Machinery and tools—their design, operation and production—were early interests that would shape Blake Hurt’s professional and creative life. “I picked a field of engineering that would be relatively durable over time, where the current knowledge was unlikely to change. Computers change with the year, gears are forever,” says Hurt, a Virginia artist who earned degrees in mechanical engineering and business management from The Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Hurt worked briefly in New York finance before returning home to Charlottesville to establish his own building company. “When I started working in the building business, I drew many of the plans myself. It’s a pleasant thing to do, drawings of what you think something is going to look like,” he says. “After a while, I found more interest in doing the plans than other possibilities because the buildings themselves often times were restricted by various factors. I had ability to draw but it was not art. I didn’t really connect to the idea of the drawings being ends in themselves. I later realized you don’t have to make the drawings into something. Just call the drawings art and you’re done with it.”

Beyond the drawing board, Hurt’s first efforts were abstract, inspired by Jackson Pollack and other Abstract Expressionist “drip painters.” “I bought some paint, and literally threw it onto the canvas. I thought ‘that’s interesting but there’s not much language, elements that convey a more complex emotional message. You can’t express but so many feelings or ideas.” Hurt’s early abstracts show his long attraction to geometrical design, among them black and white drawings of a locomotive spread out like an animal skin, “a locomotive hide,” and a motorcycle composed of animals including a wriggling python as the muffler.

“At some point,” says Hurt, “I realized that if you’re going to make art, you’re going to have to master colors.” In 1995, he ventured into realistic painting, studying for some years with UVa landscape artist Richard Crozier. “We sat side by side painting the same thing—the first 10 percent of the picture—and then he put on that next stroke and I realized we were diverging. Pretty soon the picture he painted looked nothing like what I had done. His looked very much like it and mine had some serious problems.”

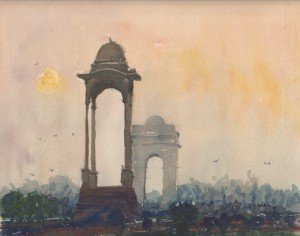

Working in oil and watercolor, Hurt continued to paint en plein air scenes in Virginia as well as many on his world travels. Whether ever-greens along the Rhone, spires in India or gateways in Greece, his choice of subjects again evidenced geometric appeal— lines and angles, curves and shadows in planes that divided and enlivened the surface. In December, Hurt will exhibit recent watercolors of Vicenza at The New Dominion Bookshop.

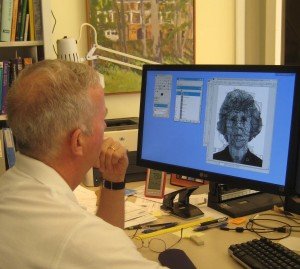

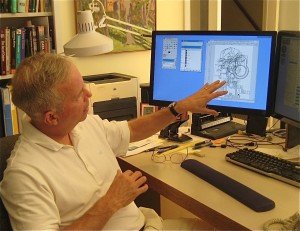

While painting realistic scenes near and far, in the late 90s, Hurt also began exploring ways to draw on the computer. When he found software limited, he created his own. “The computer has an infinite amount of patience for detail. You need to think about how you’re going to end up with an overall idea, but it takes care of putting masses of the detail to give you the texture you want.”

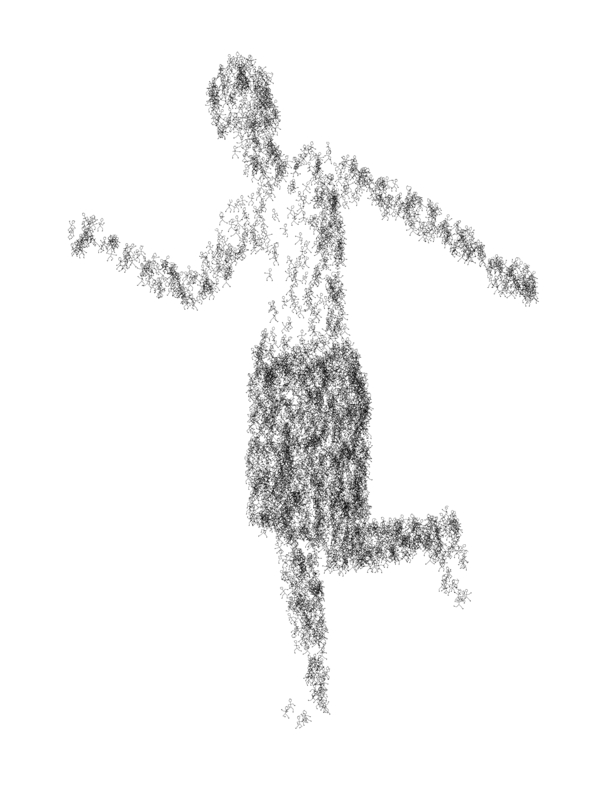

Hurt, always intrigued by the human face and its many revealing expressions, wanted to create thought provoking portraits of family and friends. He began with photographs, replacing the exact picture with thousands of dark and light repeated images related to his subject. Morse code messages expressed a friend’s hobby; a circle of prime numbers morphed into a mathematician’s face; a series of hexagons and diamonds transformed to Hurt’s son, Ben; 1001 mini dancing stick figures assembled into a larger-than-life likeness of his wife, Carol.

