My wife wants me to write my own obituary. Write a draft in the third person and revise it as many times as it takes to produce a short, readable account of a life that will make sense, if at all, only in retrospect, when a theme or at least a pattern might emerge from the confusion of places I’ve lived, schools I’ve attended, jobs I’ve held. Put it in the safe with my other end-of-life papers, the insurance policies, list of passwords, living will, last will. And no, she stipulates, I may not make it a picaresque narrative. It has to be true to the selected facts and publishable in mainstream newspapers.

This is a checklist item: she aims to have on hand a proper long-form obituary of standard construction, opening with the date and city of my birth, identifying my late parents, listing some accomplishments, and closing with the names of my survivors, presumably including her own. Ever the practical one in our relationship, she will fill in the date of my demise and add a sentence about the final arrangements.

I’ve had some experience with the genre. My days begin with a ritual my father taught me. He’d sit down to his coffee, snap the newspaper open to what he called the Irishman’s sports page, and say, “Let’s see who died!” If I were promoted at work or received some little recognition, he’d say, “Well, there’s another item for your obit.” After he expired it fell to me to write his obituary for the Hartford Courant, and I discovered how little I knew of his life. It was a sketchy piece of writing, and even so I got the name of his high school wrong.

But I cannot honor my wife’s request. I’ve spent too much time reminiscing these past few years, recalled far too much, spotted the turning points, privately admitted the most regrettable decisions. I have seen how much depended on chance, the people I met, jobs I found, books I stumbled across, but I have also had to acknowledge my active part in this disorder. Artists and writers find universal truths in mundane lives, show us that ordinary people may say more than they intend and communicate more than they say, remind us that we might learn something startling about ourselves from just about anybody’s story. In the 1960s, when I foolishly hitchhiked between Hartford and Boston, the drivers who stopped for me unburdened themselves of worries they would not willingly confess to their oldest friends. But we turn to the obituary page for gossip, not insight—let’s see who died—and conventional articles about the recently departed lie ponderously on the artless plane of the trivial. In place of an obituary, I’ll put a copy of my résumé in the safe. My daughter, formerly a journalist and now a publisher, can consult it when she composes the obligatory article. My children went to the same high school I attended, so she’ll get that right.

