Shoes is the story of the artist’s aging father who needed to give up a good pair of shoes because they no longer offered enough support. Harris inked the soles of these shoes and walked in them to make prints on the paper. This book is one of 52 weekly books Harris made in 2013 in a project entitled A Year In Books.

I found book art (or it found me) in 1995 in Florence, Italy, when, instead of painting on paper, I folded it into sculptural forms. I didn’t know the term “book art,” but when I moved to San Francisco in 1998, I discovered there was an organization dedicated to this field: San Francisco Center for the Book. I took classes. Meanwhile, I was also taking evening classes at UC Berkeley in poetry and creative writing. I was still painting and exhibiting paintings nationally. (I’d previously graduated with a BA in Art History from Northwestern, followed by two years of post-graduate art school at the San Francisco Art Institute and the California College of the Arts), but I was increasingly drawn to an art medium where I could bring together text and image. This led to my MFA in Book Art and Creative Writing (poetry) at Mills College.

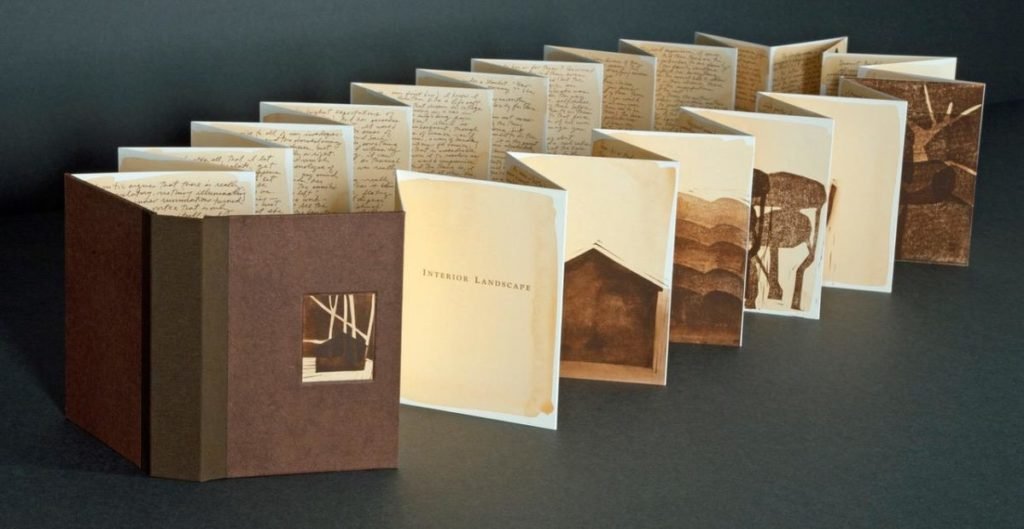

Book art gave me the means to work on subject matter previously untapped in my painting, like everyday themes of motherhood and family history and relationships. Over the past 20-plus years, these themes have persisted in work that also addresses loss and legacy. The book forms I use are chosen to best serve content, sometimes that leans towards “highly crafted,” sometimes towards simpler structures. I am interested in the most efficient, direct means to convey content through material. Image-making techniques include painting, printmaking, photography, drawing, collage, and more, and are usually paired with poetry.

Interior Landscape began as a response to Sylvia Plath’s journal entries on the subjects of writing and motherhood but grew to encompass artist-mothers everywhere who strive to accomplish but who wrestle with myriad infringements on their thinking and doing.

What is book art? Book art might indeed look like a book and it usually references the book form in some way, but this art medium doesn’t have prescribed parameters. It allows for a broad range of expression through a unique combination of text and/or image, sequence, and structure, and it does something a “regular” book just can’t do. It “requires” the reader to engage with it in a different way.

The kaleidoscope functions, but the light and therefore the beautiful patterns are obscured by the miniature book, which houses a poem about an immigrant boy with overlooked learning difficulties. Part of A Year In Books.

Academics in the field love to talk about “the reading experience,” which is, logically, an important part of book art: we don’t usually make these objects to sit on shelves. (Although there is highly sculptural book art that does just this. It’s hard to pin book art down to any one definition.) Admittedly, “the reading experience” is a rather off-putting way to simply describe how a reader deciphers these objects. Unlike 2-D art, in book art the reader/viewer (usually) must manipulate the object and its contents, resulting in an “experience” that is, as a rule, very unlike reading a “normal” book.

Chronicles of Migration invites viewer participation to create narrative content. This accordion book contains 16 extractable image cards, which, when removed, reveal a series of questions (Who, What, Where, etc.). The reader/viewer is prompted to reorganize and interpret the image cards, according to the questions, “to tell the story or stories about migration, historic or contemporary.”

