In His Own Right

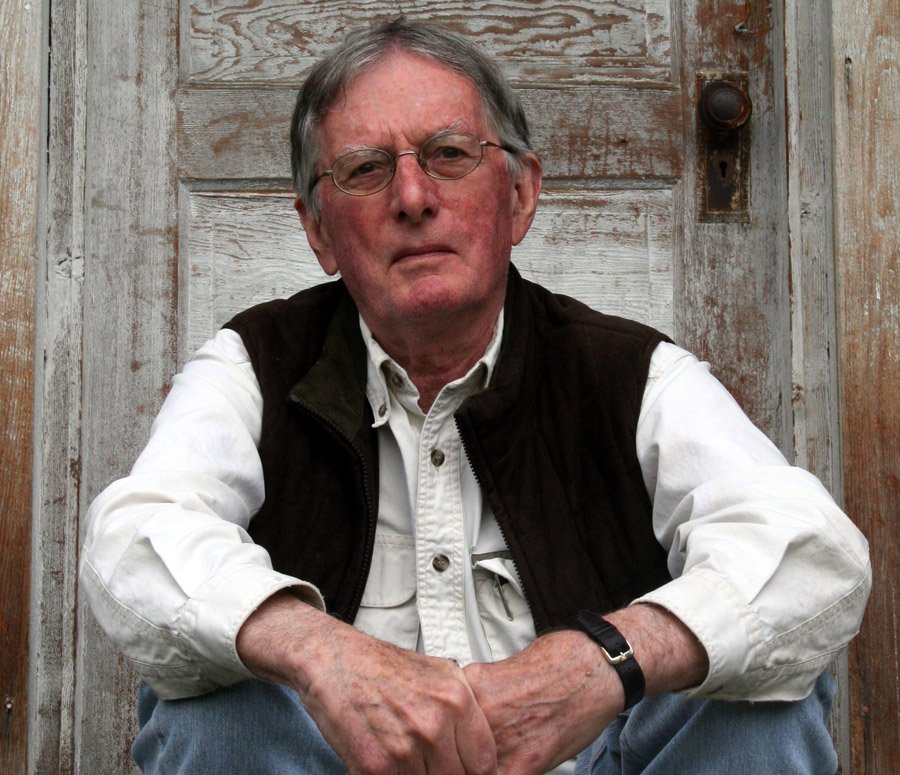

A conversation with U.S. Poet Laureate and Charlottesville resident Charles Wright

What the city of Charlottesville, Virginia lacks in size it makes up for in culture. You won’t go ten minutes without passing a building bearing a whimsical mural, a metal sculpture gracing the bypass, or banners advertising book and film festivals and Live Arts performances.

What the city of Charlottesville, Virginia lacks in size it makes up for in culture. You won’t go ten minutes without passing a building bearing a whimsical mural, a metal sculpture gracing the bypass, or banners advertising book and film festivals and Live Arts performances.

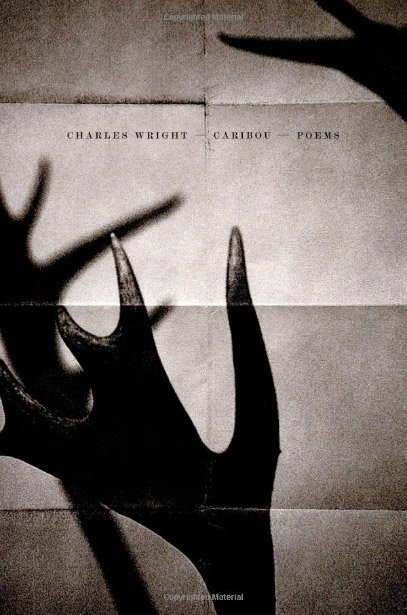

So we’re particularly proud to call poet Charles Wright one of our own, and not just because he’s the current U.S. Poet Laureate. Wright served as a professor of English at the University of Virginia for over 30 years, and his poems are masterful responses to the ineffable mystery of landscapes both local and afar. Throughout his career, Wright has published over 24 books of poetry and is the winner of the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the National Book Award, the Griffin Poetry Prize, and the Bollingen Prize for American Poetry.

Amidst numerous public appearances and interviews for his new role, Wright sat down with Streetlight for an interview, and we’re grateful.

There’s a lot of talk these days about how different childhood was 50 years ago. How would you describe yours and your family life?

