My father was an aviator in the Great War.

He was also 40 years older than I, and understandably we did not share a lot of the things little boys and daddies are supposed to share: like tossing around a football or baseball or his telling me stories of his youth and how he became who he was. And, he was a hard-driving, self-made man, from the slums of South Bend Indiana and yet gained entrance into the Notre Dame School of Architecture, from which he left to join the American army sometime in 1917.

I never knew him well enough to know if he was prone to self-reflection, even though we spent a lot of hours together walking in the woods and I answering his office phone. (He hated the telephone).

So it was, we were well into the Second World War before I discovered much of his personal history. I was six or seven, when one afternoon, my father dug into a trunk with his name and a lot of numbers on it. In the trunk, which I later learned was called a footlocker, was a gas mask, a helmet and a uniform, all of an older vintage than what I was becoming used to seeing in movie newsreels. When I asked him what they were, he just said, “they were mine a long time ago.”

I turned to my mother. She did not have a great deal to add as my father’s war experience was before she had even met him. She’d been a teenager in the Great War, but she had uncles and cousins who had participated. One had died in a flying accident when his plane lost power just after he had taken flight.

My mother told me only that my father had been in France, he had helped bury lots and lots of young American soldiers who died of flu, and that she was fairly certain he was the last man in his squadron to survive the War. I didn’t know how many men were in a squadron back then.

One spring afternoon a few years later, my father told me more. We were in the living room, the sun from the French doors on the yellow carpet as we listened to the war news on the radio. The announcer talked about the wonders of the British Spitfire. My father said “they were so much better equipped than we had been.” He had sat in the rear seat as an observation pilot. Between him and the man in front, were only a few feet of plywood and dope-soaked canvas that covered the gas tank of the airplane. “That canvas was all that stood between the two aviators and the German bullets,” he said.

Speechless, I later discovered from reading that the job of the observation pilot was to locate the enemy’s artillery, masses of troops, or other important targets, and telephone back those locations to his own artillery. I came to realize that my father was in fact the crucial link in the process. He found the targets, he told the guns where to hit them, and shortly after he sent his message a hell of bursting steel and explosives would fall on young German men, killing or mutilating them. He died before I ever asked him how he felt about his part in the war, including the flu victims.

I used to have a photo of my father as an aviator. Although it’s long lost, I remember a sternly handsome young man, even in the yellowed picture his blue eyes direct and clear, his chin sculpted as though he were a movie actor.

We talked about the War only once again. I was teenager and we were walking in the woods. It must have been October in Virginia, for the leaves were falling, and the sun had that wonderful soft sadness it gets that time of year in that place. We stopped, and he pointed to a red and yellow leaf slipping and falling to the ground. He said, “That is exactly the way an airplane falls when it is shot down.”

We watched the leaf come to rest on the ground and walked on. I still think about what he remembered.

— Stan Makielski is a retired professor of political science who now lives in Tallahassee FL. When he is not walking his schnauzers, he reads about World War I and dreams, occasionally, of writing.

VIRGINIA DOCUMENTARY TO RE-AIR THIS WEEK

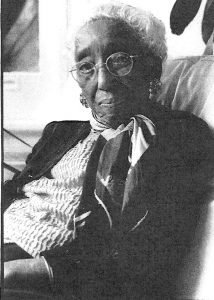

In the Fullness of Time –– a film written and directed by Streetlight art editor Elizabeth Howard –– will re-air at 9 p.m., Thursday, February 18 on Virginia PBS stations, WCVE and WHTJ. The half hour documentary tells the story of Rebecca McGinness, a revered 107 year old teacher who taught for more than 50 years at Charlottesville’s Jefferson School. The film is narrated by poet Rita Dove.

Follow us!

Share this post with your friends.