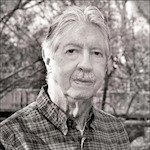

Margo Hamilton and Ron Evans share a studio and a passion for photography. At their studio at the McGuffey Arts Center in Charlottesville, Va. a variety of some twenty-five cameras are strung decoratively on one wall. Their work includes fine photography as well as portraits of family, children and silhouettes.

The two photographers met in 2009, Evans having moved to Charlottesville from Dallas, Texas where he had lived for thirty-five years. Hamilton had been living in Charlottesville for close to a decade.

A native of Little Rock, Ark., Evans remembers playing with his mother’s Kodak box camera pretending to take pictures when he was seven, eight, or nine. In high school and for seven years afterwards, he was a guitarist with a rock and roll band. He also worked in the repair department of a music store. There he badly broke his hand and couldn’t play the guitar. “I was depressed and thought I’ve always liked photography and I’m going to a camera store and buy a nice camera and I’m going to make photographs. I was twenty-two or twenty-three years old,” says Evans. He never looked back.

Evans used black and white film and had prints made at the camera store. “When I got them back I thought ‘That’s not what I saw. They didn’t know what I wanted.’ A friend at the Arkansas Gazette said ‘Ron you’re going to have to print your own work if you’re going to be happy.’”

So Evans bought an enlarger, trays and chemistry and started printing in his apartment kitchen. “I’d close the blinds and everything was dark, I’d print all night until the sun came up.

“I was always attracted to documentary work when I started,” he says. “My parents had taken Life Magazine and Life had some great photographers working for them years ago. Particularly seeing W. Eugene Smith’s photo essays, I realized how powerful photographs can be.” He also praises the work of Bruce Davidson and Mary Ellen Mark.

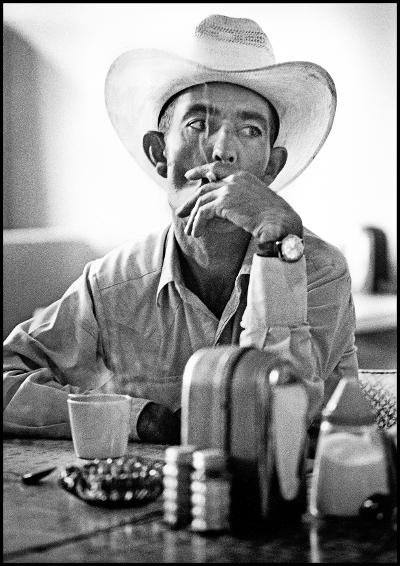

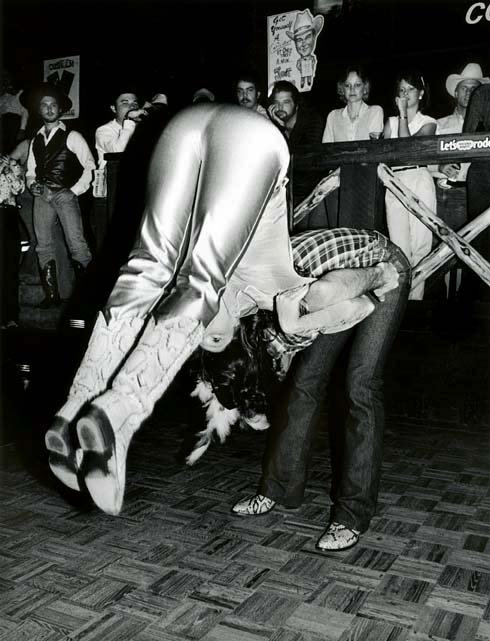

Evans went on to be an accomplished documentary photographer himself. He shoots mainly in black and white. Also a skilled printer, he worked for a color lab doing custom printing before becoming an editor for eight years with the stock house, Image Bank. “I looked at pictures every day and got paid for it. It was the best job I ever had,” he says.

Evans was later a staff photographer and stringer for a Dallas “underground” weekly and a “start up” newspaper, all the while continuing his own work.

