“Haze opened the extra door, expecting it to be a closet. It opened out

onto a drop of about thirty feet and looked down into a narrow bare

back yard where the garbage was collected. There was a plank nailed

across the door frame at knee level to keep anyone from falling out.”

( Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood, 61)

In our family album there is a picture of me taken by my Dad using his Brownie camera. The date is March 1959. I am standing in our back yard, about twenty feet from a garage that on its best day barely held our blue-green 1956 Chevy Special, “the old blue goose,” as Dad referred to her. That garage may or may not have been a fitting home for her, for as fitting goes, any passenger had to emerge from his or her seat before Dad backed the car in. No room on that side for anyone to get out cleanly, which for Dad meant not so much that the passenger might scrape a knee on the tin garage siding, but rather that he or she might scrape the car door.

Such was life with a man whose first new car would always be a sacred disappointment. No matter the washing and waxing, birds would besmirch its body as would little boys who liked to eat ice cream its interior, and wives who smoked and regularly missed the ashtray and soiled its textile floorboard. Its transmission was never the best, either. I kept hearing Dad complain about “the automatic choke,” yet another vaguery in a kid’s life, like that garage and its alleyway in.

Once, my grandmother, Nanny, told me that a strange man wandering in the alley by the garage decided to relieve himself in the weeds off to the right of its entrance. It seemed to me that I saw the refuse, two brown lumps that eventually turned white. I suppose these droppings might have been left by a stray dog, and I suppose that this memory might be only an imagining, because I can’t say for certain now whether I really saw a defecation there or not. But I do remember the sordid tale, for stories live beyond, and sometimes because of, our waste.

Inside the garage, there was a dirt floor with two rows of bricks marking a walkway from main door to back door, from which I’d watch Dad emerge every night after he nestled his car to bed.

In the photo, that back door is cut off, but had he framed the image more carefully, you’d see it, a five-foot door that Dad always had to duck under. The garage was built before Dad moved in, for this was my mother’s family house, the house she grew up in, and the house she wed him in. So maybe my grandfather wasn’t so tall, or maybe the tin designer measured incorrectly, or maybe it really didn’t matter, for anyone could get used to ducking his head, though my mother never had to back the car into the garage. Dad instructed her to leave it on the street for him to put up; he didn’t trust that she could back it into such a narrow opening without incident.

On what looks to be one of those bleak March days where even in Alabama winter still clings and spring is too cold to try, that photo shows me wearing a sweater over a white shirt buttoned to my neck and tucked into dark trousers. It appears that we might have been coming back from somewhere special, from downtown Bessemer or even Birmingham. Maybe we had been to the zoo or to a movie or shopping, with lunch at Britling’s Cafeteria. My hair looks just like Opie Taylor’s, combed down in front, bangs fringing front of my head. My left hand hangs by my side, and with my right, I seem to be gesturing or pointing. My fingers are splayed and maybe I’m in the motion of raising that hand to scratch my forehead, or to wave. I’m not exactly looking at the camera, and I’m not exactly smiling. I don’t look cold, either.

Why I’m standing in the back yard and why my Dad is taking my picture are things I’ll never know. It was such an odd choice: to take a shot in our bleak back yard on a cold winter’s day with a row of triangle buildings and a weedy alley in the background. It’s as if I simply wandered in to a picture that planned to feature our neighbor’s garage across the alley.

The grass is high in this image, which makes sense because in March the cutting wouldn’t have begun. Dad timed everything to the last detail, and lawn work didn’t begin until spring was official. Even then, he’d let the back yard grass go for two weeks, the front getting cut every Saturday. Eventually, he’d let me cut the backyard, but that would be another ten years after this photograph, the photograph that captured me standing in the tall grass—though you can’t see my feet–with the alley behind me, and in the distance two blocks away, South Highland Baptist Church, almost a ghost through the trees and late winter haze.

In this cloudy day’s image, I seem so alone, though I don’t look as frightened as I sometimes felt on such barren days.

Still, I can’t exactly read the look on my face.

What would make a boy almost three feel alone or frightened?

The man who defecated by our garage and might one day return to do worse?

The neighbors next door who a few months later set their house on fire, accidentally catching our house in the blaze and forcing us to live at the Holiday Inn for a month?

The hours my Dad spent away from us at work, especially from Thanksgiving to Christmas when he worked seven days a week and late most nights?

It’s so hard for a boy two or three-years old to understand these realities, the refuse of passing life.