***

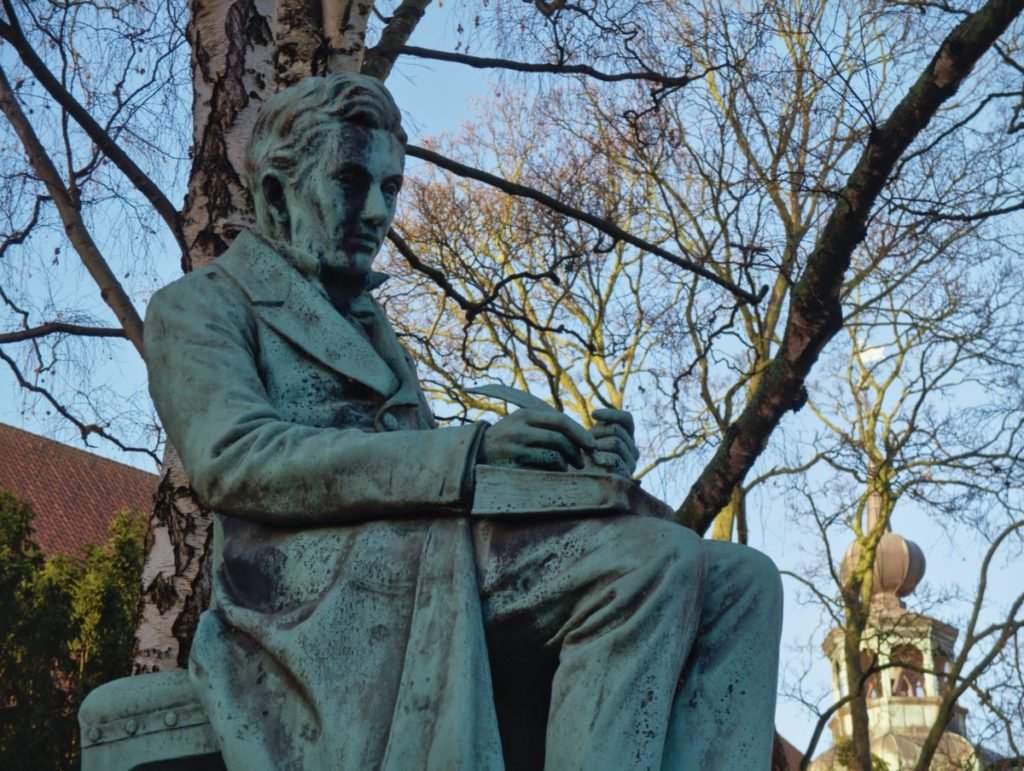

Søren Kierkegaard broke off his engagement to Regine Olsen on Monday, October 11, 1841, and never got over it.

He did not regret his decision, not exactly, not in the sense that, given another chance, he would have married her. He left Regine only because he knew she’d distract him from his vocation as a thinker and writer. The cost of his life’s work was a sort of voluntary bereavement, not just the solitude of any artist or writer, the normal seclusion of the contemplative life, nor merely the loneliness that afflicts so many men of my generation, the isolation we accept without complaint because it feels like our natural state: Kierkegaard sacrificed the love of a particular woman, grieved anew every day, and wrote irreplaceable books.

I am not like Kierkegaard. I do not have his gifts; I count myself lucky that I can read his work with some measure of understanding. Moreover, with a doctorate from a fine old European university and the thoughtless self-confidence of the young, I thought I could do it all, teach, write, raise a family. And I did, in a small way, for a few years. I taught philosophy and history at a community college, co-authored a textbook, made enough to get by with my wife and our first-born in a grand apartment with high ceilings and ample bookshelves, until my position was eliminated. It was the heyday of linguistic analysis, and there was no demand in the U.S. academic marketplace for a philosopher who had been educated in the continental tradition. My wife’s parents bought us a house near Boston and supported us while I went back to school for vocational training. I was functionally innumerate, yet, determined to make myself employable, I chose to specialize in finance and accounting. Playing to one’s weaknesses is a dubious career strategy. Still I persisted and, in the end, acquired enough proficiency in quantitative analysis to qualify for a master’s degree in business administration. No Kierkegaard, I.

While still in business school, I took a job as a consolidations accountant at a multinational manufacturing company near Boston, and upon graduating I joined a regional investment-banking firm in my hometown of Hartford. I soon left that outfit, however, for a position as Director, Cash Flow Forecasting and Liquidity Management in the treasurer’s department of a major insurance company. Never again would I have a title with so many syllables; right-justified, it occupied three lines on my business card. I loved the corporate culture, learned to manage a staff, saw myself as protecting the interests of widows and orphans.

The technical challenges were exhilarating. Every morning, multiline insurance companies receive a huge volume of cash inflows, chiefly policyholders’ premium payments, into their concentration banks. Those funds have to be invested quickly in the money markets before the highest-yielding securities are snapped up by other institutions. My team’s assignment was to predict the amount coming available so that the money market traders could start making commitments early in the day, and then to move the cash where it was needed to settle their trades. We analyzed historical data and developed a simple yet effective forecasting model with dummy variables for the month, week, day, and incidence of holidays. It told us, for example, how much to expect on a Wednesday in the third week of April, or on Tuesday after the 4thof July weekend, and with this information we enabled the traders not only to invest earlier in the morning but also to extend the maturity of their short-term instruments by several weeks. Soon I was hooked on adrenaline, addicted to the active life.

After a few years, however, the job became routine, I spent too much time initialing wire transfers and proofreading statistical reports, crises grew rare, almost welcome, and when they cropped up we knew how to handle them. I needed a new set of problems. I had completed a study and examination program for the Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation, and I wanted to work in the bond investment department. But my boss, and his boss, did not support any such transfer. “You have a job,” they said.