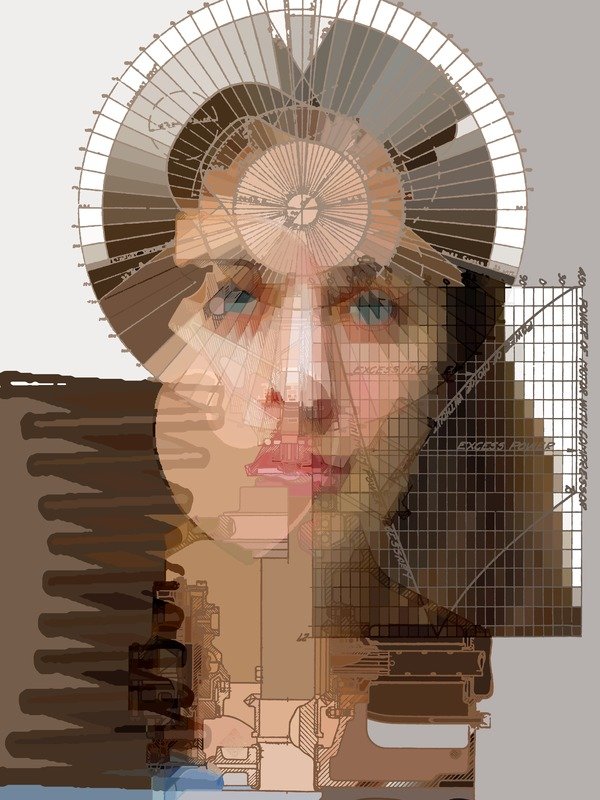

Hurt initially “drew” his highly original portraits in black and white. He later rewrote the software to add color. Soon his restless imagination led Hurt to even more complex and intensely personal portraits that included more biography. Again using frontal photographs, he superimposed a visual of personal importance over the photo to create a fluid, layered and arresting image. Calling his unusual technique, “ink collage,” he layers a series of drawing to form a mosaic of openings through which he digitally “squeezes” color. An Indian-born city planner merges with designs of his adopted community; Moorish tiles form the intricate features of an African American friend; a psychiatrist emerges from a three dimensional maze and jigsaw puzzle; a chess master studies his next move, embedded in the game; a child peeks through a cross hatch of favorite words, forks and spoons, dolls and butterflies.

While Hurt says he was not directly influenced by painter/photographer Chuck Close, he acknowledges their similar manipulation of Photo Realism to create complicated portraits. “I also break the images apart. I didn’t realize that essentially we’re doing some of the same things. He’s very careful about his painting. I’m more interested in how much ‘information’ you can put in the picture, not just the difference in the image.

“I did think about the medieval painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo who makes faces out of fruits. I think of being a visual heir— combining disparate images that make up something else. I also like Klee.” Paul Klee’s experimentalism and fanciful influence seem to surface in Hurt’s 2013 watercolors, a nod to America’s early 20th century industrial explosion with whimsical animals and humans part of the mechanical innovations.

Having worked in digital formats for more than 15 years, Hurt continues creating portraits, his latest underscoring a continuing affection for all things mechanical. His new “Steampunk” series employ photographs combined with machine parts of the 19th century, “the golden era of mechanical devices… with steam power affecting every aspect of life from apple corers to zeppelins. “The drawings are in these dusty books of engineering. When I choose an apple corer drawing to put in a work, it can be considered a style of drawing or simple aesthetic device— it looks long and skinny. It can also be considered a sly reference to Adam and Eve.

“In using these drawings of 19th century draftsmen, you’re basically reviving their work. These works are less personal in the sense that the underlying objects are not necessarily anything about that particular person, but are elements used to describe them in a different sort of way,” says Hurt. “Now they’re essentially revived and pieced together into a human form. The portraits are a reminder of the physical logic of an earlier, simpler age, and touch on a counter-factual image of a modern world powered by steam. I’m not saying I’m a modern day Dr. Frankenstein but it’s kind of the idea of reviving these drawings in a way that makes them current with people alive today.”

Hurt’s Steampunk show will be on view at Eppie’s in Charlottesville until January 30, 2015.

As Blake Hurt continues to experiment with art inspired by engineering, his varied work has been exhibited in more than 50 shows across the country. He has won numerous awards and conducted computer presentations of his original techniques in Kyoto, Japan and Copenhagen, Denmark.

Visit blakehurt.com to see more of Hurt’s paintings and digital portraits.

–Elizabeth Meade Howard, Art Editor

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.

I really love the way he uses a street map to create a mosaic.

Wholly agree with Spriggan.

add me to subscription list