The sun was warm and bright as we pedaled our way along the new Ring Road encircling the city. On its outskirts we saw many families working there in the Kathmandu valley, women weaving mats, others rhythmically washing their clothes by hand, beating them on the rocks and stretching them over the banks and stones to dry. Little children were everywhere. There were children carrying children, neatly tied onto their backs with brightly colored cloaks, some babies naked, crawling alongside their mothers who, though busily working, were not too busy to look up in amusement at such a caravan of motley westerners as were we, such obvious newcomers to this primitive metropolis. The Kentucky farm girl in me, raised by those rooted in conservative, rural racism, felt as if I had landed in a dream world where I might find my way to a stronger, truer life.

In January of 1982, still in my twenties and determined not to land in some ordinary doctor’s office at the end of medical training, I was participating in an international public health elective. I had, after all, landed in the depths of Mississippi, at the University Hospital in Jackson, to become a doctor of all things, a doctor who still believed I could make a difference in this world…a doctor who back then thought I could fix it all, given the time and space of life before me. An important piece of the puzzle of my life lies here in this early vision of working around the world in some of the neediest spots of humanity where my children and I would thrive, in different cultures, learning their languages and their ways. Though I had only given birth to one child at the time, still my children were an integral part of that vision. And though I didn’t know it yet, understanding and healing my own broken soul was an important, yet still subliminal part of my dream.

Nearing the end of medical school, I realized my studies and professors were not helping me to land where I intended to go, except for one charming old physician, Dr. Tom Brooks, chairman of our Preventive Medicine department. Having worked internationally himself many years prior, from Thailand to Trinidad, he smiled at my curiosity about international health work. Looking over his glasses, he quizzed me in a warm, yet professorial voice. “Does your husband share your enthusiasm for working and living out of the country?” I couldn’t say he did. I could only say that my own passion for working in simple, less affluent cultures was one of the main reasons I had gone to medical school. He hesitated, nodded, and set himself to placing me in an equally exotic spot in the world as he had worked as a young doctor. Being a friend of Carl Taylor, the head of international health in Baltimore, made it easy for him to make me a member of the Johns Hopkins’s medical expedition to the Himalayas that year.

Young mother though I was, and more in love with and responsible for my son than I had ever been for anything, still I signed up, believing all the necessary accommodations could be made for this crucially important mission, crucially important to help me decipher where best to put my energies within a career in medicine. My first child, Zak, was just two and a half when I went to Nepal in 1982. I dreamed of him every night on that medical expedition, yet rarely regretted having gone to participate in the mapping of yet uncharted villages, the setting up of our clinic and camp there by the Kali Gandaki river, the manning of the microscope by the medical student from Mississippi who was the only one among us already quite versed in each of the intestinal parasites we would find in those third world villagers.

We had planned for Zak to stay with his wonderful old babysitter Granny, until his father could get settled into his work in Vancouver and send them both plane tickets. As a rock-and-roll musician, my husband had landed work in a Canadian nightclub. I didn’t know him well enough then to predict those tickets would never materialize. Actually, in some deep space within me, I may have known there to be inherent risk, but I was holding the veil tight to my vision those days. In some superficial realm of awareness where I mostly lived those days, I believed the three of them would have those weeks to themselves so that I could have time away, on expedition, to cultivate my dream of a different life, which included each of them, but especially Zak. The one thing I was perfectly certain of was that I would be holding Zak in my heart every step of the way along that distant path I was planning to take.

After a two-day flight, having laid over in Delhi, Bob Davis, the leader of the expedition, pointed us toward the scene beyond our little Royal Nepalese plane, as he said in his characteristic, nasal voice, “Look out your windows to the west, guys. Those aren’t clouds.” We were flying in from the south. The earth’s most massive and majestic mountains were showing us their snow-covered southern faces, glistening pink with reflections of the sun just over the horizon. We were in the East, many of us for the first time and on the brink of an experience we still could hardly imagine which would color all of our future career decisions.

Young internist Henry Taylor, one of Carl’s sons, was the trek physician. He had bicycles waiting for us at the airport. To descend from the plane where we had been cramped into tiny seats for two days and mount a primitive bicycle to stretch our legs as we biked into Kathmandu redefined refreshing for me. The bike ride from the airport to the heart of Kathmandu awakened all my senses. That first day in the East was an incredibly poignant introduction to daily life in this third world we were entering. My heart and mind were wide open, in an ongoing though mostly subconscious search for that better, slower paced, more grounded world in which to raise my children.

Our hotel had hot water when the electricity worked, which turned out to be about half the time throughout the city. The time had come to be cautious with all we ingested. We washed up, filled our water bottles with boiled, then iodinated water, but did not linger long in our fairly fancy Ambassador Hotel.