CW: I remember my childhood as being very happy. We lived in places that were interesting to me, although I’m not sure they were very interesting to my mother. My father always said, “There’s no city or town I’d rather live in than outside of.” So we were always outside of town, which was great for me, I liked that. But my poor mother spent her life behind the wheel taking us in to town and back.

There were never any fights in my family. I never rebelled against anything the way all my friends seemed to have done. I just sort of went along with whatever my parents were doing, since I didn’t have any reason not to. Their parents were raised Victorian, so I guess my parents were raised Victorian, though they weren’t that way with us, but you knew what kind of background they were coming from. Always said, “yes sir” “yes ma’am” to my parents—which is not the case in my house.

Your Mother has floated in and out of your poetry and was an aspiring writer?

CW: That’s what I’m guessing. She never told me that, but after she died—very young, age 53—I found parts of stories she’d tried to write. I’ve told this story many times, I’m sure you’ve heard it, but at the University of Mississippi she dated William Faulkner’s brother, the one who got killed in an airplane crash. So she always had this feeling that it was a good thing to be a writer.

What kind of exposure did you have to literature in your school years?

CW: In high school there was never any encouragement toward literature, though I read all of Faulkner before I graduated, which was really stupid because I didn’t understand it but figured I was done with it. There wasn’t much more encouragement in college at Davidson because back then there was only pre-law, pre-ministerial, pre-business. Now all the courses I would’ve wanted to take are now being offered. There was one writing course offered every other year by the Shakespeare professor, so I didn’t really get interested in that. I was sort of co-editor of the literary magazine, such as it was. But I was never the guy who’s always writing poems or anything. It was all purple prose, since lyric seems to be my avenue.

We’ve heard would-be poet/English professor was a history major at Davidson?

CW: I just fell into being a history major because, at the time, I was interested in Southern history and took so many history classes that I ended up having enough to be a major. I could’ve been a double major in English, had I declared it, because I took enough English courses. Of course that’s where my interest was after my second year, I guess, after I’d already compiled all the courses to be a history major.

Have you had any heroes or role models along the way?

CW: Well, back in highschool, I liked Sam Snead and Ben Hogan—I was a golf nut. And I never really wanted to be like my father because he did stuff I wasn’t interested in, like construction. He understood that I wasn’t interested, and he never pushed me to get into that business.

Once I grew up I had two very strong heroes: Peter Matthiessen, I liked the way he lived his life and W.S. Merwin was the other because I liked the way he lived his life, too. And I liked both their writings. There are always people who you admire, like my teacher, Donald Justice—I admired his writing tremendously; my friend, Mark Strand, who just died, he was a year older than I, and we were in school together and I admired him and what he was doing very much.

I didn’t have any real literary heroes…I guess you could say Faulkner was a writer I’d at least heard of; and once I’d read Hemingway, he was a real force, until I learned what an asshole he really was. Still a great writer, though.

Speaking of influence, your wife, Holly, is a photographer and retired from teaching at U.Va. in 2000 after 16 years. What kind of creative input do you give each other in your work?

CW: She’s the only one who reads my stuff before it goes to the publisher, and her opinion matters me a lot. As I said, she’s very smart, very literary, she’s read more than I have. Of course you could drive tanks through the holes in my literary background. After a while, I never sent anybody any of my writing, figured I was doing what I was doing, and nobody else is doing it, so what do they know? It would’ve meant a lot if I’d brought myself to do it.

Holly shows me her work. I love her photographs and how serious she was and is about it. I used a couple of her pictures on a few book covers (Bloodlines, Chickamauga, Scar Tissue). She was a great teacher; boy, her students loved her. But there was never any reciprocity between our two disciplines.

You’ve lived and written most of your poetry here in Charlottesville for the past 30 years; do you consider it home, in the grander sense?

CW: I consider it where I live, I don’t know if I consider it home. I always think of Kingsport as being my home, where I grew up. Holly certainly doesn’t think of it as home. Our son Luke seems to like it, which was one of the reasons we came here, because he was getting to be 13 in Southern California and we didn’t think that was a great thing. But yeah, it’s where I live, that’s about it. I don’t want to be in Kingsport, don’t get me wrong, but that’s sort of what I think of as home, east Tennessee.

You’ve mentioned many times how your own back yard is a source of poetic inspiration. Do you favor any other spots for a landscape high?

CW: Not really. This is the prettiest county in Virginia, once you get up past Garth Road. It’s just beautiful out here with the Blue Ridge mountains.

Interview by: Lisa Ryan

Follow us!

Share this post with your friends.