Two “aha!” moments have erupted during my career as a fine arts photographer. But rather than lightning bolts from on-high, they arrived as a voice—my voice—exclaiming, “why not!” At each moment, my photography swerved in a new direction.

I began shooting seriously in the 1970s, alongside my career as a U.S. history professor at UNC, Chapel Hill. I was teaching an undergraduate seminar on “American Photography and American Culture.” Inspired by the work of Alfred Stieglitz, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank, I bought a Nikon FM, took workshops at Maine and RISD, and prowled the streets of New York, Paris and other cities. I was in quest of making photographs good enough to hang in art galleries. Alas, I produced pictures that were, at best, “interesting.”

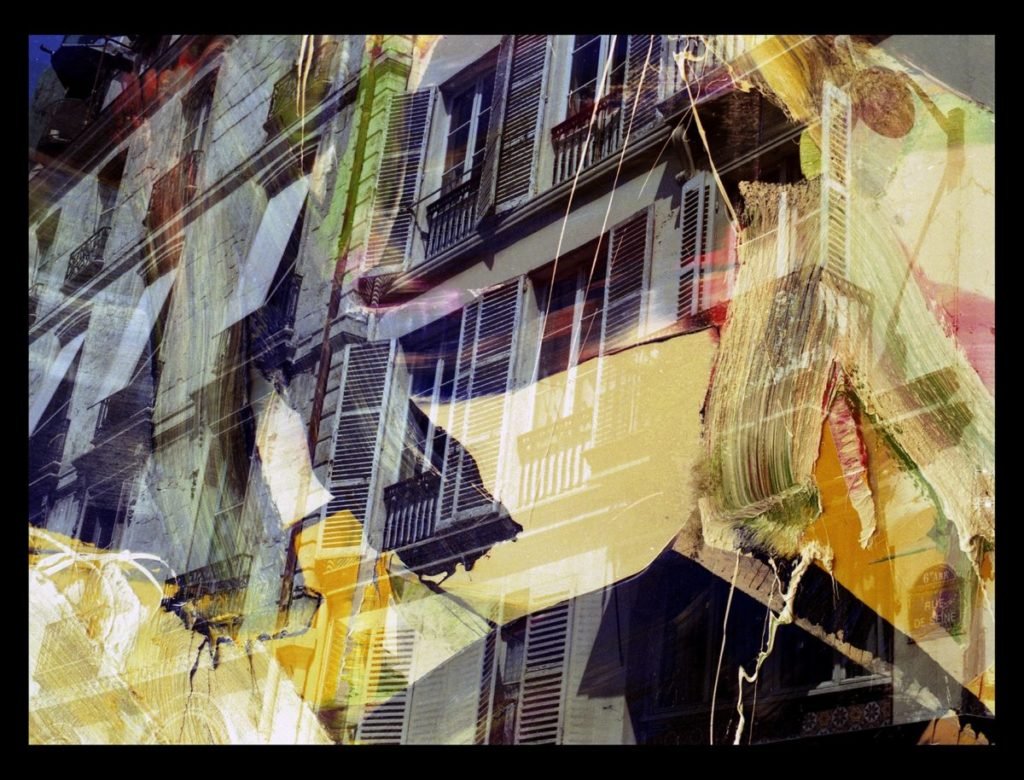

Then came the first “why not!” moment, one summer afternoon in 1994 on a street in Paris. As I shot those elegant gray Parisian shutters, I grimaced in frustration. My umpteenth photo of shutters. Surely it too would fall short of the artistic image in my mind. If only I could paint playful strokes of color on the print. But I was no painter.

Suddenly, I noticed the abstract landscape in a gallery window, a graceful patchwork of greens and oranges. Why not! I pushed the little lever on my Nikon FM to click the shutter without advancing the film. Then I shot the painting, a second image on top of the shutters. When I returned to Chapel Hill, developed the print, and saw the double exposure, I rejoiced. A painterly photograph! Just as a painting is made over time, so is a double exposure. It thereby entices viewers to ponder it a little longer than a “straight,” split-second photograph.

