She was a bully, a backer, a stinker, a treasure. She was a finder of fault and forte, folly and facility. She was the picture of rigor and push and impeccability, her visage stern and stately and a dead-ringer for the man on the one-dollar bill. The first time I saw her standing on stage in her blue satin suit and snow-white hair delivering a rule-laced welcome to school, I felt wings of butterflies and tips of prayers brushing my soul in a nervous wish for her retirement to sync with my grade six arrival. She had a knack for touching nerve and enterprise and was, herself, a touch of task and class and calamity. She was the scent of lemon and chalk and Duz Detergent. Even with heads lowered to our desks for sundry infractions, we knew by the tart waft of petulance exactly where she was in the room. She was an acquired taste and a hard-to-swallow medicine and a hater of sentence-stuffed clichés who’d rightfully spit this one out.

She was my sixth-grade teacher, Miss Madden.

Her hair was whiter than ever the year we filed into her class just after Labor Day 1962, at Abraham Lincoln Elementary School in East Braintree, Massachusetts. My desk-mate of many years, Will, made a wisecrack about her uncanny resemblance to George Washington and she promptly escorted him to a desk in the middle row, sans the familiar ear lobe squeeze, the preferred maneuver of earlier-grade martinets. Perhaps now, things would be different, I thought, this being our senior year of sorts as she solemnly reviewed the no-talking statute along with a few other canons of acceptable behavior with which many would struggle through 1963. I noticed the mostly boy-girl, double-desk pattern in her stacked-deck, seating chart strategy and, for the first time in my academic life, I was partnered with a girl, Roxanne, the teacher’s pet and Lincoln School’s tattletale-in-chief.

It wasn’t so bad sitting next to Roxanne who knew all the answers to everything. She was the patron saint of punctuation and, for some reason, took me under her wing when it came to apostrophe and comma application. I think she looked upon me as practice time for her own teaching aspirations, a kind of personal pedagogical project. She was, however, a notorious busybody and fink and seemed to derive much pleasure in turning me in whenever I stole time to read Hardy Boys books under my lift-up desktop. She was righteous and buttery and ruinous all at once and she smelled like my grandmother’s geranium, kind of lemony like Miss Madden.

Reading was becoming a problem. Not that I had trouble reading but that I was reading too much. Before reluctantly promoting me to grade six, Mrs. Smith, my fifth-grade teacher, wrote in the notes section of my report card, “Richard wants to spend all his time reading—consequently his other work is suffering.” The “other work” was most notably Science in which I received the unwelcome grade of N, and listed in the Explanation of Marks box of my report card as Needs Improvement. Somehow, the study of things like fungi and states of matter and photosynthesis could not compete with the adventures of detectives Frank and Joe Hardy. I remember how I’d pretend to follow along with the class during the read-aloud about evaporation and condensation, when, in reality, I was devouring another chapter in The Secret of the Old Mill (Dixon, 1962). As Mrs. Smith patrolled the aisles, I’d stealthily slide the outlawed book under the text and, for the longest time, the ruse worked without a hitch. But…Lincoln School was rife with tattlers and turncoats and, before long, one of the whistleblowers, with a hunch and a high-minded way, sounded off.

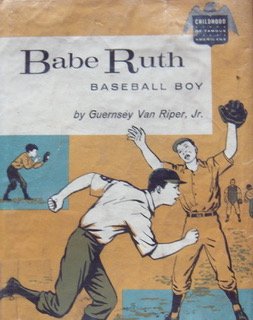

Miss Madden didn’t waste any time in addressing Mrs. Smith’s concerns, specifically the madcap Hardy Boys reading craze. And, it probably didn’t help that she was listening to Roxanne’s gleeful bean-spilling play-by-play. So within the first few weeks of school, she pulled me aside one morning just before recess and asked me about my other reading interests. When I told her I followed the Boston Red Sox in the sports page of the Quincy Patriot Ledger, she led me to a bookshelf in the corner of the room and handed me a book, back-side up, with the image of a familiar figure swinging a bat. When I turned it over, I saw an illustration of a boy running the bases. It was Babe Ruth…and a rush of holy smokes spirituality and the beginning of a whole new ballgame. That one book, Guernsey Van Riper’s Babe Ruth-Baseball Boy (Van Riper, 1954), which was part of the Childhood of Famous Americans (CFA) series, changed everything. Before long, I was reading other books in the series like Wilbur and Orville Wright: Boys with Wings (Stevenson, 1951), George Eastman: Young Photographer (Henry, 1959), and John Quincy Adams: Boy Patriot (Weil, 1945). I tended to select books based on their covers like the Wright brothers running with the giant kite or the mysterious, draped curtain over the man’s head taking a picture with the old-fashioned camera on the front of the Eastman book. I balked at Miss Madden’s suggestion a few weeks later about reading Noah Webster: Boy of Words (Higgins, 1961) because a small boy in a rocking chair with a feathered pen just wasn’t my thing. And, as for her recommendation of Paul Revere: Boy of Old Boston (Stevenson, 1946) with the pencil scribbles all over the place, why would I ever read something so old and orange and without a cover picture? That’s when I got the look and a lecture about not judging a book by its cover.

