As I Found It: My Mother’s House

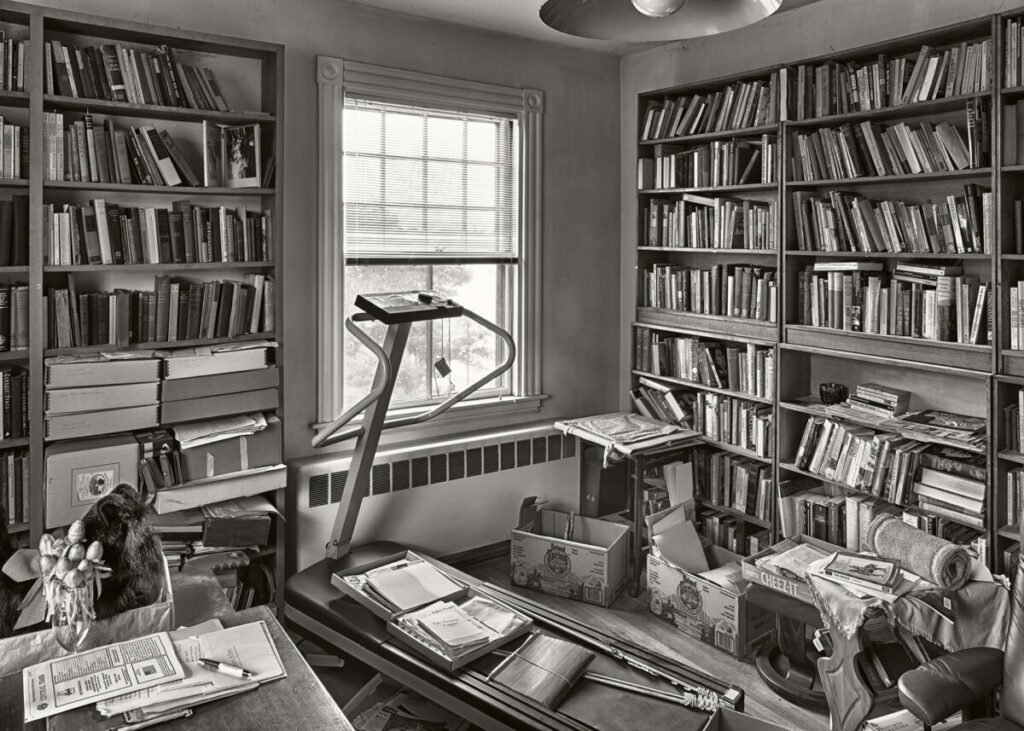

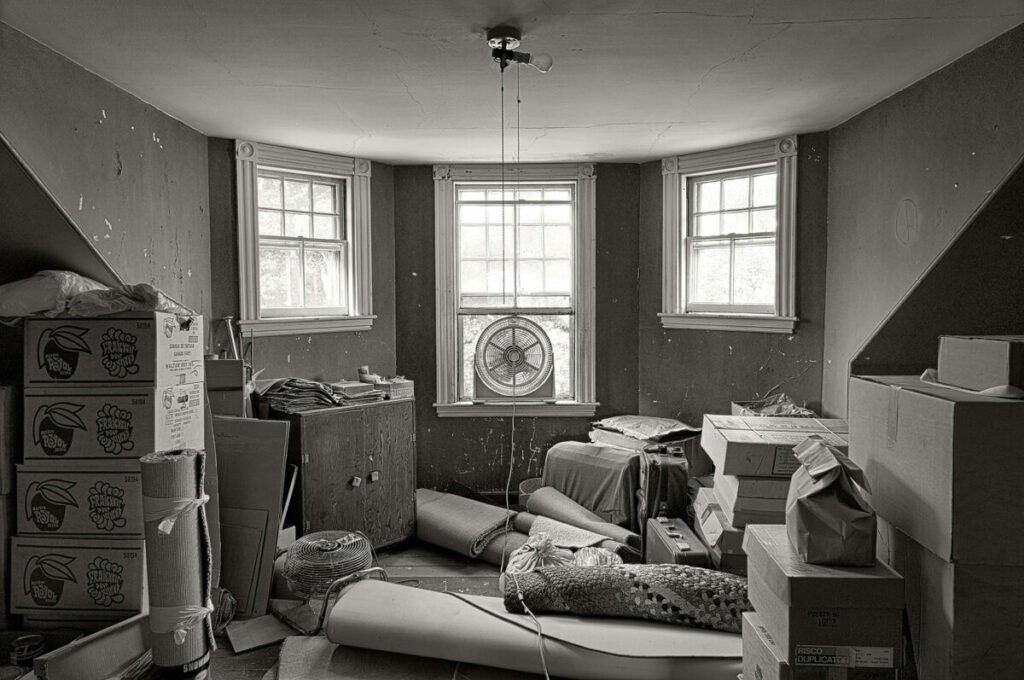

Sometimes I envy my baby-boomer friends for having lost their parents quickly. Mine left this life piecemeal. It took my father two painful years to die from cancer, and soon after, without her husband to moor her, my mother began her decade-long descent into dementia. When she could no longer live alone it fell to me to empty her house, a rambling, creaky Victorian on Boston’s South Shore that she had inhabited for over forty years. Paperwork piled high on her desk told a sad tale. Starting with her latest bills, cards, and copious notes to self I peeled away the layers, and at the very bottom found myself back at 2001. My mother’s life, in an emotional sense and as a realm she could successfully manage, had ended the year my father died.

My undertaking took the better part of two years. I plowed from morning to night through rooms gorged with decades of hoarding compounded by the Yankee custom of handing down meaningful objects.

