Virginia landscape artist Frederick Nichols remembers photographing the moon from a Brooklyn rooftop years ago, surprised with the photos’ good quality. It was 1970 and Nichols was a graduate MFA student at the Pratt Institute. The year before he’d graduated from UVA, majoring in studio art under the tutelage of realist painter Robert Barbee, an academic traditionalist wary of photography. “I didn’t want to be a photographer,” says Nichols, “but I began experimenting with photography as a way to capture something to work with in my paintings.”

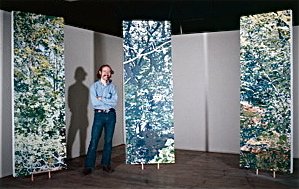

For starters, Nichols decided for his thesis to create panels showing 360 degrees of a summer pond near his home in Charlottesville. “I set up my tripod on the dam and rotated it for a series of vertical images equal distances apart,” he says. Nichols then projected the photo slides onto canvas that resulted in nine panels, each 30” x 9’ or 108,” a diorama that would take him two years to paint.

“While painting, I was in another world. It was my escape from the city, a way to go back to Virginia,” he recalls. Nichols’s ambitious project set the young artist on his course to acclaim for his large-scale, minutely detailed works of woods, streams and wilderness.

At 65, Nichols’s works are featured in Nature Revealed at The Peninsula Fine Arts Center, Newport News, mid-October to mid-January 2014. His “mini retrospective”—Forty years in the Blue Ridge—includes some 40 prints and paintings as well as photographs shown for the first time.

