Not until age seventy did I recall a place I’d never been—the Teenage Fair. Launched in 1961, it became a so-called “mini world’s fair for teenagers” which featured, according to one of its newspaper ads, a “battle of the beat, model cars, drag strip racing, dance contests, custom car caravan, surfing movies, Miss Teen International Pageant, harmony folk festival, movie, TV, radio, and record guest stars, judo, beauty clinics, thrill shows, photo and home movie expositions, fabulous fashion shows, dream cars of the future, bands and drill teams and nonstop record hop.” Also, someone told me, they handed out free samples of acne cream…which I could have used.

Vicky Danzig, one of Beverly Hills High School’s most stunning girls, didn’t need acne cream, not with her perfect complexion. Vicky was California personified. She turned up in my ninth-grade algebra class, glowing like an angel on a moonbeam. Even Mr. Brinegar, our teacher with a pitted nose and an old man’s raspy voice, seemed bewitched as she took her seat the first day of class. I was too shy to say anything to her. For the fifty-one minutes our class lasted, all I could do was gape.

“Tell Vicky,” my mother said that night at dinner, “that your father and her father are friends. They worked together.” They had. My father was an actor; Vicky’s, a director and later a producer. Frank Danzig directed my father in at least fourteen episodes of Your Voice of America, a dramatic series that told the story of Voice of America.

“Okay,” I said and kept eating the sausages and eggs my mother made.

My mother’s enthusiastic remark surprised me, because my parents had divorced five years earlier and she’d remarried two years after that. I didn’t think she would invoke her former husband in order to help me find a girlfriend, but she was developing a habit of encouraging me to date.

Hollywood and its whimsies were not my mother’s favorite things. Stan, her new husband, ran a company that manufactured business machines—a staid pursuit, a perfect complement to her personality. Bald and waging a constant battle against his weight, Stan talked with a trace of a New York accent and resembled the classic man in the gray flannel suit, not like my father—a tall, thin actor with thick black hair and a flawless baritone voice.

At least a week passed before I managed to approach Vicky, but before I could say, “Our fathers know each other,” the three-ring spiral notebook I always carried with one arm slipped and fell, spilling my three-by-five debate cards across the floor.