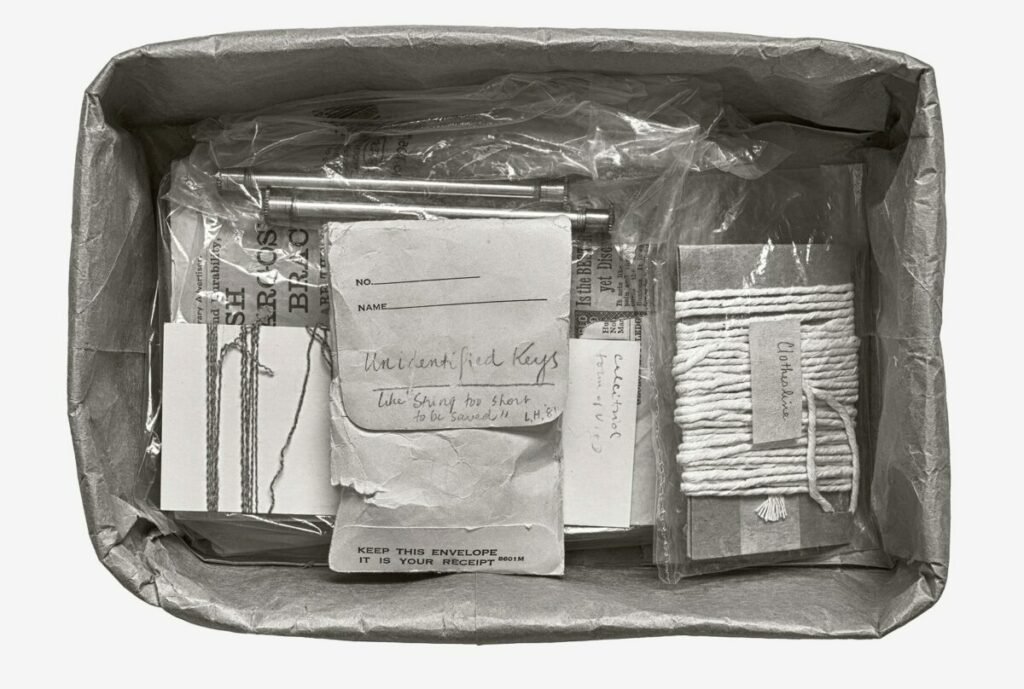

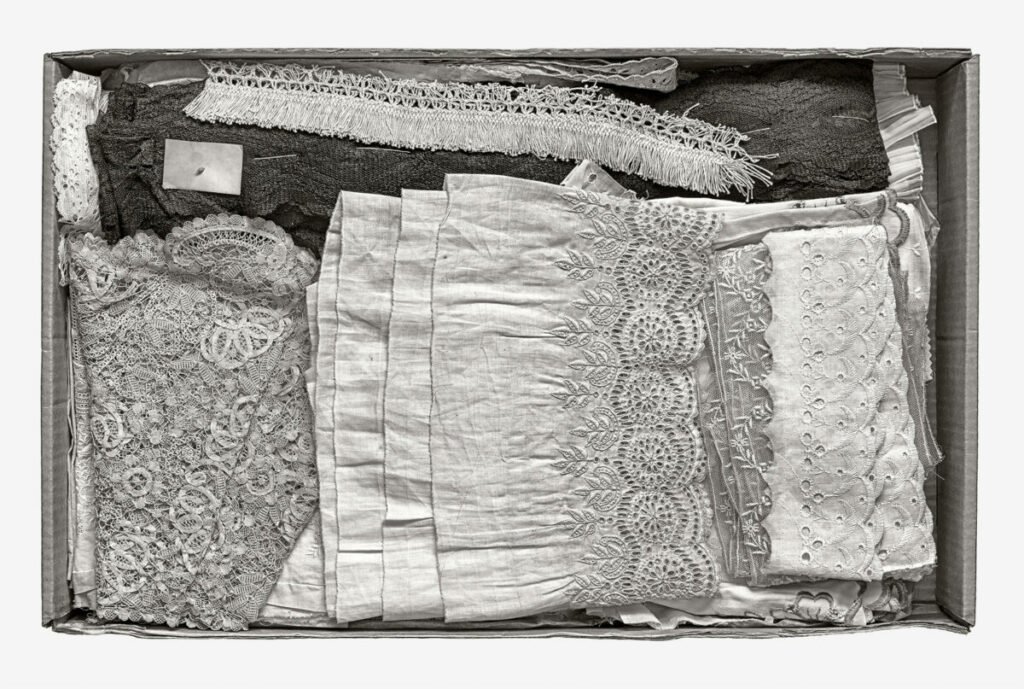

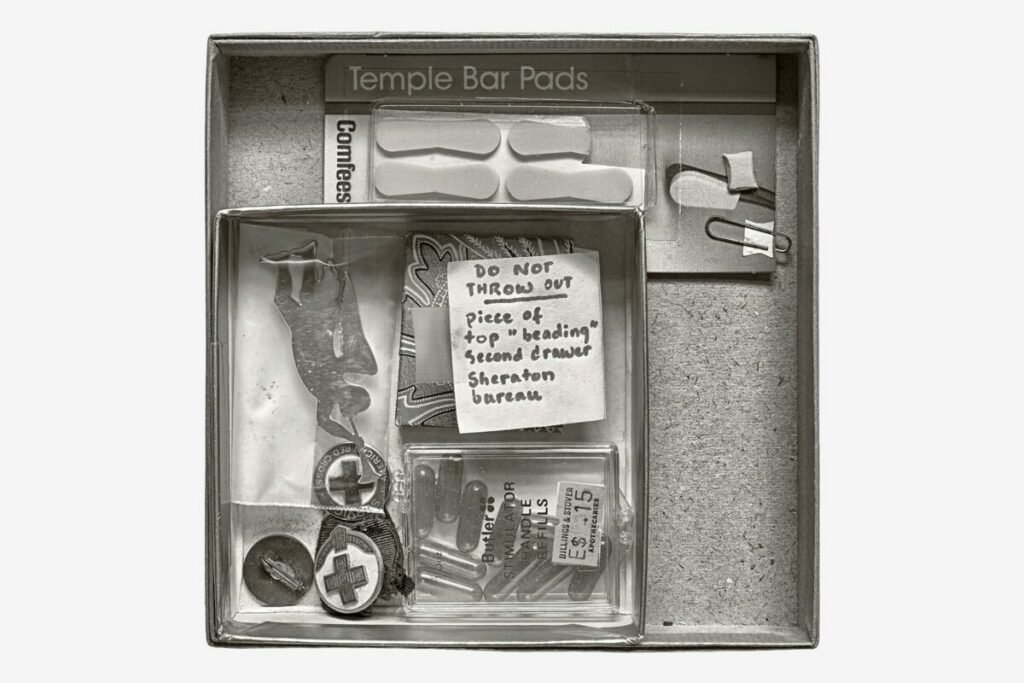

Much of what I unearthed was unfamiliar to me because it had been packed away for generations, sometimes a century. It ranged from unusuably practical to historical—from saved bits of string to the hand-woven wallet an ancestor had carried into battle. My determination to find a home for anything that had more life in it prolonged the job.

