When my late husband set out to write his memoir he purchased Life As Story, by Tristine Rainer. He studied the book’s exercises and wrote in the margins. I want to read his annotations again. Feel the swoop of his pen; reacquaint myself with his responses to the memoir exercises. I have a distinct recollection of black ink on a cream page. Whole sentences, paragraphs filling the margins.

I pull the book from my shelf and peer inside. There are none of the annotations I remembered. Instead, a few underlines and a small circle within a wide arrow in the margins of a page—none of the annotations that I so clearly see in my mind’s eye. They must be in another book. I search the shelves. I pull out Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies. My husband underlined passages about lenses. The type of lenses Lumet used for different scenes, but no missing annotations. I scoured my shelves for the book that must exist.

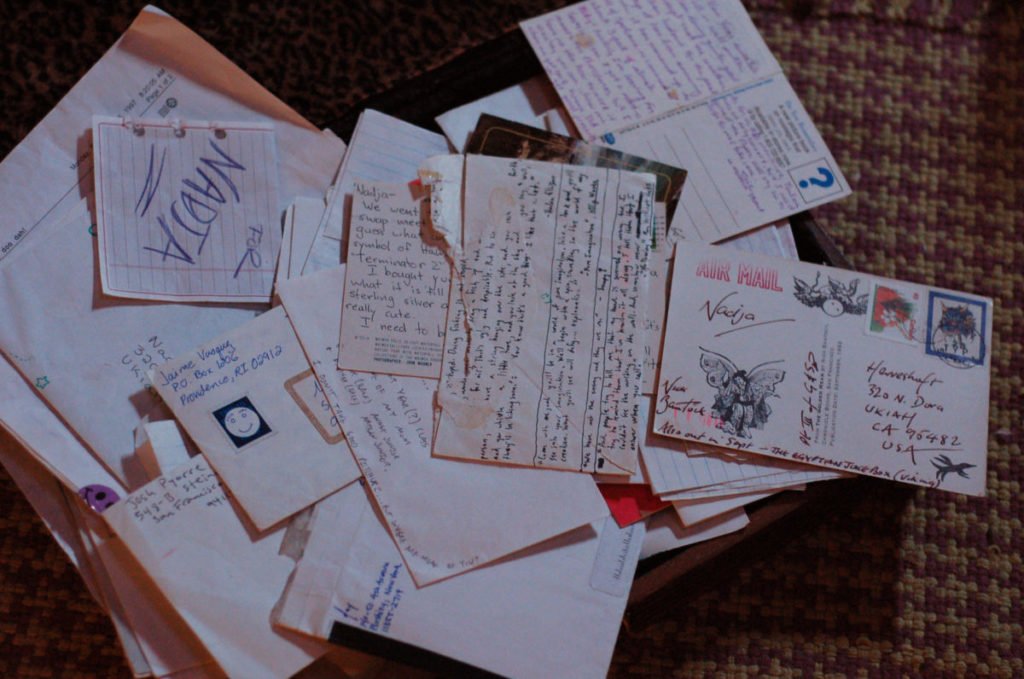

A faded green-gray folder stuffed with loose pages catches my eye. A folder with small white plastic hooks designed to rest on the iron rods in an old file cabinet. It sits at the far end of my shelf, ignored for years. I have no idea what’s in it.

There have been considerable books and articles written on how to eliminate clutter. Ann Pachett, in her essay “Practice” writes, “What I had didn’t surprise me half as much as how I felt about it.” [The New Yorker, March, 2021].

But Patchett did get rid of her clutter, lots of things in every room of her house. She threw or gave away. Nothing spared. Even her first typewriter.

It’s spring here in central Virginia. The bright green pastures, tulips, redbuds, purplish blue mountains, the frothy blossoms of the apple and pear trees. I place the age-softened folder in my lap.

First up, a friend’s twenty-year-old email, sincere and single-spaced, three pages. I hold it in my hand. Trash? No. Save. I’ll re-read later. Back into the folder.

Next, I pull out a purple sheet. At the top in large Abadi bold font, “The Contemporary Novel.” I glance over the list. The God of Small Things, by Arundati Roy, a beloved novel I taught in community college. But I have not read The Book of Intimate Grammar, by David Grossman or Human Croquetby Kate Atkinson. I must have dropped out of class. There are too many books on the list I may still read. Save. Next.

On a tattered envelope, a scribbled recipe for bourbon sweet potatoes. Trash. Wait. On the other side of the envelope—ink drawings of faces—my daughter’s sketches when she was eleven. Save.

L.A. Times article, “Investing Financial Information.” Trash.

Aha. Eighty-nine loose-leaf notebook pages. Years of writing workshop notes from my Santa Monica group held in the home of a workshop teacher whose husband left her because, she told us, he didn’t like her short arms. Really?

I sift through them. “Questions to Ask a Character” Assignments: Write a prose piece from the point of view of a moth. Did I ever do that one?

Feb. 15. Hand in story. Diary Form—’you see the progression of time and insanity.” I could use my mother. Save.

“Notice how characters fail to communicate.” Save.

A note I wrote in the margin about our workshop leader. A small-boned woman with dark cropped hair. “She turns the book’s pages, while she speaks, sliding her fingers up and down each page.” Why save that? Save because its on the same page as my observations upon seeing a Memphis friend who tells me the story of her mother’s Black servant whose doctor took her off of lithium and she threw herself into the river. I had forgotten that story.

A 1999 book review by Patricia Hampl in the Los Angeles Times, “In the Court of Memory: Why Augustine’s Passionate Quest to Know Himself and Praise God Matters.” I had scribbled in the margin: Fantastic! Ideas. I don’t remember them. Save.

A Magic Castle guest pass. Trash.

A decades old workshop critique of my short story, “Old River.” Definitely Trash.

A note left on my kitchen table. In huge red letters on a single sheet of paper.

Thanks for the Sequins!

Lynn

Lynn Redgrave, actress, mother. No longer with us. Canyon nights, crisp cold, our daughters in pink ballet slippers, eyes shining, hair curled, glittery and giddy in the Topanga Nutcracker Ballet.

I underestimated the emotional architecture of my clutter and overestimated my ruthless and unsentimental self. “Possessions stand between me and death,” Pachett writes.

I close the folder and slip it back on the shelf. If there is a time when I ramble through a folder of scraps and feel nothing, remember nothing—into the trash bin it goes.

Next time tackle the kitchen’s sticky spice shelves or the jumble of loveless shoes and boots in my closet. Or maybe by that time I will be a little bit crazier and pick up a scuffed boot and sing, “these boots are made for walking and that’s just what they’ll do. One of these days these boots will walk all over you.” There was that rascal back in Memphis.

Share this post with your friends.