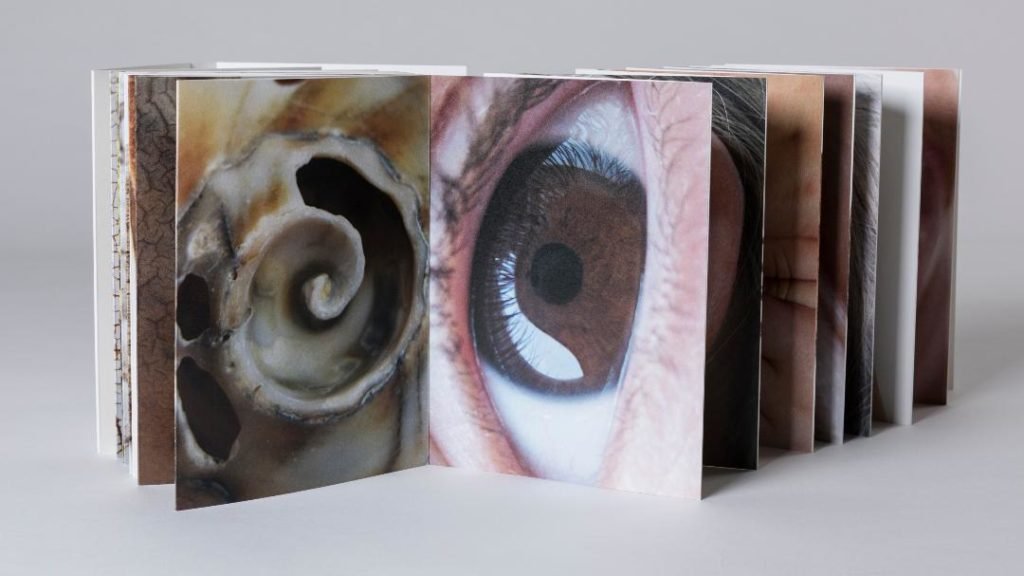

Close-ups are paired in a series of photographs by the artist to illustrate similarities between objects from the natural world and her young children.

Academics also enjoy splitting hairs over the sometimes-interchangeable terms: “book art” (generally, more object-based) vs. “artist’s book” (generally, more conceptual). But a hotter debate in book art regards Art vs. Craft. Doesn’t any art form require technique and technical skill (think: music, oil painting, clay sculpture, poetry)? Book art is no different. Craft is a tool used to get from Point A (idea/concept) to Point Z (physical/material expression of this idea). Without content, it’s hard for any medium to move past pure craft.

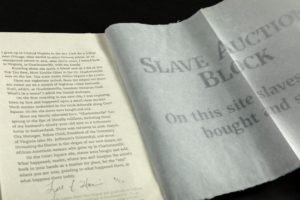

What happened, reader, where you are? What happens there today? asks the artist’s book, Site. Inspired by her discovery of a slave auction block in 2015 on the first morning in her new town of Charlottesville, VA, Harris grapples with US history in a project that points to the past and brings the reader into an awareness of the present.

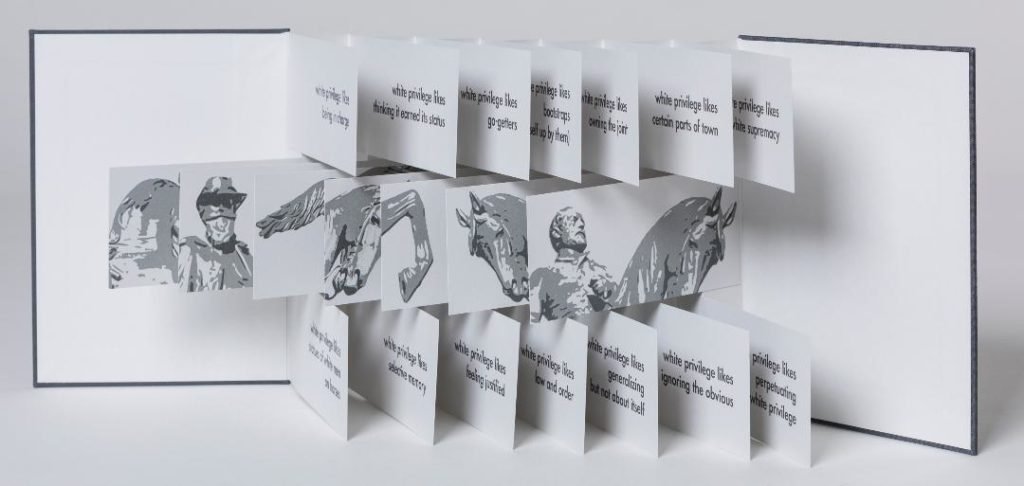

Statements unfurl in this flag book structure that seeks to reveal problematic aspects and challenge assumptions of ‘white’ thinking. Images are photographic details of statues of Civil War generals taken by the artist on Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA. Harris moved to Charlottesville, VA, in 2015, just as the debate over the Civil War statues was erupting.

“Is it illustration?” is a question book artists inevitably get. No, it isn’t illustration. But illustrated books are part of what “came before” (think: early 20th century French publisher Ambroise Vollard’s pairings of art and text in Livres d’Artiste or Russian avant-garde books, such as those by Natalia Goncharova), and illustration can still be a component in today’s book art. (There go those pesky definitions again.) But this is a medium where the material components combine to create a faceted, more comprehensive and potent language to express content. Importantly, subject matter determines form in this versatile medium.