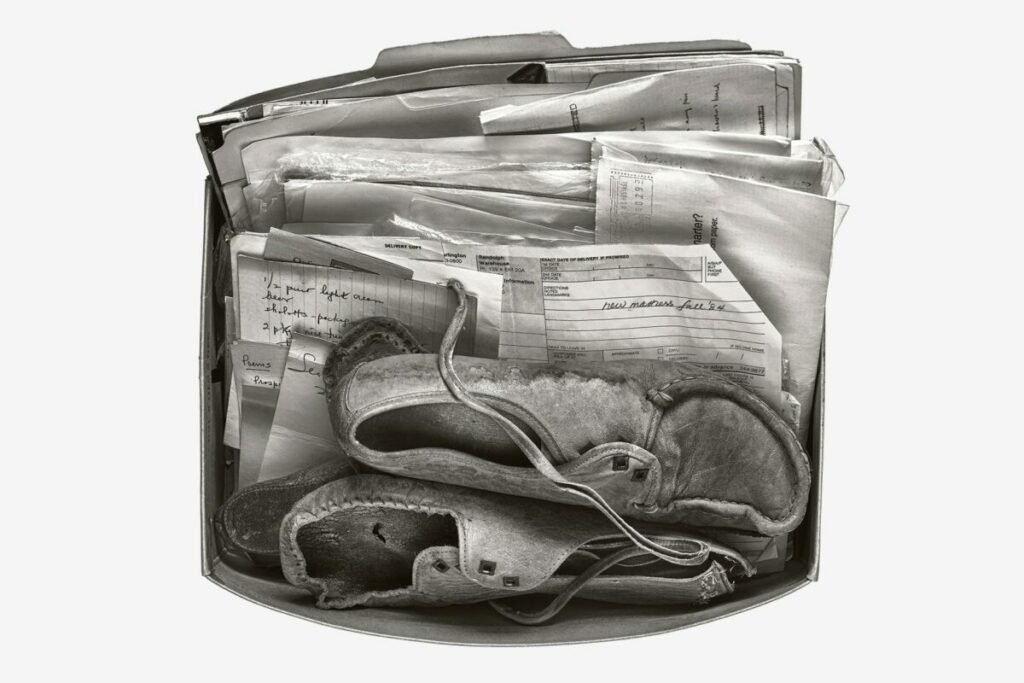

Beyond things in plain sight the house contained countless cardboard boxes. Clusters of smaller boxes were often nested inside the large ones, each containing an assortment of items. Some of these items were purely sentimental, such as the tightly coiled leash and collar with which we walked our short-lived childhood dog, loved most by my mother, already forty years gone.

Much of the boxes’ content appeared to be neatly ordered, but in ways that would have made sense only to my mother, which were no longer possible for her to explain. Boxes and their artifacts were often heavily annotated on index cards or Post-It notes, as if my mother wished to caption an entire life in the tiny, perfect handwriting that now abandoned her. She was obsessive-compulsive, a behavior that Alzheimer’s cured.

My task was the most solitary, emotionally difficult thing I’ve ever done, made doubly hard by daily visits to my mother’s “memory care” facility, where her personality and strength were ebbing away. Thinking it might mitigate my grief and loneliness I started taking photographs as I worked.

Along with increasingly empty interiors I began to photograph my mother’s boxed arrangements by the light of an attic window. I used a Sony Alpha A900 digital SLR and made the images black and white partly because I felt that the items’ varying colors often took the eye away from details I considered important. I used a technique called High Dynamic Range Imaging (HDRI), in which a series of identical frames are taken of the same subject at different exposures then combined digitally into a single image. This approach maintains tone and texture in both highlights and shadows, creating a delicate quality that’s akin to platinum prints. I also did extensive work in Photoshop to control the balance and contrast of the tones in the images.

Though these photographs are very personal, my hope is that they connect to the experience of anyone who has dealt with the decline of parents, and to the way in which that struggle revisits and reinvents the meaning of family. By inference I think it also addresses dementia’s destruction of identity and history. Yet I don’t want people to come to the work with too much information or too many preconceptions. I want viewers to be able to “read” the images’ content not only for what might be gleaned about my mother’s life and personality, but also for evocations of their own experience.

Share this post with your friends.