At an impasse, I finally accepted a position at another insurance company whose home office was farther downtown, and, after setting up a cash management unit, I became a fixed-income portfolio manager. I was responsible for $9 billion in securities backing the company’s guaranteed investment contracts (agreements under which the insurance company provides the purchaser with a specified rate of return over a stated period of time). It was a competitive market. The demand for high-yield assets impelled the business line to communicate directly with the real estate investment department and to press relentlessly, deal by deal, for an increasing concentration in directly negotiated loans to commercial real estate developers, some more or less honest, all looking for the main chance. I was not yet adept at corporate politics, and I did not handle the stress gracefully. Before long I was replaced as portfolio manager and put in charge of an investment technology group, the first in a series of middle-office assignments. When the commercial real estate market fell, the financially weakened company succumbed to a hostile takeover. I lost my job in the ensuing shakeup.

The pattern was set. Between those two companies, I had spent about a decade on the asset management side of the insurance industry. Over the next quarter-century, I worked as an investment professional at nine other organizations, from a big bank in New York City to a quant shop in Newport Beach. In most cases, I grew bored and moved on, took my restless mind elsewhere, while in others I left when business combinations disrupted operations. A friend said I had become a leading indicator. I probably would have left those companies anyway.

The one constant was reading. I read all the time, philosophy, history, literature (usually novels germane to my philosophical and historical explorations). Read at lunchtime when I might have been politicking, read all weekend when I might have been playing with the children, read late at night and on long flights when I might have been trying to sleep. I wrote a little, published unremarkable papers on Hegel, Nietzsche, Freud, Patočka, a solid piece on creativity in neural networks, then, increasingly, plain-language articles on financial topics that I could write during the workday; in truth, nothing memorable. I traveled on business, spoke at industry conferences throughout the United States, Canada, Europe, even spent a few weeks in Saudi Arabia and, later, South Africa. But mostly I read.

***

My father, for whom I am named, wanted to teach English literature, but the Second World War interrupted his graduate studies, and he never completed his master’s degree. He spent most of his career teaching sales techniques to life insurance agents. After conducting a week-long school in the Midwest, he told me that one of the men in attendance went to a corner of the room, sat on the floor, and, with intense concentration, tore his business card into tiny pieces. “I don’t know.” Dad shook his head. “It must have been some kind of nervous breakdown.”

But there’s more to it. Our work is bound up with how we see ourselves and imagine others see us. It is not the only factor that fixes our identity, but, unlike the accidents of birth, it’s one over which we have traditionally had some control. The right job lets us express our individuality, makes us feel competent, helpful, worthy. I have no idea what happened to the man in my father’s class, what brought him to that point, but his tearing up the card that bore his name suggests he was disintegrating. Not just ditching his corporate persona, he was shredding his own hopes and the burden of others’ expectations. Discarding—dis-carding—his very sense of self, giving up, bit by bit, the instinctive quest for satisfaction, recognition, approval that keeps us going.

I didn’t find a job that made me whole, but, with talk therapy and medication, I held myself together, and I was moderately successful in my financial career, earned enough to live well, saved enough to retire comfortably. I have all the time in the world for reading and writing. I spend hours in Charlottesville’s coffee shops. I’m in one now, surrounded by people, most of them women of a certain age with time on their hands this weekday morning. Many are lost in their screens, some wearing headphones, some tapping on keyboards; a few are conversing, not as quietly as they might. I have a cloistered space at home, a comfortable, well-lit study, all my books, Chopin softly in the background, but in the daytime, at least, I prefer to do my solitary work in the presence—if not quite the company—of other people.

Some days I miss the active life, fixate like a user. I long to belong, wish I were useful again, want to be somebody, the kind of man who wears a suit and carries a briefcase, goes to meetings, exchanges cards, gets results. But that’s unlikely to happen, and anyway—here’s the point—it’s not my calling. I’ve gone back to the original plan, stopping to think, learning to write, and, far from done, I’m just getting started.

Share this post with your friends.