We quickly took to the streets that were lined with many tiny dark wood-fronted stores and stalls with barely enough room inside for one person and his or her many piles of spices and herbs, vegetables, fruits, or peanuts to sell, pungent incense wafting from the windows. No neon signs heralded these establishments. In the center of the city, the streets were filled with throngs of relatively small brown men, women, and children whose pockets and pouches were stuffed with souvenirs to sell to Westerners. Not at all bashful to demonstrate their handmade musical instruments, Gorkha knives, and prayer wheels, they tried to sell us them all for a “very cheap price.” Far more was asked than expected for these items, as bargaining was part and parcel of their street sales, the transactions accompanied by sweet, haphazardly toothy smiles. Then a leper would appear, dragging himself along the street with outstretched mutilated hand, begging for his supper. Such evidence of infectious and vaccine-preventable disease was in every Kathmandu crowd, a moment-by-moment reminder of why I was so drawn to international health care.

All manner of brightly colored, hand-woven woolen sweaters, Tibetan carpets, trinkets, and baskets were displayed on both the ground and second floors of some storefronts. Narrow streets opened onto town squares with old pagoda-styled temples in the middle, also garnished with both brightly colored and earth-toned blankets and rugs for sale. The smoky smell of cooking fires pleasantly permeated the air. Cars inched their way through the crowds, sounding their horns freely to avoid hitting people and cattle, for killing a cow, no matter if unintentional, was criminal in Kathmandu.

Bicycles and fringed rickshaws made their way through the crowded streets as well, ringing their bells, the drivers’ hamstrings much more prominent than any of ours. The barbers cut hair in open air. I basked in Kathmandu’s primitive simplicity, feeling I had stepped back into a saner age. Around dusk, everyone began to slowly trickle away, heading home before the streets darkened since the electric streetlights were as likely as not to not illumine any given night.

Three days we explored this ancient Hindu city. Henry had studied the monkeys of Swayambhunath temple for National Geographic a few years prior. I hope to never forget the day I was there with him calling the monkeys by name. To see those agile critters scamper down from their tall trees and sculptures to jump onto Henry’s arms and shoulders to pick at his beard and face felt such a privilege, to be with a person who straddled two cultures so gracefully and well.