***

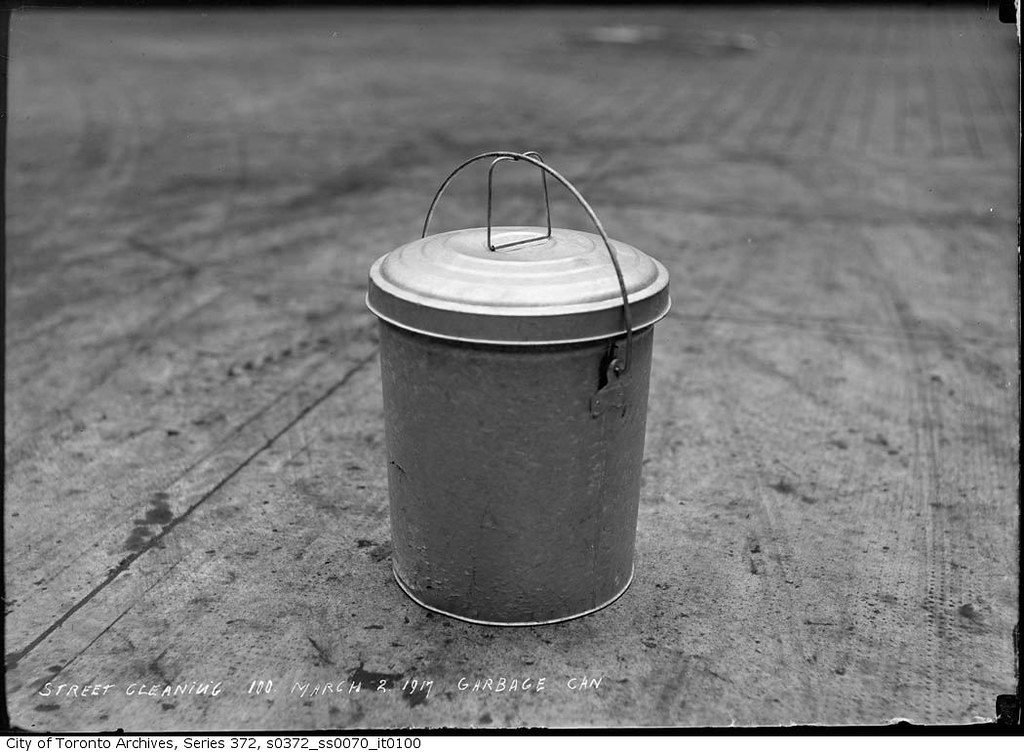

Just left of center in this picture is something that is too small to detect, too far in the background. It looks like a few small buckets and maybe a sign or an old chair, congregating for no apparent reason.

This is our garbage dump.

In reality, there’s a silver can sitting behind the other items, and a few years later, there will be two cans on a homemade wooden platform that would eventually have wooden guardrails built to secure these cans. Dogs freely roam our alley, and if there aren’t guardrails, or if the lids aren’t fastened tightly, the dogs will find the garbage, take what they need, and leave the rest (they’ll always, of course, take the very best). They’ll find easy access to not even spoiled food, because my mother hated leftovers, and even the Sunday roast, after it got turned into hash on Monday, would be dumped late on Monday night.

Living in the city, we all have back alleys where the garbage cans live, waiting on boys like me to carry out the night’s spoils. On Mondays and Thursdays, the big trucks would drive through these gravel and dirt alleys collecting everything, one slight, grassy patch acting as a median for them all down the line.

Fixed garbage pick-up times create more family drama.

Anytime a holiday falls on Monday or Thursday, the garbage men won’t come the following day to make it up, so we all have to suffer until the next regular pickup.

I say suffer, because my parents (both highly OCD, though I couldn’t have told anyone that until I married a psychotherapist, thirty-four years ago) worry about garbage collection. Imagine our Thanksgivings when my mother and my Nanny cook themselves silly. No garbage pickup for a week, and for many of those years, we have only the one can. After my brother is born, more than a year after this photo, the five of us collect and expunge more garbage than is reasonable. We get a second can, but if Christmas comes on a Monday, even two cans can’t contain us. My Dad feels this outrage particularly as if this, too, were some Communist plot against him, and fusses and fusses because inevitably the dogs wander by, and that turkey carcass finds its way in front of the garage on the workday morning after a beloved holiday.

He could have bought a third can or two larger cans. We could have been saved. But the platform and rails were built only for two regular-sized pails. It’s easy to lock yourself into such a guarded condition, though it’s beyond me now to explain my parents’ limited thinking, the limits they imposed on all of us but mostly on themselves.