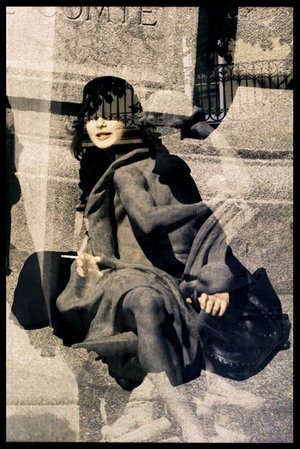

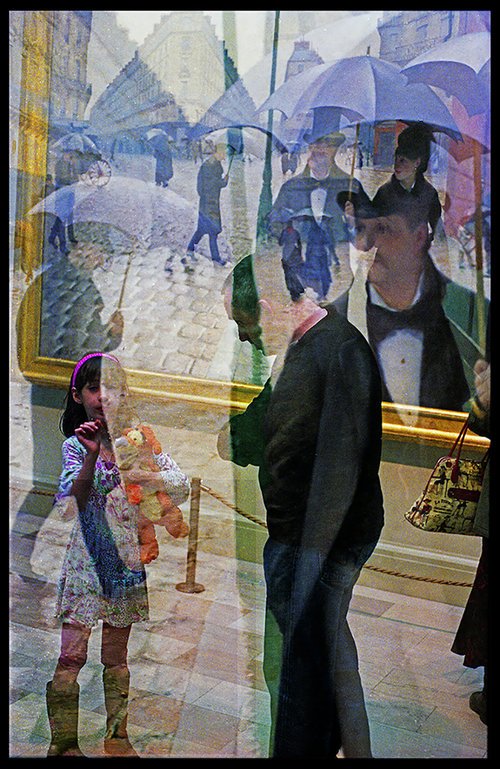

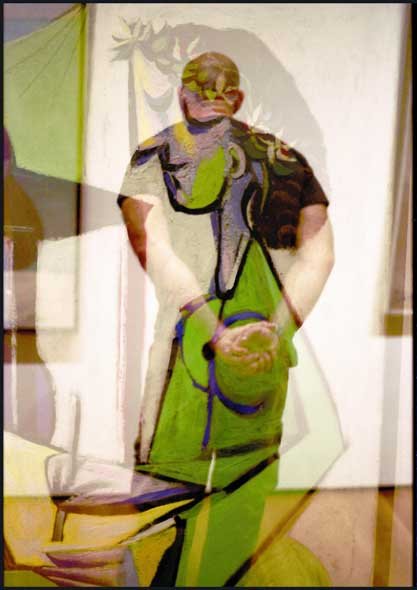

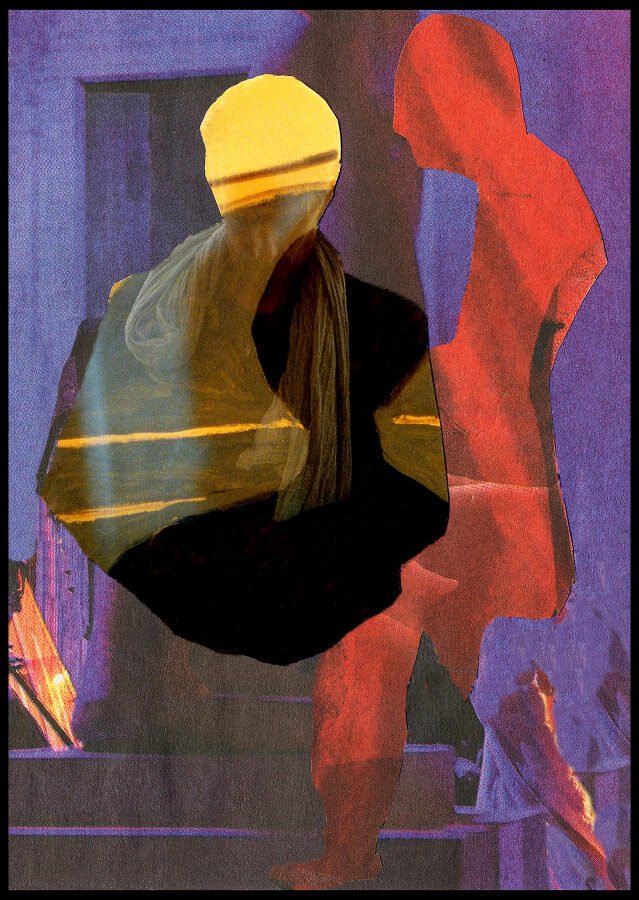

During the next twenty-five years, I concentrated on double exposures. I spent hours, especially in museums, shooting a person or scene, then looking for a work of art that would be the perfect mate when superimposed upon the image that waited on the film and in my head. If I was lucky, one or two out of thirty-six succeeded. The rest, murky or chaotic, ended in the trash. Double exposures are born in a marriage between intention and chance.

In Paris from the Beaubourg, I stood on the Pompidou Museum balcony and shot the predictable tourist picture of the skyline. But I wanted the untypical and unpredictable. So I walked inside and superimposed a closeup of an abstract canvas.

In Renoir in the Musée d’Orsay, the ghostly members of a boating party in 1880 mingle among a group of museum visitors in 2000.

By 2020, though, I realized I was repeating myself, imitating the best of my previous work. Self-quotation is not creativity. As I wrestled with this frustration, a more decisive frustration hit: the pandemic and quarantine. How does a photographer shoot new pictures if he can’t travel to photogenic places?