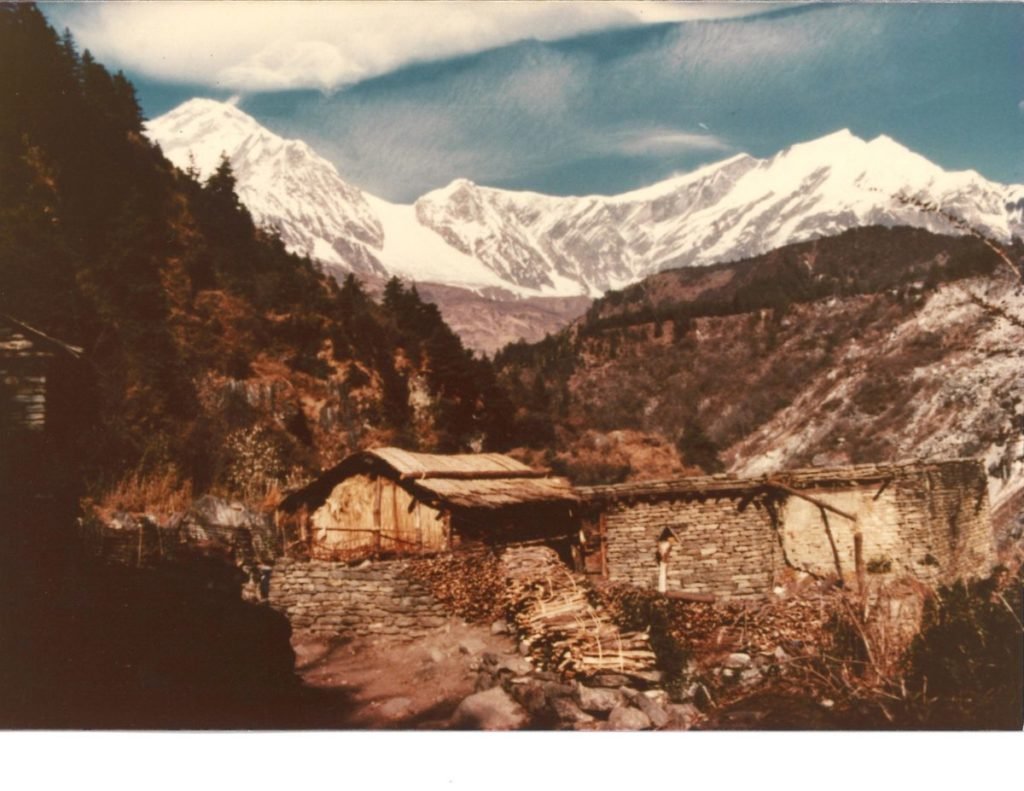

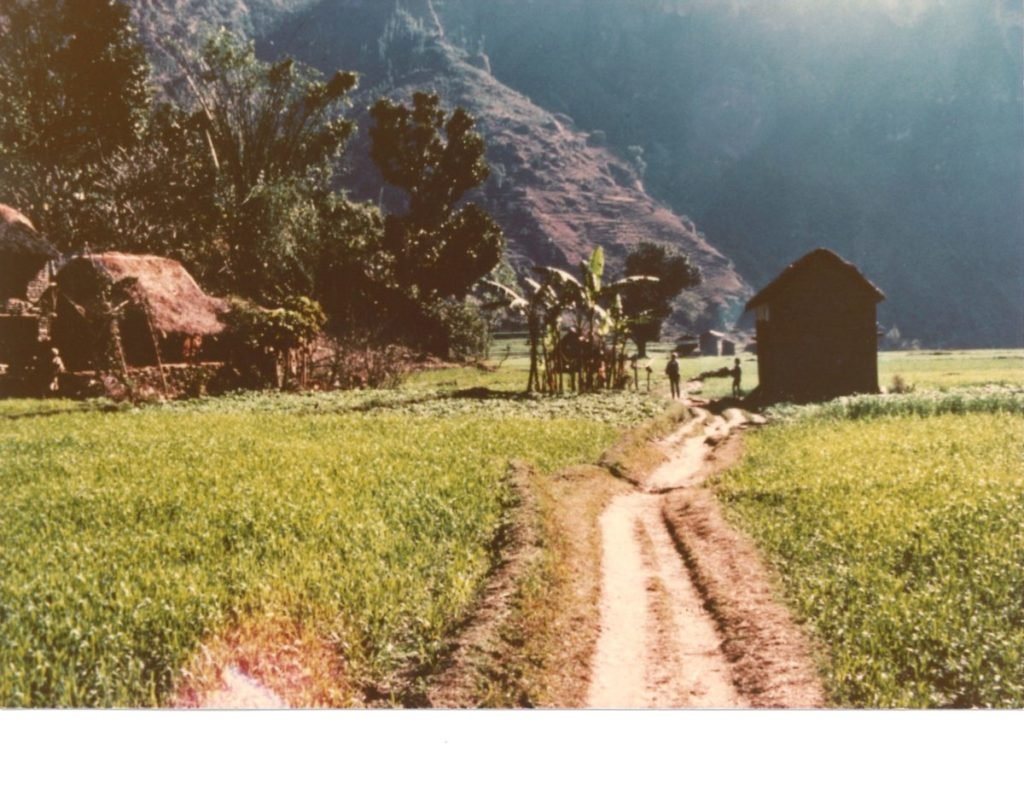

Our first two weeks in Nepal were designed to give us a cultural acclimatization to the country and its people. After all of our visas were approved, we took a bus from Kathmandu to Pokhara. From there the trek began. Each of the fourteen days, we hiked several miles toward the Tibetan plateau, a few thousand feet up one mountain range and down the next, through their rustically vibrant villages, along an old stone Tibetan trade route. The first night out we camped on the south side of Naudanda, a village at the crest of a 2,000-foot ascent from the valley beyond Pokhara, where we rented a farmer’s terrace, about twice as wide as our tents. Breathing the fresh mountain air while setting up and taking down camp on the sides of these hand-sculptured hills engraved lasting memories into my mind. The mountains appeared quilted, one terrace of bright yellow flowers, the next verdant winter wheat, others striped the quilt brown, lying fallow. Their familiar, rugged, snowy peaks shone in the distance, soft pastel palettes of sunrises and sunsets their breathtaking backdrops. As I marveled at the tapestry of this idyllic life, I felt so sure I was exactly where I was supposed to be in the world.

Also etched there in my mind, though less prominently, are memories of retching and explosive diarrhea in the ice-cold night, after the dreaded sulfur burps began to rise, a few days after a giardia cyst or two slipped through our careful water treatments. My own gastrointestinal symptoms never lasted long; some of my fellow students suffered for days on end. Those nights after hiking into the higher altitudes, to Ghorapani at 10,000 feet, everyone’s noses dripped like faucets.

Henry occasionally encouraged us to carefully splurge a little by making ourselves a washtub of warm water with some of their precious firewood to wash some of the dirt-creased areas of our body at least partially clean, especially nights in the higher elevations that felt so frigid. Henry was always aware of the scarcity of their resources and helped us remain mindful to use them ever so sparingly. How wonderful a little warm water on a wet cloth was to wash our dirty faces those freezing nights at altitudes higher than most of us had ever been.