In the time of picture I’m describing, however, I have no garbage worries. I don’t know that there’s anything about garbage to worry over.

Until, that is, I turn eight and my main household job becomes taking the garbage out at night, no matter the darkness, the weather, or that I am so scared of what might await me in the alley of my fears.

***

It was the long view, the view I took every afternoon and evening as I looked not out of a back door but from our den windows toward the back yard, the garage, the Baptist Church, and the garbage cans sitting by the alley.

I would wait by them every afternoon and during twilight times, staring at a point two blocks up, toward the street with that Baptist church, waiting to see my Dad’s car separate itself from the line of other headlights making a patterned glow, turn the corner of Dartmouth Avenue onto 19thStreet, and then enter our alley one and a half blocks later. He’d pass the garage before backing into it, always safely.

As I watched, I felt thankful that it wasn’t me trudging up the back path in the dark, though I made sure Dad passed the last gate before I left that window and stood before the side door as he mounted the back steps in the almost darkness.

A few years later, I was the one trudging up and down, into and out of that darkness, wondering if anyone was watching out for me.

There was no completely secure path to our garbage cans after a certain point. The redwood stairs, when freshly stained, were pretty and safe and had their own bare light bulb just above the back door. While this light helped me see down and back up those stairs, it also afforded me a too-clear view of the spiders that built webs above the door.

The steps themselves became a problem when the stain faded, the wood began splintering, and the entire staircase developed a palsy I’d sometimes see in Nanny’s friends. Nothing ever happened; no step ever gave way; no rail ever fell off after I grabbed it; and certainly the entire apparatus never collapsed. But it could have.

After the staircase, I’d make the right turn down our side yard to the back. The staircase light offered only enough glow to see the squared stone steps Mom had wedged there and the entrance to the doghouse sitting just under the staircase, where our Bassett-Beagle mix Sandy spent every night. My other nightly chore was to chain him there. I’d lead him down with the promise of a Milk Bone, the only way he’d follow me. We kept a blanket for him in his house, but I never believed it was enough because even Alabama has frosty winters.

At the border of the back yard, I’d have to feel my way through a dirt area. A few more squared stones helped me past the flowerbeds bordered by rows of monkey grass. There was no seeing anything clearly at this point. I could have taken Dad’s flashlight, but most of the time the garbage was too heavy and I had to use both hands. By instinct I’d weave around the edges of the beds and inching closer to those cans in the darkened yard.

It makes sense that garbage was collected in alleys out back. Garbage underscores our life’s daily waste, and you know how people are: we like to see how others live, what they buy and throw away. I like to track their cereal brands, the wrappings of whatever cake or cookie they “store-bought.” Garbage identifies us, tells stories about how cheap we are, how extravagant, and even how cruel. Dead pet birds and fish; old cat collars; toys and games. Maybe not even cruel; maybe heartbreaking and necessary.

We always lined our indoor garbage pails with the brown grocery sacks Mom saved. There were times when I’d have to carry the whole pail down because something wet would leak through the bag—coffee grounds, accumulated tea bags, wet paper towels from the tea or milk my brother and I would invariably spill at supper. When I got to the outdoor cans I’d have to put down whatever I was carrying and pry the silver lid off, because if I hadn’t closed it tightly enough the night before, or even if I had, Dad always checked the next morning as he opened the garage doors beside the bins, and tightened them with his Popeye forearms.

It wasn’t the tightness that caused me the problem, however. With enough muster, I could open them. No, it was the time it took to do so.

I’m sure that my whole journey never took longer than three minutes, half of which was spent maneuvering the garbage into those cans. It seemed to me that an entire episode of Gunsmoke or The Big Valley had run before I could get back to safety.

A heavy pail; fall and winter darkness when the back stair light covered only the first eighth of my journey; sounds I could never wholly account for; and the cans themselves, where as I was fumbling with lids and dumping, I was at my most vulnerable.

Between the end of our yard and the alley, there was also a gully, or as Dad called it, our “ditch,” which ran the width of our property. For some, this might have been extra insurance against any predator or enemy. For me, it was just another place for something to hide—some being to plot against me, to take me. In college, when I read Faulkner’s That Evening Sun, where the Compson children talk about seeing “Nancy’s bones” lying in a ditch near the house, I remembered our ditch and the foreboding feeling I had.

The chill of old bones amidst childhood refuse.

Though nothing bad ever happened to me, the occasional spider web notwithstanding, every night there was the potential: a stray dog or rat; a bag tearing on the way; a man looking to defecate somewhere close by.