The look was never a good thing. I first saw it the time we had a paste fight in second grade while Miss G was called away to the office to take an important telephone call. Before leaving the classroom, she instructed us to continue cutting and pasting circles, squares, and stars from the stacks of colored sheets onto our cream white poster boards. Within two minutes of her departure, Leonard, who sat behind Sandra, tried pasting her unusually long braid of chestnut brown hair onto his poster next to a pitifully cut star that looked more like a saw-toothed muffin top. Sandra, who didn’t care for the idea, then scooped up her glob of paste and smeared Leonard’s face with most of the concoction, streaking both eyebrows and part of a nostril. Things worsened when Eddie started finger-flicking portions of the sticky gunk in all directions and, before long, there was a full-blown coup de glue. When Miss Madden walked in, Fitzy and Gordo were coating Tommy with arithmetic paper upon which the dollops of ammo initially sat. She quietly moved to the center of the room and the clock stopped ticking and the clouds covered the sun and we stood there in sweating-bullets-silence and watched her lips tighten into straight lines and listened to her eyes say things like we had never heard before.

Fortunately, the look she gave me was a much more watered-down version of the one we witnessed four years earlier. But it was effective enough to get her point across and I promised to add the Revere and Webster books to my reading list. And so it went for the rest of 1962 and into 1963. With a new-found sweet tooth, I polished off every CFA book in our classroom collection and, with urgent appetence, burned a trail to the Thayer Public Library branch near Weymouth Landing every day after school to wolf down more. I was beginning to see science in a different light and found myself becoming a fan of John Audubon: Boy Naturalist (Mason, 1962) and Maria Mitchell: Girl Astronomer (Melin, 1954). As it turned out, Miss Madden was right. The books without picture covers or ones with simple illustrations like the light bulb on the front of Tom Edison: Boy Inventor (Guthridge, 1959) were as good as the ones with the best sketches like the boy talking to the man with the Mohawk hair by the teepee on the jacket of Tom Jefferson: Boy of Colonial Days (Monsell, 1962).

When it came to securing a slot on Miss Madden’s special jobs list, one had to be part of the academic upper-crust circle, the A-Excellent crowd. These were the children who had developed a kind of yellow gleam to their foreheads, a delicately weathered sheen from years of gold star wear. Roxanne, for example, had the glow. So, too, did Elizabeth and Martha. As a result, they were rewarded with the more privileged duties of answering Miss Madden’s telephone if it rang during class or running the mimeograph machine for grammar tests or delivering important messages to the traveling dental hygienist who sometimes visited to give us fluoride treatments. The less desirable chores like washing blackboards, taking out trash, or clapping chalkboard erasers were relegated to those of us in the lower rungs of the scholastic ladder. Of course, some reveled in such labors, ignoble as they were, masking their nefarious intentions with mock industriousness, patiently awaiting the inevitable breach of surveillance which always came when Miss Madden was needed elsewhere. These were the moments Larry, the blackboard washer, lived for, his spongy handiwork the bane of those unlucky enough to be doing after-school detention stints, their apparel and footwear immediate targets of his errant rinsing schemes. Same thing with Arnie, the chalkboard eraser wall-banger, who infuriated Miss Soley, the kindergarten teacher, by leaving long white streaks on her classroom windows. Both were loose cannons, bad eggs who were dishonorably stripped of their short-term posts and sentenced to serious corner time.