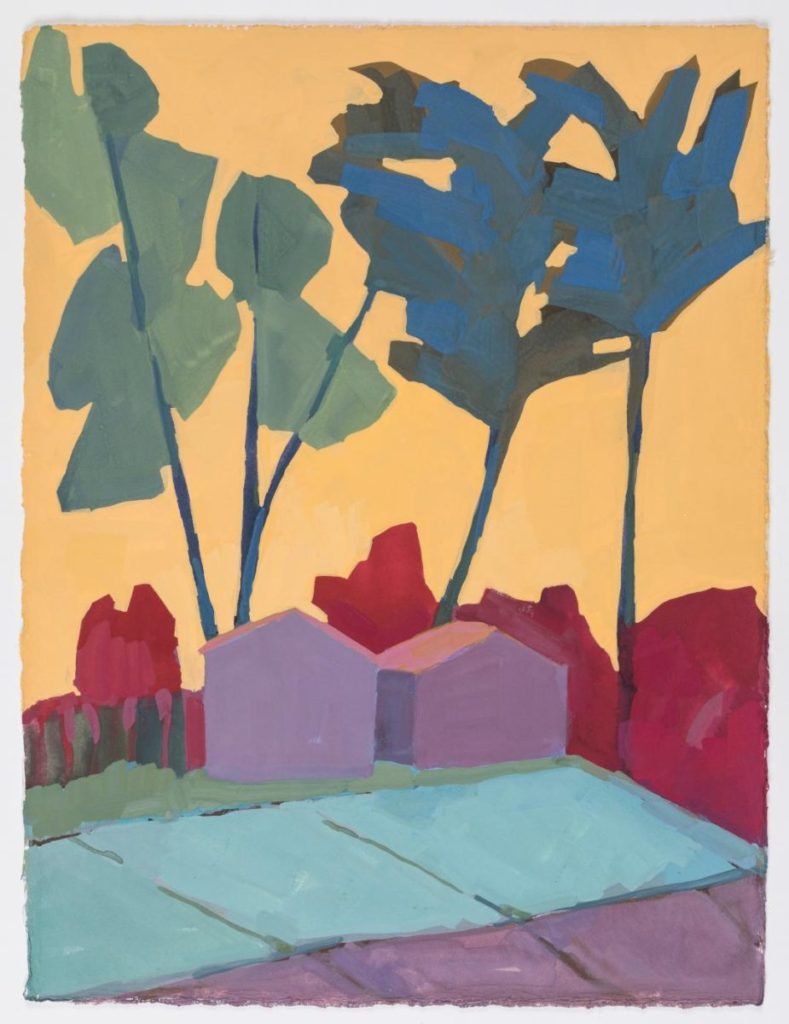

Sometimes my paintings are in the service of book art and sometimes, like these, they are part of a body of 2-D work.

There are many “genres” of book art, from altered, very material or sculptural “bookworks” (Maya Lin’s Atlas Landscapes, Anselm Kiefer’s book sculptures, Colette Fu’s pop-ups, Julie Chen’s games) to highly conceptual “artist’s books” (a seminal artist’s book: Edward Ruscha’s 1963 Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations), and everything in between. There are as many forms of book art as there are book art practitioners.

Drawn to work that is both (formally) harmonious and narrative, I find inspiration in these and others, such as Kara Walker and William Kentridge. I often return to painters like Giotto, Rothko, and Mark Bradford. Like any artist and writer, I have a mental archive that informs my work: Joseph Cornell, Martin Puryear, Charles LeDray, poets Anne Carson, Sharon Olds, Natasha Trethewey, and M. NourbeSe Philip, and dozens more.

Many book artists are attracted to the material aspects of this medium, which often involve working with old technologies, such as papermaking or letterpress printing. (Why do things the easy way?) It’s no coincidence that book art’s rise over the last decades coincides with the digital age. As we risk losing this touchstone cultural object, an art field has cropped up that produces highly conceptual or highly crafted book objects.

Happily, for book artists in the Charlottesville area, there is a Center for Book Art, a program of Virginia Humanities, which houses several old, but functioning, pieces of equipment.

From March 8-25, internationally known letterpress artist Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr. will be the Center for the Book’s inaugural Frank Riccio Artist in Residency.

Together with artist Veronica Jackson, I’ll be joining Kennedy in conversation about his work at the Virginia Festival of the Book event on Sunday March 24 from 12-2:30 pm. Prior to the discussion, Kennedy will hold a demonstration on the letterpress.

Share this post with your friends.

What an interesting article! Wish I were able to attend the festival

Inventive, beautiful and profound work!

This is such a beautifully written account of Book Art for both the newbie and the seasoned Book Artist. I love seeing how we can bring these conversations into spaces that previously did not have them. Lyall’s work is amazing and I’ve had the pleasure of seeing many of her books up close and personal. The bridging of art, books, culture, history, poetry, and analog techniques has intrigued me since learning about this art form and Lyall’s ability to connect her gifts, talents, and passions is both inspiring and motivational. Kudos for the Center for recognizing the need for this in our society and supporting those of us who do this work.