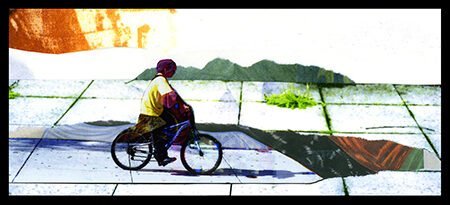

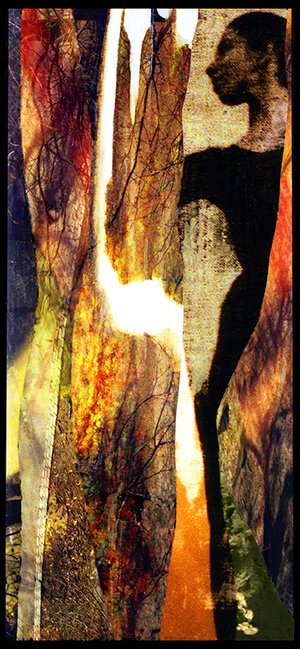

That’s when my second “why not!” moment occurred. One afternoon in my study, I began recklessly tearing up some of my photographs. As I combined the pieces this way, that way, they gradually, almost magically gathered into an unphotographic picture: a photo collage. I photographed it, tweaked it in Photoshop, and printed it.

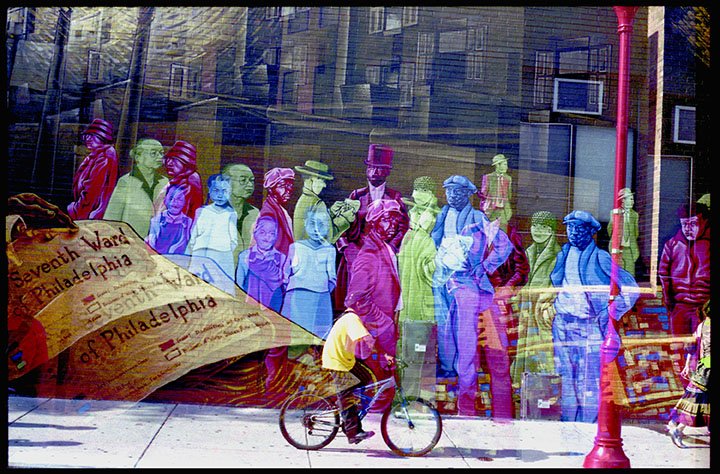

What fun! Consider Biking on South Street, (above) for example. I excerpted the bicyclist and inserted him into the surreal Sunday Morning landscape.

More impulsively, I excerpted the river of Biking in Central Park, turned it ninety degrees, and juxtaposed it with a woman from a different double exposure. She became Lady of the Island.

For the last two years, amid the quiet of home, I’ve been enjoying the serendipity of this latest “why not!”

To see more of my work, please visit www.peterfilene.com.

Share this post with your friends.