Amid their buffoonery and eventual fall from favor, I continued to read about famous young Americans like Zeb Pike and Jim Bowie and even one about a Girl Scout by the name of Juliette Low. I discovered that I was not alone in my growing addiction as Jake and Bugs and Joker were under the influence, too. We became word-droppers based on what we were learning and quizzed each other on the meanings of words we were picking up from the vocabulary exercises in the back of each book. And before I knew it, I had a new job and erasers to clap. I also had a few misgivings: the Rust Brothers Gang, junior high school bullies who were known to chase down former clappers to steal erasers. As they rode away on their bikes, they’d shout, “You ever tell Old Lady Madden, we’ll getcha.” Getcha could mean many things like get you while you were walking the path alongside the school’s neighboring woods and force you to smoke a cigarette like they did to my brother or get you while you were walking under a tree after a rainstorm and shake the living daylights out of a branch to drench you. Yet, onto the playground I went after school with vigilance and focus and an armful of erasers with the sole purpose of scattering into powder the day’s work of fractions and verbs and eighth notes and fine loops of penmanship. But there were flaws to my cymbal-like theatrics and I knew it because of all the dust in my mouth and up my nose and in my eyes and so did Miss Madden who, one day, told me to lift my hands way up high like I was applauding the sky and, with an eraser in each hand, she began resolutely waving to the heavens, kind of like someone with a flat tire alongside the highway trying to flag down cars for help. And from that surrealistic day on, thanks to Miss Madden, I rallied clouds and helped whiten the wild blue yonder.

Nicole Resseguie-Snyder. CC license.

Words were the world to Miss Madden and she believed that if we could make them our own, we wouldn’t have to dig ditches or work in the ship yard or drive a horse-pulled wagon like Mr. Haines who collected old newspapers and whose “bags and rags” bellows up and down Hobart Street scared the crap out of us. So each week, she would hand out perfumed-inked sheets of look-up words freshly rolled from the mimeograph machine, usually by Ava, one of the A-Excellents. Below each word was a space for sentence-usage to demonstrate our smarts and grasp and deep-seated acumen. This is where it paid to be on the word-droppers team because Jake and Bugs and Joker and I had been collecting words like Red Sox baseball cards and making sentences of meaning as easy as Frank Malzone hot-corner snags. But not everyone could field them as effortlessly as we, and kids like Carl and Colleen and Gwendolyn fumbled their way through the exercises, often called upon unexpectedly for their trite sentence renditions which were mostly hollow or lazy or broad. One time, Carl concocted five sentences using words like gloomy, vexed, molting, drowsy, and deciduous prefaced by, “He was…” Flimsy efforts like these angered Miss Madden and she’d make us lower our heads into our arms and onto our desks demanding our undivided attention for the new-ways-of-thinking talk which was something like the sky’s-the-limit pitch that Little League Coach Frickey delivered every year on opening day except hers was more of a sermon. Words were like stars, she’d say, and we should always reach for them. Words led to ideas that often led to questions we’d never thought of that led to more than a few answers that led to new ways of thinking and this was something we should strive for and wouldn’t you know she made strive a look-up word almost every week until everyone had made it their own.

Miss Madden expected the best and not a day went by without her telling us that if you are going to do something, do it right and do it like you mean it. And that applied to everything like book reports and singing on key and coming to school on time with clean clothes and combed hair. You couldn’t just turn in one of your older brother’s book reports hoping she’d not recognize it as Henry found out one dark day in October and ended up standing in the corner all day on Halloween, his feet so swollen that he could barely trick-or-treat that night and those were the days when you could fill three First National Grocery Store bags with Mars Bars and Peter Paul Almond Clusters. When it came to singing, you were expected to toe the line of the pitch pipe and if your notes strayed too far sharp or too far flat, you could expect the dreaded tap on the shoulder half-way through Moon River or White Choral Bells or Git Along Little Doggies which meant it was time for you to stop singing because your off-keyness was sending the group to the whoopee ti yi yo land of no return and no one wanted to be the cause for such a ride. Miss Madden would place her ear close to your mouth to weed out those of the discordant stripe like Jesse who never made it through an entire tune, her convicting thump the kiss of demeaning quiescence and it bothered me because Jesse was my best friend and a stutterer and in desperate need of something that could help untie the knots of strain which just so happened to be the smooth tonic of a song. Miss Madden had a low tolerance for tardiness and the one time I was late for school was the last time I was late for school because of the look that spoke to me in a tongue that nearly sliced my soul and ruffled me so, that I confessed it to the priest behind the purple curtain at St. Thomas More Church the following Saturday who told me I needn’t worry about any extra Hail Mary’s, though I went ahead and said a few just in case. The unpunctuals were the ones to really push Miss Madden’s patience and if there were stars given for after-the-bell belatedness, Priscilla’s temple would have twinkled, especially in the winter because she was last-minute and then some in getting to school. She was one of the poor kids with hand-me-down clothes who lived in a house with broken windows and so little heat in the winter that she’d wake up in the morning with snow on the floor and we all thought it was cool that she could throw snowballs at her brother without even getting out of bed. I can still see Miss Madden’s stiff lips and glowering eyes and angry white hair as the door slowly opened with Priscilla timidly poking her head through the crack to locate her maligner and brace herself for another day of derision.