***

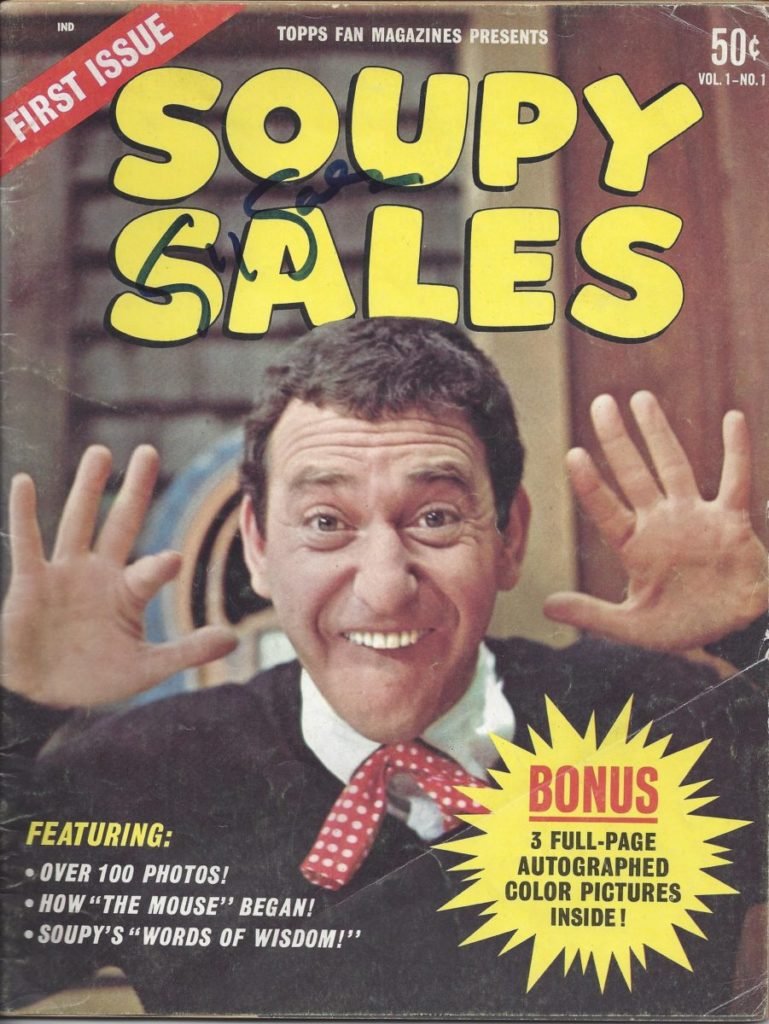

Around the same time, ads for the Teenage Fair started featuring Soupy Sales. “What will Soupy do at the Teenage Fair?” screamed one. “Will he judge the national open yo-yo championships? Or will he twist with Zelda Freed?” For a dollar seventy-five (plus tax), I could “come find out.” Along with almost all of Beverly High, I confess to venerating Soupy, a wacky, nutty comedian with a Stetson, a double-wide plaited excuse for a bow tie, and puppets that were supposed to pass for pets—Pookie, Hippy, and the black-and-white paws which represented his dogs Black Tooth and White Fang.

One day, on the middle tier of our school’s front lawn, members of the camera club nailed together a fake television set with an opening where the screen should be. They brought in replicas of Soupy’s costume and his puppets and then took pictures of us inside their ersatz TV, mimicking our hero.

Moments after they’d snapped my picture, Vicky appeared on the lawn. I caught my breath and struggled to think of what to say, but before I could form a word, a boy with a yo-yo trotted up to her. Yo-yos had become a fad that year, and this boy, taller and more rugged-looking than I, had mastered the art of turning his toy into a gravity-defying perpetual motion machine. He knew the tricks—walking the dog, through the tunnel, shoot the moon. This boy probably would win the National Open Yo-Yo Championships. I envisioned Soupy crowning him while Vicky looked on, her face full of pride. Vicky and the boy strolled away, chattering nonstop as he kept performing stunts. I rationalized my jealousy by telling myself that researching the year’s debate topic (federal aid to education) was more important than excelling at yo-yos.

At lunch a week later, Beverly High’s front lawn brimmed with yo-yos on every tier, yo-yos of all colors, some with stripes and some with lights. Standing in the center of the upper tier, coaxing his yo-yo through stunts I’d never imagined, was the boy I’d seen, with Vicky watching him nearby. This may sound naive but it’s true—the pain I felt gave way to the teenage optimism of the times, the certainty that good things would come my way. So each day, en route to algebra, I believed that finally, Vicky would talk with me, I’d muster the courage to ask her out, and she’d say yes. Surely today.

***

“Vicky’s parents have a powerboat,” my mother said over dinner one night in another attempt to spur me into calling her. She placed slices of pot roast onto my plate, followed by glazed carrots and spinach. Although this was a simple family dinner, she wore a V-neck sweater and a gabardine skirt, and she’d combed her wavy brown hair flawlessly. My mother was as good-looking as Vicky, even if you didn’t adjust for age. Stan had yet to remove his tie.

I perked up. Stan had a catamaran. Later, in bed, I daydreamed about seeing Vicky on the sea, far from her yo-yo boy. She’d wave at me, then yell over the sound of the engine, asking me to meet her back at the Southwind Marina in Long Beach, the closest anchorage to Beverly Hills. Maybe she’d talk to me in school because now we had two things in common: boats in the family as well as fathers who knew each other. But our boats never met.

***

Shortly before spring break, someone taped a poster for the Teenage Fair onto Mr. Brinegar’s bulletin board, and he remained too focused on his quadratic equations to remove it. There was Soupy Sales again, with Black Tooth’s paw caressing his face. “What will Soupy do at the Teenage Fair? Will he crown Miss Teen USA? Or will he feed a fish to the underwater frogman?” Silently, I sneered. I had more debate cards to type up and no desire to spend an hour riding a bus from Beverly Hills to the Hollywood Palladium just to enter a dance contest (which I’d lose) or stare at a bunch of wannabe Miss Teens (who couldn’t be as pretty as Vicky). Something, however, made me read to the bottom of the poster, the small print that identified the producers of the fair: “A Ross-Burton-Danzig production.”

Of course Vicky would visit her father’s fair. I imagined her there, gliding by the booths with the other boys and girls, all as lanky and lovely as she. My vision made sense. Vicky was exactly what the Teenage Fair was all about: music, beauty, weekends at the beach, easy nights along Mulholland Drive, and everyone dancing the twist, the fish, the mashed potato.