Making it back inside each night, I’d try to forget for those few hours the journey I’d have to make the following night.

The front yard of our house was a different story; out there, no matter the season, I’d walk Sandy after supper, making sure that he never defaced Dad’s lawn. Our front porch light, aided by the streetlights at the corners, comforted me. And no one that I ever heard of had defecated in the front yard. But on some nights Sandy needed more distance, more exercise, and his own comfort spot to do his business. He’d lead me to the corner near 18thStreet, where there were ten-feet high shrubs extending from the McEniry’s house through a vacant lot. I was sure someone was hiding in these shrubs, waiting for me. In the dark.

***

All of these memories are sixty years old, dating back to the moment Dad snapped that photo. It’s been twenty-two years since I last stared out of those back windows, and longer since I had to escort our garbage to its semi-final home. My parents sold their house in 1996 and moved to a “safer” part of Bessemer where, among other seeming virtues, there were no alleys and the neighbors rolled their garbage cans to the street in front of their houses every Tuesday and Friday. The cans themselves were large green city-dispensed rolling bins, big enough, one would assume, to prevent the angst my parents felt at the old house after holidays when the garbage collection was postponed, and the collected household refuse overflowed.

It didn’t though. Apparently, there was no bin large enough to collect all of our garbage neatly and tidily. Even when Dad burned the wrapping paper and boxes from our holiday gifts, defying community standards, the cans always overflowed. And he refused to buy or ask for more. It was as if his ritual had to go on; as if he didn’t really want to contain the garbage at all, because doing so would diminish the holiday spirit.

I look at the photo now, as if I were peering again from that back window. I see a little boy standing by himself in his back yard, a place he knew and often feared, wondering whether his daddy would come home on time so they could eat supper and maybe play some games afterward. There were never any guarantees, even though his daddy did come home every night, parked that Chevy, or Pontiac, and later an Oldsmobile and Buick, into that tight garage without incident.

And given his rigidity and OCD, it’s still a wonder to me that after I turned sixteen, he asked me to park his car in the garage each night. No matter what we think of people, they often defy our contained notions.

I still took the garbage out each night, too, often unwillingly, but then, what else do we expect from a teenaged boy?

Today, I take our garbage to the green rolling can at the side of our house whenever it needs to be done, though I don’t do so every night. Three and even five days can go by before I make my way, usually in daylight but sometimes at night, to that can. We have a motion-sensitive floodlight that affords me whatever sight-path I need. I see spiders on my path, and on occasion, a raccoon, but nothing else menacing. Each time I go, however, I think of the scared little boy I used to be. It’s just my wife and I now, our daughters grown and living on their own, so our can never overflows. When a holiday comes—like Labor Day today—the city collects on the following day, so no worries.

Behind our house, at the back of the lot, is a creek that lies almost fallow. But when the rains come, in the worst of times, it gets to overflowing. We have a dog that barks at any stranger who passes out front or through the woods in back. There is no alley, and when I move the rolling can for pickup, I roll it up our driveway to the street. I walk our dog out front, too, day and night, and when he circles to relieve himself, I scoop his droppings in a sanitized bag and toss them in one of those green bins—ours, or a neighbor’s, but only when that coast is clear.

We are surely better off with lighted and clear and large enough garbage paths, though I wonder if putting your mess out front is just another sign of our collective lack of decorum; our ease and comfort with displaying our junk, who we are and who we’ve been.

It’s so odd, but I think about the old garbage days when I’d hear my mother call, “Buddy, take this garbage out now!” She’d hand me the plastic pail or the grocery sack full of all we had and partly were, and I’d begin my journey, mainly believing but never fully knowing, that all would fit.

That I would find my way back home again.

And now I wonder: is that gesture I’m making in the photo from 1959 an attempt to relieve my mother of her burden? Of a sack she’s carrying down the uneven hill? A pail that’s too heavy for her? A job that in this early moment of my life I’d have been only too glad to assume?

I never knew how or why my parents determined that my main house chore would be to carry out the garbage. When I left for college, my brother inherited that duty, and after, my Dad took it over again until he got too feeble to do. When he passed, that job, like all the others around the house, fell to my mother who, every Monday and Thursday night, escorted her can down the driveway to the street, and in the mornings, back up again. She did so until the last week of her life—this past July.

With that long view, the one from Hazel Motes’s second floor door in Taulkinham, Georgia, or my screened-in deck in Greenville, South Carolina, I saw her on all of those garbage days, assuming that she would complete that chore safely, that nothing would stop her. That is, until it did.

Share this post with your friends.