I was beginning to sense impatience in Miss Madden’s eyes and in her per usual pursed lips and it was becoming more apparent during times of someone’s struggle to sentence a word or channel a note or slip through a door’s narrow crack. Or was it the bold face of focus, a hell-bent determination to will unlikely obedience in learning and harmony and dependability irrespective of screened and lawless puzzles? Was she judging books by their covers? Was there something more she needed to know about Jesse and roadblock letters like m and p and b, and why his mouth and lips and tongue turned on him whenever bully consonants came around? Was there another way to help him land a syllable or two without the interrogation lights that lowered his eyes and esteem and belief in fair shakes? Was there something more she needed to know about Priscilla and cold houses and second-hand clothes and a no-show mom with a reputation? Was there another way to help her beat the clock without the stare that iced her fire and kick and curiosity? I was learning to put myself in the awkward footing of Jesse and Priscilla and the corner-standing kids, and how it must have felt to walk or stand a mile in their shoes. And though I didn’t know the word for what I was feeling and not yet able to use it in a sentence, I was using empathy in practice and trying it out in my head and taking it for a spin the way I did on my rusty, red Schwinn Traveler with the faulty odometer that often fell short of pinpoint reads.

As the winter wound down and the Red Sox set off for spring training to a warm and faraway place in Arizona, I lived in quiet sulk with hear-a-pin-drop ponder that I shared with no one because inside there was guilt and gall and grim bewilderment. I read books and rode my bike and oiled my glove for Little League around the corner. I found quiet spaces in the April-May grasses to study skies for early night stars and contemplated Miss Madden’s talk about new ways of thinking and how that was already happening and how scary it all seemed to be. And on that last day of school in June, I found myself on the playground one more time with erasers to clap and chalk to spread and clouds to call and an odd but unflagging desire to make Miss Madden proud with words and questions and answers I’d one day make my own.

References

Dixon, F. W. (1962). The Secret of the Old Mill. New York: Grosset & Dunlap.

Guthridge, S. (1959). Tom Edison: Boy Inventor. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Henry, J. L. (1959). George Eastman: Young Photographer. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Higgins, H. B. (1961). Noah Webster: Boy of Words. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Mason, M. E. (1962). John Audubon: Boy Naturalist. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Melin, G. H. (1954). Maria Mitchell: Girl Astronomer. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Monsell, H. A. (1962). Tom Jefferson: Boy of Colonial Days. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Stevenson, A. (1946). Paul Revere: Boy of Old Boston. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Stevenson, A. (1951). Wilbur and Orville Wright: Boys with Wings. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Van Riper, G., Jr. (1954). Babe Ruth: Baseball Boy. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Weil, A. (1945). John Quincy Adams: Boy Patriot. Indianapolis, New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.

Share this post with your friends.

Hi Mr. Kenney,

Your article about Miss Madden brought a smile to my face and tears to my eyes. I was a student of hers in 1964-1965. I believe you are the brother of Stephen, who was a classmate of mine from kindergarten on. I lived on May Street, directly across from the school. I think of those days quite often, and drive by frequently – just to keep those memories alive. I remember she would walk up and down each isle and make each one of us stand up, inspect us, and see if we had body odor!! I could go on and on about Mrs. Brassel, Miss Graveles, Mrs.Chiasa, and grouchy Mrs. Smith as well. Lets not forget Mrs. Fink!! A great read – thank you and congratulations on your tremendous success.

My best to you!

Donna McHugh

Hi Donna, I just saw your comments and was thrilled to read them. You lived right down the road from me but I don’t believe I knew you. It’s always great, however, to hear from someone in the neighborhood. Miss Madden was certainly a memorable person and did have a positive impact on my life. I hope you are doing well is these most difficult times. Thank you for writing.

Best regards,

Rich Kenney

Funny I read all of this and I too went to Abraham Lincoln

school back in the 60’s and had all the same teachers.

I did have a strange dream of walking the halls in the school years ago, a calling you could say and went and visited it and allowed inside before it was torn down. I took a piece of red brick the ground after it was torn down and have it as a keep sake. I walked to school daily from # 16 Orchard St off the top

of Hobart St. I am looking for old pics of the school have any ?