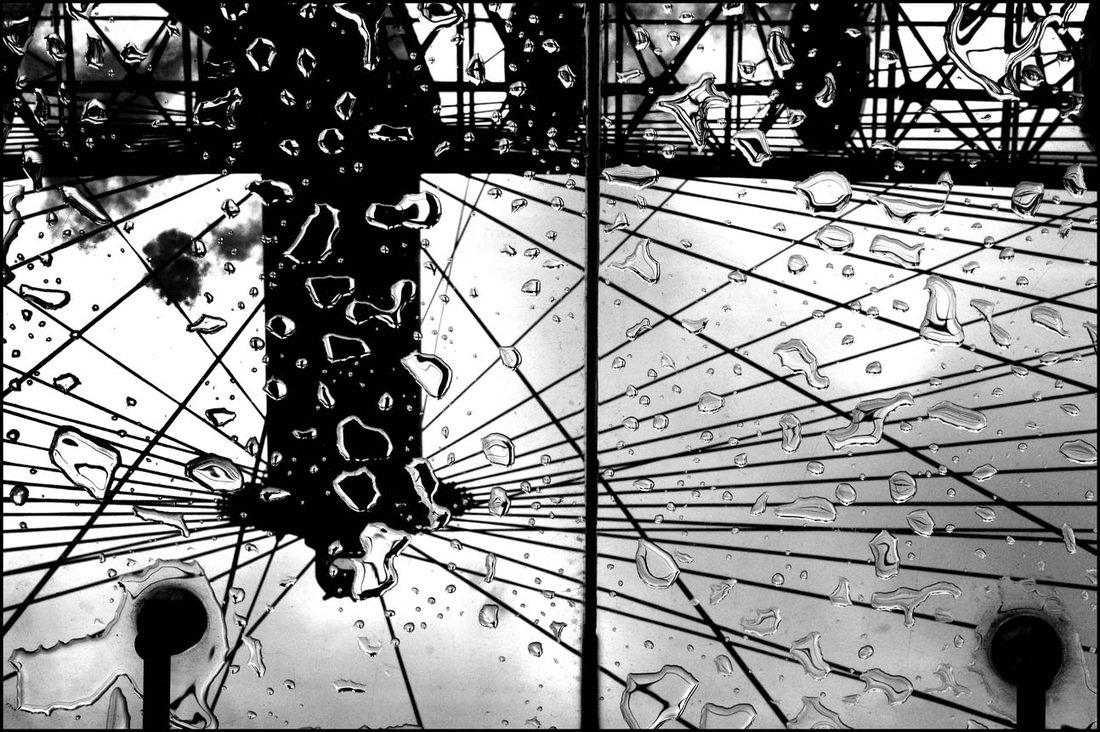

“I’m still doing documentary photography although I’m trying more abstract work during the pandemic when I was more in the studio than on the streets,” he says.

If he sometimes regrets being self-taught, Evans says, “On the other hand, printing your own work you see what works and what doesn’t. By making mistakes you learn a lot. I’ve certainly made plenty of mistakes and still do. I’ve been shooting over a half century and I learn something every time I’m out shooting.

“You just have to carry your camera all the time and you have to walk. If you’re doing documentary work, the best you can do is walk, see things.”

