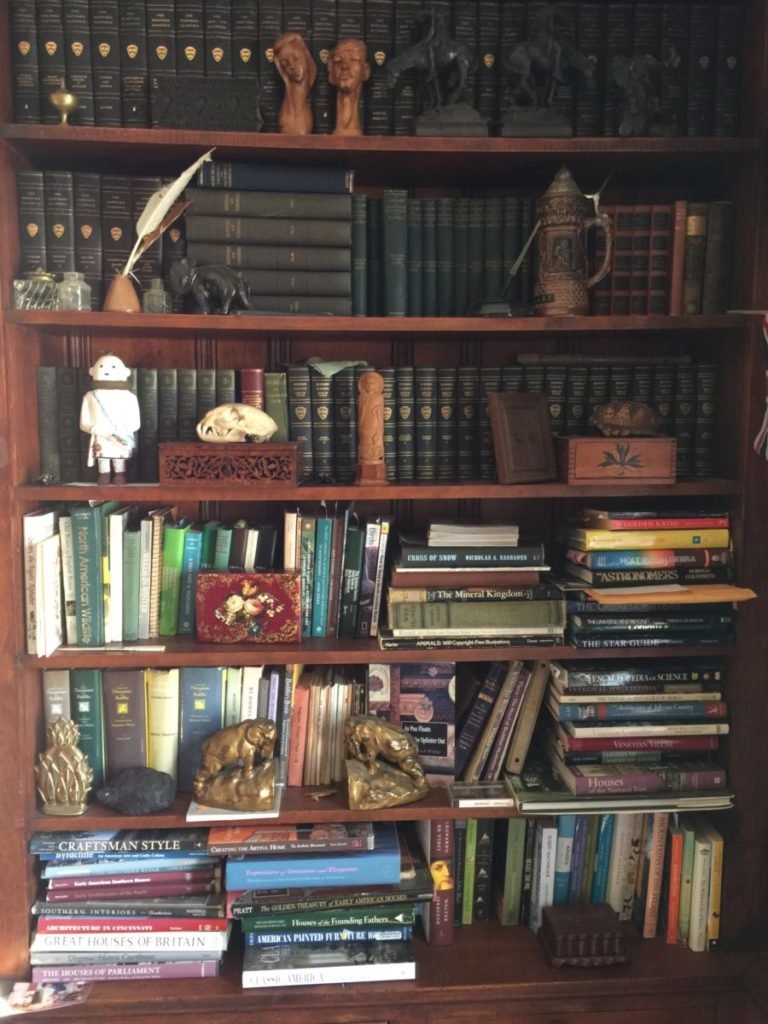

When insomnia provokes my wife or I to walk the footprint of our house, we sometimes end up at our bookroom. Bookroom is an idiosyncratic idiom of our family as my grandparents used the term, logically enough, for their room filled with books. When I was a kid it was the quiet room (Shssssh) with glass-doored cases, walls of tooled leather, slag glass lamps, and ‘oriental’ rugs. Our bookroom is not so different, though let’s substitute open shelves that, aggravatingly, are un-adjustable, walls of pine paneling, bright LED lights with inexpensive shades, and bare board floor.

Our books are the usual textbooks left over from college days, a few out of date reference books, the eclectic mix of history (my wife’s great interest), art and architecture (my great interest), science including nature identification guides, mathematics and astronomy, fiction (best sellers and classics), complete Shakespeare and Theravada cannon (in translation from the Pali). In short, the contents of the great minds.

In the cabinets below the shelves are more books, scrapbooks of foreign travels, photo albums, and notebooks of family genealogy. Stacked in front of these are towers of the recently read; not to imply a mere generic willy-nilly, they are laid in some unidentified bond of bricks. Periodically, at a glacial five or ten year increment, we cull those books we feel would have a better home somewhere else and donate them to the local library system for re-sale. Sometimes we regret this forced emigration.

Our books are not Dewey-decimal-ed or Library of Congress-ed, but grouped by broad subject area and/or by a guessing chronology. Some are even distributed to makeshift or purpose made shelves around the house: sewing books in the sewing room, poetry in the upstairs passage. Architecture, design and the craft of woodwork in the office where the desktop computer still lives.

But as much as the books, we cherish the bibelots, souvenirs, oddities, that have accumulated on shelf margins that intrigue our occasional visitors, grandchildren and even ourselves at times. I am reminded of those highly decorated sixteenth century cabinets of curiosities that held all sorts of conversation pieces and tokens of experience. On the shelves of my bookroom are natural specimens: hammer-halved geode, chunk of coal found in a window well, an Eastern Hercules beetle, small bird’s nest with horse hair, a bobcat’s skull, a crow’s skull. There are several woodblocks for printing patterns on fabric, a wedge shaped doorstop of rosewood, a dreidel, a fretwork box my great grandfather made for his fiancée, my great grandmother. There is a maple syrup spout (the sap bucket is in the corner), a rock climber’s piton, a small brass Buddha, End of the Trail bookends after James Earl Fraser’s original sculpture. Eototo, the Hopi katchina, presides over it all. Not to mention the clutter of inkwells, orthodontic castings, plumb-bobs, box turtle shell, small Union Jack, sea shells, prism, magnifying glass and dust. After all, cabinet originally meant a room and not a piece of furniture in the room.

All this to say, there is more to the seemingly passive activity of reading because most of the ‘work’ or ‘discovery’ has been accomplished by the writer. As an early teen I could never understand why my older, brainier, brother could spend a perfectly fine Saturday afternoon inside reading a book. The informed reader has to be both student sponge and fearless explorer in the ‘real’ world, descend the ivy tower as academics love to say. To paraphrase Zorba the Greek, What is the use of all your damned books if they don’t teach you how to live? I am not a gregarious sort with a multiplicity of social graces (as often I chide myself), but am endlessly fascinated by human behavior, by the complexity of the natural world, and by the profoundly simple; and with what happens inside the skull.

I noticed early on in the current pandemic, and probably you did too, that all the TV commentators had bookcases filled chock-a block with books in the background. All the walls of books looked alike. I know that you can order ‘books’ by the foot and by the color for one’s library. Then, maybe around month three, I began to notice subtle differences, a trophy here, a vase of never-wilting flowers there, books grouped by color, an author’s book in prominent front cover display. I began to realize, confirmed by an AARP magazine sidebar, that there is an art (or should be) to these arrangements: dos and don’ts, suggestions. This art of arrangement, the feng shui of books serves as a kind of proud credential, a badge of legitimacy. Admittedly, this phenomenon might just be present on the news outlets I watch. I certainly lament the educational divide in our country and am reminded of the skull and crossbones as the symbol for poison.

Share this post with your friends.