I wondered what, if anything, Vicky’s father told her about his event. Did he encourage her to go? Had he arranged a meeting with Soupy Sales? A dance with a celebrity band? Anything Vicky’s father dangled before her had to be more enticing than Stan’s boring gray business machines that went click and clack throughout the day.

The tardy bell was about to ring. At my desk, I turned in order to watch Vicky react to the poster, but that didn’t happen. She didn’t read the poster in Mr. Brinegar’s room because she never came to class again. “Her parents put her in a private school,” my mother said that night. She named an exclusive boarding school over twenty miles away, in Palos Verdes, a place unreachable for a boy without a car.

***

Vicky’s absence fed my longing. I called a top forty radio station to dedicate a song to her—The Mountain’s High by Dick and Dee Dee—but couldn’t get through. I listened to their disc jockeys, waiting for the advice about romance they sometimes offered. I thought of braving a bus ride to the fair, but I knew the laws of probability well enough to realize I’d probably never see Vicky there. Lonely at home one night, I used my index finger to write her name in a layer of dust on the top of my portable television set, next to its small antenna. Then, before crawling into bed, I added her name to one of my windowpanes along with a question: “Vicky, will you go steady with me?”

These telltale signs of my crush remained in the dust for the rest of the week, until my debate partner came over to play chess, looked through one of my windows, and saw her name.

“You must be really hung up on this chick,” he said.

“Not really,” I lied. I pulled the chess set out of the closet and started setting up the pieces on the floor. My partner, a boy as chunky as I, ambled about the bedroom as I did so.

“Oh no,” he said. “Vicky Danzig on the television set.”

I couldn’t offer anything beyond a stammer. Fortunately, my debate partner kept my crush a secret.

***

I got my driver’s license the following year, but never searched for Vicky’s school. I’d moved on, through another crush or two. Vicky and the Teenage Fair dropped out of my memory for half a century, but something about age seventy revived it, part of summing up a life, I suppose. That’s why I found her through a Google search and called.

Vicky (now Victoria) is a clinical social worker/therapist. She told me her parents had divorced while she was in school, which meant we’d actually had three things in common. Yes, she’d gone to the fair. She described it as “so California” before going on to say, “We were at the edge of the power of our generation, just before Vietnam. This was our last innocent experience.”

Victoria was right about our innocence. During one of the fairs, a teen radio station asked listeners to identify the biggest influences in their lives. According to a disc jockey, “The order was: God, disc jockeys, then parents.” On a Facebook page, someone wrote that at the 1966 fair, the Southland’s best-known top forty radio station displayed a monkey in a cage with a typewriter. Allegedly, they wouldn’t let him out until he’d typed the station’s call letters—K-R-L-A. Victoria’s father had created an event that captured California during its golden age, a time when the frolics as well as the hits just kept on coming. The Teenage Fair may have been one of the first events aimed directly at baby boomers who’d slipped into adolescence. And I had missed it. I wish I’d experienced that defining moment, but I was tone-deaf to the times, ignoring the good vibrations in favor of my debate cards, not dancing to the beat in favor of studying the Statistical Abstract of the United States.

I shouldn’t be so hard on myself. Only a few define a generation. Most of us don’t grasp the essence of the era we inhabit until it’s over. In school we’re trying to win the big game, get the good grade, find the first love. Later, we’re too busy working and raising our kids to go out there and join history, let alone make it. During the Roaring Twenties, how many people knew a flapper, frequented a speakeasy, or followed the Harlem Renaissance? How many, between 1966 and 1969, crashed in the Haight-Ashbury or attended Woodstock? I wonder how many lived—I mean really lived—the California dream as it was during the early 1960s, when it truly was a dream.

Share this post with your friends.

Hi Anthony,

How I love this article. I am Vicky’s younger sister, Priscilla. What a treat to hear all about your high school crush on my sister!

She was very pretty…and I longed to be just like her.

I did go to the Teen Age Fair and it was great fun. What I remember best was a phone booth set up with a microphone and sponsored by Laura Scudders potato chips. You had to go inside and crunch as loud as possible and it was measured by a crunch-o-meter!

This was just so much fun to read. You did a great job of recreating the era we were all living through.

Thanks so much…