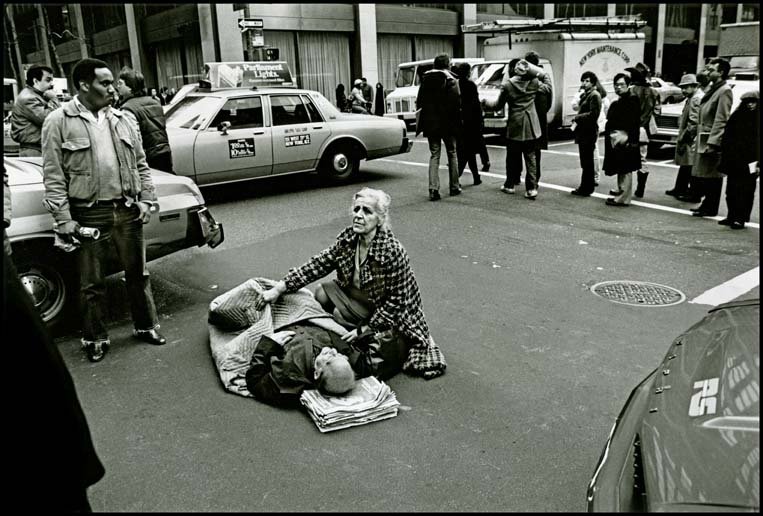

While walking with his camera in New York, Evans saw a man lying on his back in the street. “He had just been hit by a car and his leg was broken. His wife was leaning over him. Someone had come with a stack of newspapers and put it under his head as a pillow. After the newspapers, I shot that picture. You could hear the sirens coming. I always liked that picture. It’s something you couldn’t stage.” Evans’s photograph is now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas.

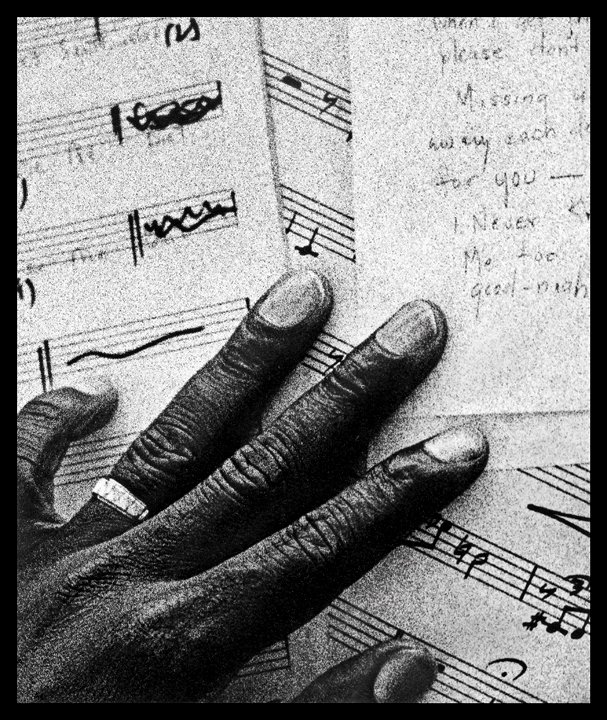

His closeup Jazz Concert was taken at Fair Park in Dallas where a band was playing jazz. “I was walking around photographing and saw this African American man playing trumpet. It was windy and he kept trying to hold the music on the stand he was playing. I noticed when he put his hand on the music it was just really great. I actually leaned over him when he was playing and shot that picture.” The photo is now in the Amon Carter Museum collection in Ft. Worth.

Originally from Oil City, Pa., Margo Hamilton remembers at eleven or twelve playing with her mother’s Brownie box camera, posing her Barbie dolls and pretending to take their pictures. “Barbie was my fashion model,” she laughs.