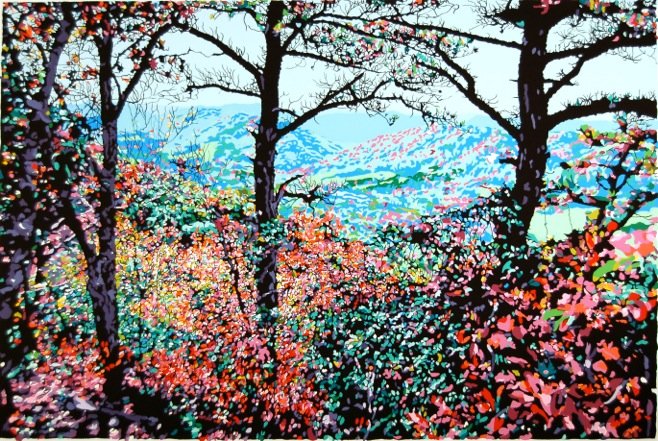

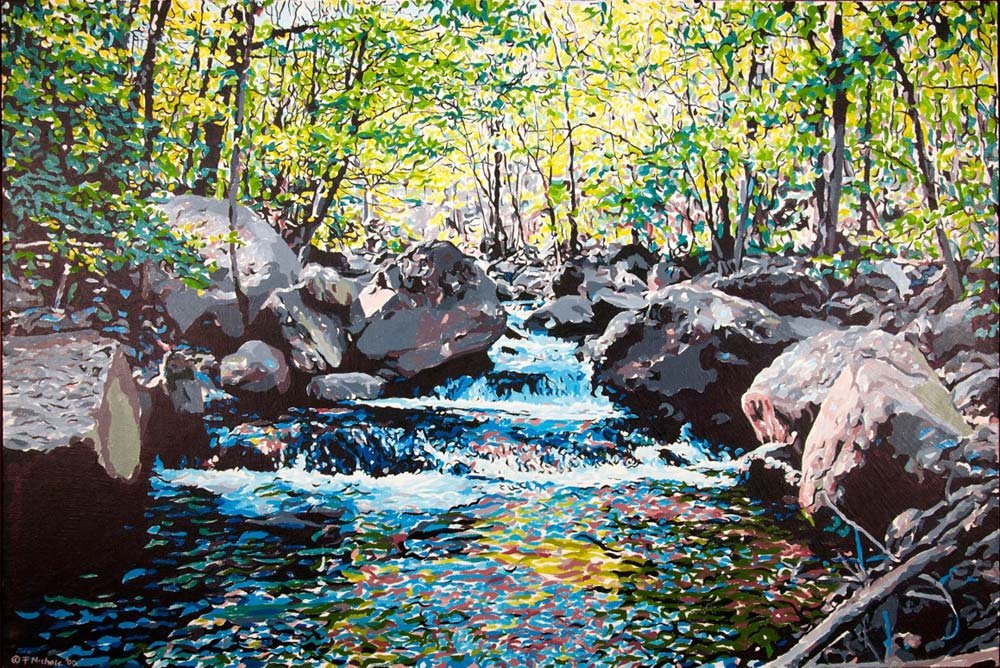

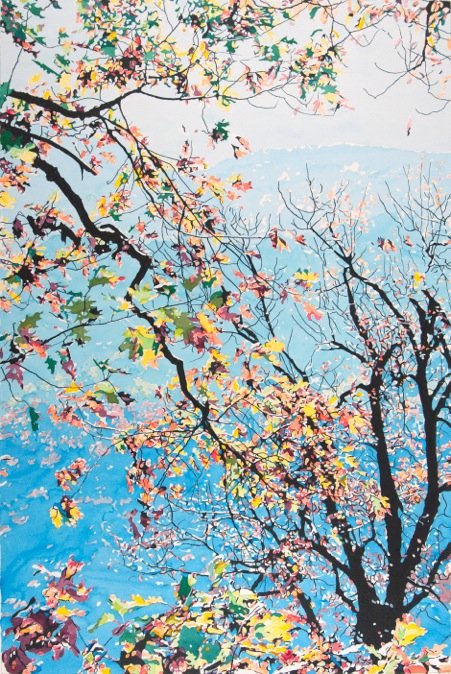

Nichols’s translucent landscapes, paintings, and silkscreen prints depict his native Virginia countryside: pre-historic mountains, hidden streams, woodlands and meadows season to season. “The objective of my art is to recreate the natural world that surrounds and forms us. We are increasingly separate from nature, living more and more in a man-made and designed environment. Through my study of the wilderness, I hope to renew an interest and desire not only to protect, but also appreciate, the natural world,” says Nichols, also a graduate of Ecoles Des Beaux Arts, Fontainebleau, France. He’s also quick to acknowledge the influence of Hudson River painters Thomas Moran, Frederick Church and Albert Bierstadt, as well as Impressionist Claude Monet, post-impressionist Vincent Van Gogh and abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock canvases that reveal “the complexity of nature.”

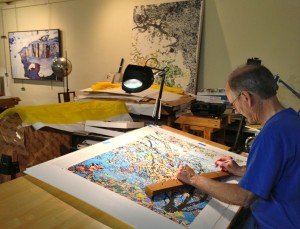

Creating his impressive, oversized yet intimate works is an intense, laborious process. “My method,” Nichols explains, “is to go into the wilderness and photograph, returning to the studio to paint. Working with the photograph allows me to capture a place, one moment in time, one season at a time. The photograph is the starting point of a search for a new reality. I take apart the photograph and reassemble it in a painterly manner, and a new landscape evolves. I project slides on the canvas, and paint as though I am looking through a window. This window allows me to constantly view and experience what I am painting. It also serves as a reminder of the atmosphere that I have witnessed, its sounds and its smells.”

Nichols began using photography as part of his creative process as early as his first Brownie box camera. He traded up for a Minolta while he was deciding his Master’s thesis. Over time, wanting more control and quality images, he developed slides in his own darkroom. “When I’m walking through the hollows and gorges in the Blue Ridge finding subjects that interest me, the light is moving quickly and constantly changing the scene. Photography helps stabilize and capture the moment.”

Although photography and optical aids—from the camera lucida to camera obscura—have aided artists for centuries, including Vermeer and the Impressionists, Nichols’s imaginative employ of photography was once considered controversial. He remembers visitors to his studio in the ‘70s remarking that using photography in the painting process was, in fact, “cheating.” For years after that, Nichols closed his studio door while working. No longer. “The idea (of ‘cheating’) started with the Photo Realists – Richard Estes, Chuck Close and others who made their paintings as close to photographs as possible,” says Nichols. “Some thought it not serious art. Ironically, their work actually gave me the confidence to go against the grain, using photography in painting landscapes. Digital photography can capture what I’m looking at in high resolution. It offers artists another effective tool.”

“I’m intrigued with Nichols’s use of the photography,” says Michael Preble, PFAC curator and a photographer himself. “The ability to use a camera to capture a moment, and then make the transcendental leap to painting and prints, while capturing not only that moment but also a sense of timelessness, with both realistic and abstract elements is really quite an achievement.”

“Early in my career I was exposed to relief printing, particularly woodcuts,” says Nichols, also an admirer of early Chinese and Japanese landscapists. “Although now I do more silk screens, the two mediums have much in common. Silk screens allow a painterly approach to printing, along with a rich color unobtainable in any other process. My approach to printmaking has not been to reproduce a painting, but to recreate the image in a new medium. Printmaking has always been a special to me. I am fascinated by the qualities and the possibilities inherent in the various printmaking processes, and the ability to make multiples of an image.”

“The challenge is to present these experiences in a way that engages the viewer. I want my art to be positive and uplifting. I want it to wake people up to the natural world around them. I want it to give them a respite from the stresses of everyday life.” Over the past four decades, Nichols’s highly regarded work has been exhibited across the U.S. and internationally—from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts to the Rich Perlow Gallery, New York, the Juried Membership Exhibition, Los Angeles Printmaking Society, and Italy’s invitational Florence International Biennale to Japan’s international exhibition, Renascence, at the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, Kobe, commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Post earthquake restoration in Kobe. Nichols’s works have also hung in several U.S. embassies including Panama, Madagascar and Uzbekistan. Nichols and his wife, Beth, own the Nichols Gallery Annex in Barboursville, VA. In 2003 The Piedmont Council of The Arts awarded the Nichols their lifetime achievement award for their contributions to the arts in the region.

For further viewing of Frederick Nichols’s work: www.frednichols.com

— Elizabeth Meade Howard, Art Editor

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.