In the summer of 1967, the year of my high school graduation, the Newark, N.J.-adjacent town of Plainfield, where I grew up, exploded with race riots. I was in Washington, D.C. when it happened, working as a G-2 clerk-typist for the U.S. Post Office. I didn’t witness the events in my hometown, where an incident in a diner escalated into full-blown violence in reaction to police brutality against people of color.

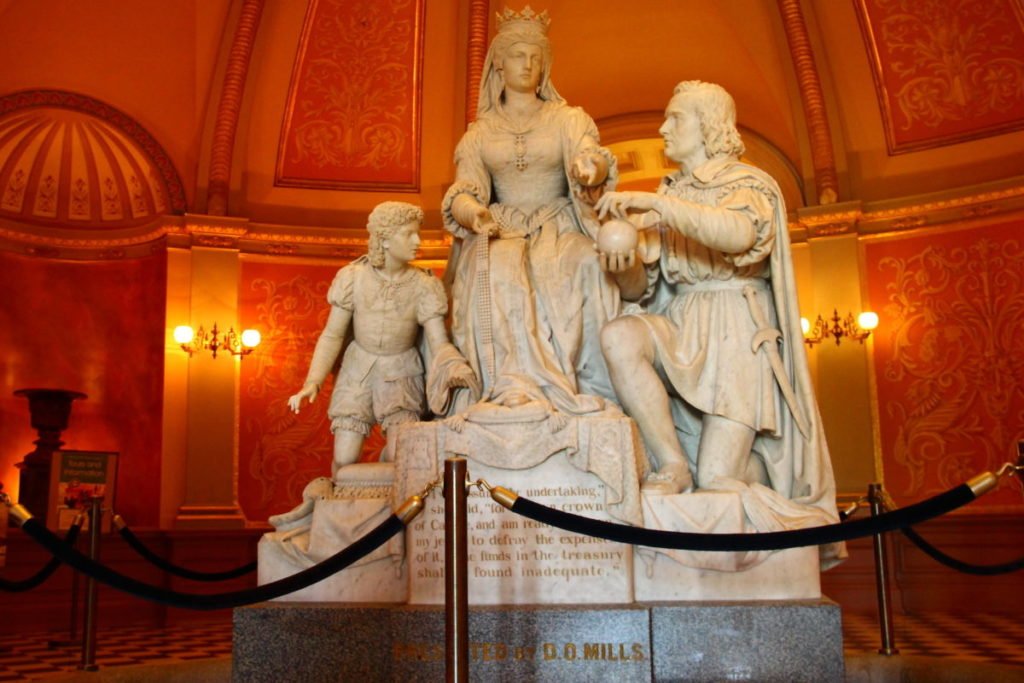

Fifty-one years later, as an officer handcuffed me for attempting to drape the crown of Queen Isabella of Spain with a foot-square piece of fabric, I wasn’t thinking about police brutality—I was advocating for climate justice, protesting the rape of the land and its inhabitants. As the CHP carted a group of us to the Sacramento County Jail for this act of “vandalism,” I was not afraid—I took it for granted that I was safe. It was 2018, two years before that statue of the explorer and his enabling queen would be removed from California’s Capitol building, thanks to protests all over the country that began with the police killing of yet another black man, George Floyd. Two years before private militia groups dragged protestors off the streets of Portland, Ore. Two years before a private citizen shot protestors in Kenosha, Wisc. Two years before a virus made it unsafe for anyone at all to be in a jail cell.

Statues that symbolize racial genocide are coming down, but the County Jail is full of prisoners, real people, not many of whom look like me, a seventy-one-year-old white woman with a twenty-four-hour criminal past. In my twenties, although I sometimes became the bad girl by using alcohol and making wrong-headed decisions, I was never arrested for drunk driving or carrying weed. In fact, I have only this arrest to date, and the case was dismissed.

On that June day in 2018, I pitched the bit of cloth at the statue and missed. A tiny Capitol Police officer pointed to the floor where she stood in classic TV cop stance, skinny legs apart and size five feet planted like cement poles, ten feet from the statue’s plinth. As she placed the plastic cuffs on me, she said, Am I hurting you? You have such tiny wrists.

Other than that exchange, the police seemed bored or mildly annoyed with my group, who were mostly old, mostly white, and unthreatening.

At CHP Processing, we had to take the laces from our shoes, which seemed impossible without the unfettered use of our hands. In the end, a redheaded cop knelt and undid my shoelaces. Take your wedding ring off, put your head forward, I am going to take your cap, he said, gently placing the items in a plastic bag.

When we were finally put into a cell, we became painfully aware that we weren’t at some book club or sleepover party, although we spoke of our pets and our nicknames, having been advised by attorneys that everything in the jail might be recorded. We weren’t to ask any of the women thrown in after us why they were there, but most of them, unprepared for their arrests, spilled their stories.

The current iteration of Jim Crow was in front of our faces. With no exceptions, the women who came into the cell that night were of color and wore the look of poverty. One of them was withdrawing from drugs — she periodically vomited into the waist-high partitioned toilet. A sobbing prisoner struggled to tell her family where she was, using a speaker-phone in the wall. She was “drunk and disorderly,” something that never landed me in jail—it took four hours of agitating for me to get arrested for an act of civil disobedience.

When I was seven, on a trip to Florida, I saw WHITES ONLY, COLOREDS ONLY signs. My mother said that day, when we saw a black man cross to the other side of the street, that he was avoiding being seen near white women, for fear of punishment. When I was fifteen, my family marched with Dr. King in Boston. I wrote in my diary: It was cool. Then we had ice cream. My understanding of racial justice has evolved since then, but I feel I must go deeper.

It wasn’t the two hours of sleep on a hard bench or going without edible food or palatable drinking water that struck me that night in Sacramento. As I threaded my shoelaces through the grommets of my Adidas at 4 a.m., I wondered when those women, who by accident of birth were much more likely to be incarcerated than I, would be released and what their lives would be like afterwards.

Now, fifty-four years after the riots in Plainfield, repression continues in Portland, Kenosha, and all over the country. History mustn’t continue to loop around on itself. After witnessing the injustice of the jailing of minorities firsthand, I feel strongly that white people cannot remain silent. We must join with those who are oppressed to shine light on racial injustice. We must do what we can to help end the continuing variations on discriminatory, cruel, and unusual punishment.

Share this post with your friends.