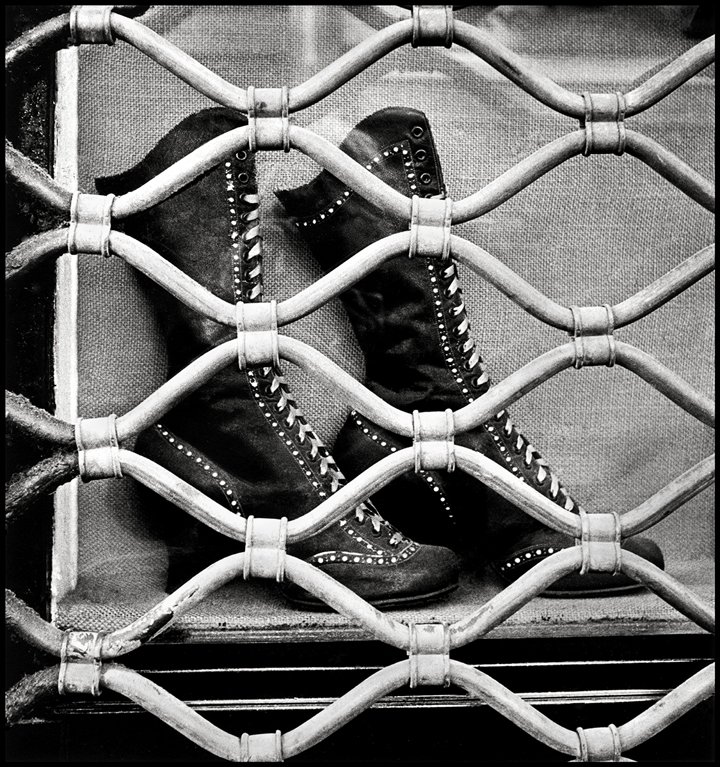

When married, she lived in Austin, Texas and traveled widely, taking mostly color photos of her husband and son and daughter at home and abroad. She continued, camera in hand, to shoot, always on the lookout for imaginative images—the curves and steps of the Petit Palais in Paris, the colors and textures of a canal lane in Suzhou, China.

Hamilton enjoyed photography but it wasn’t until fourteen years ago when she met Ron Evans that she took it more seriously. “I didn’t know what to do with black and white and Ron showed me how to do it. He introduced me to the darkroom. He taught me to read slides, negatives and pictures. He taught me how to edit and crop,” she says. “He showed me how to look at my photographs and made me realize photography was more than a hobby. I then thought of myself as a photographer.” She now shoots in black and white and color, depending on the image, and looks at her work with tutored eyes.

“My real drive in photography came in my mid to late forties when I met Ron. I didn’t know enough to look at other photographers and learn from them . . . even just looking at their pictures. Ron taught me that,” she says.

“Margo had been photographing for years when we met,” says Evans. “She already had good work. She just wanted to learn about black and white photography. And because I had a dark room here at McGuffey, I said sure.”

Hamilton now shies away from categorizing her work. “If I see a nice picture, I’ll take it. As a photographer I will not allow myself to be put in a box. I take pictures of things I like. I just consider myself a photographer.

“I look at all my pictures as memories and I like to preserve memories. When I’m photographing if it makes me happy, and I like it and think it’s interesting, I photograph it. Sometimes it is a little abstract—a door that is pealing off; sometimes it’s beautiful flowers or landscapes, windows, doors and cemeteries.” Hamilton also pursues family photography, often taking pictures of people from behind. “I feel it reveals a lot about relationships,” she adds.

One of Hamilton’s striking photographs shows two elderly twins in San Francisco. When Hamilton met New York activist photographer Donna Ferrato at the Look 3 photography festival in Charlottesville, she found they had both shot the twins. Hamilton gave Ferrato her print to which she exclaimed, “Awww! I love this picture. It’s better than mine.”

Today Hamilton and Evans both use 35 mm cameras and sometimes use 2 ¼ cameras for their larger negative. For the past decade they have gone to pre-schools and photographed the children outside in casual settings. They return thirty percent of their sales as a fund-raiser for the school.

Evans notes that everyone is now a photographer, using their iPhones as cameras. How then does a professional photographer stand apart?

“There’s a saying in photography: ‘Everything’s been photographed.’ So a lot of times when I see something that I’ve photographed before or it’s very similar, I don’t take the picture,” says Evans.

“I’m trying to make pictures that I’ve never made before which is hard to do. So with the abstract work, I’ve got a few that I think are pretty good.

“But as far as my documentary work, I do that because if I didn’t do it the photographs wouldn’t exist in the world. I made the picture; I took the time to do it. At some point, I may have a book of my work and seventy or eighty photographs that are worth looking at.

“I’ve always been a visual person. I ask what’s going to work today? If I’m working on a photograph or something I want to photograph that’s what I think about. As long as I’m alive I’ll probably be a photographer. It’s a passion. I will make photos until I can’t stand up.

“And,” Evans says, “Margo does great work, and in addition, she’s a great studio partner.”

Evans and Hamilton have exhibited their work together at the McGuffey Art Center. They will next show their photographs at McGuffey’s Members Show July 7 to August 13. See more of their photographs at www.studiozerocville.com.

—Written by Elizabeth Howard, Streetlight‘s Art Editor

Share this post with your friends.