hillsdale as well