Several days into our trek up toward the Tibetan plateau, I dreamed of Zak, febrile, standing in a playroom full of toys, crying inconsolably, wanting only his mommy. Temporarily tortured, feeling nearly helpless, I didn’t know what in the world I was to do, so far away from my son, with no means of communication. Or was there?

I had heard talk of a telegraph in some of these remote high mountain villages. The mother in me was desperate to get word to my son. It turned out I was not the only one in our group at that moment with special needs, so we split into two. Henry’s wife, Nancyellen, in her fifth month of pregnancy, welcomed taking an alternate path that would allow her to rest for a couple of days. So while half of the group trekked on toward Muktinath, the rest of us settled into a beautiful town named Marpha, nestled into a northwestern valley of the Annapurna range. From there, Stu and I took yet another detour to find a town with a telegraph.

Jomsom, a desolate outpost of a Himalayan hamlet, was also a checkpoint with a police station, a post office, and a telegraph! I hiked hard that afternoon, my mind propelling me like an arrow on a young mother’s mission. The harsh Himalayan winds were not in our favor; still we arrived before closing time, four o’clock on their Sunday afternoon. First I went to the small box-like building with Telegraph written on the sign above the door. Upon entering its front dark room, I encountered only a few men huddled around a fire and asked with a still hopeful voice, “Telegraph?” A very disappointing shaking of their heads was their reply. Somehow, though their English was no better than my Nepali, I came to understand their telegraph had been broken for a week. They were waiting for someone from Pokhara, a seven-day hike away, to come up and fix it. In response to my persistent questioning about communicating with my sick little son back home, one of them said, “In an emergency, the police might help.”

“And the post office?” I asked. It would be closing in ten minutes and was back across the river. I mumbled my thanks, then ran to the post office in two minutes, only to find it already closed. My spirits sinking, still I dropped my letters in the feeble-looking drop-box outside, with no confidence they would get any farther. My last-ditch effort was back on the other side of the river again, now for the third try, with the police.

I knew the importance of speaking the language of the place where one is, but my Nepali was meager, and I desperately needed their help. So I used the universal language of a mother’s tears and trembling voice as I asked the policemen inside to please help me. They seemed disinterested, yet likely, our language barrier was really all that separated us. Knowing there was a little boy in the world who loved and depended on me above all others and hearing the telegraph ticking away in the background, I took a seat with them by their fire, where I sat and determined to stay until any one of them was willing to help.

Lightheartedly in walked Stu, who had come with me to Jomsom to purchase medicine for the group. He quickly intuited the situation. Seeing me sitting, huddled silently in the circle around the fire with these Nepalese strangers, Stu approached me and said he had found someone in the village who could help us. He had found a bilingual health assistant. Within minutes, a cheerful Nepali arrived, explained my dilemma to the men around the fire, and went to the back to get someone who could take my telegraph.

With an air of warmth and confidence, out walked an older man with long-suffering, smiling eyes. He handed me a piece of paper on which I wrote, “Must know how and where is Zak. No access to telephone. Will call in Kathmandu. For now I’m simply sending ALL MY LOVE.” He told me the machine had just closed down for the day, but that he would send my message at six o’clock the following morning. He seemed so sincere. I left not thoroughly convinced of successful communication, but somewhat satisfied at having given it my very best effort, and hopeful an answer might be waiting when I got back to their capital city.

I had started fasting one day each week for Zak when he was three months old, when the summer break of medical school was over and the time had come to return to school. I knew I would have to be away from him a lot. I believed I needed a strength far more powerful than my own to watch over my son. Once, under his father’s watch, when Zak was a tiny little boy who had just begun to sit alone and the horse jumped over him out in the field, I was sure, beyond a shadow of doubt, it was my fasting that had kept him safe. It felt as if I had made a pact with God, who had fully agreed to watch over my boy in exchange for my sacrifice.

In Nepal, in these fairly extreme circumstances, I had let go of that tradition, but at Jomsom, I started it back, believing again that fasting might be my best hope for spiritual protection of the one I loved most. Feeling stronger now a week into the trek, one day each week without food would not hurt me, and it would hopefully help my boy. I prayed hard each fasting day that God take care of my son in my absence.

Coming from the Southern Baptist Church of Brandon, Mississippi, that taught conversion of the entire world to Christianity, I arrived in the East with a cross around my neck. Within a few days of watching the sweet Nepalese, I realized the absurdity of thinking they should be Christian. At first I put the cross under my shirt, then took it off altogether. But I never quit praying for Zak.

On our way back down toward Kathmandu, we were all feeling stronger. Etched deep into my heart from that leg of the trek is the night back down the trail when we slept at Tatopani, named for its famous hot springs. That evening I sat naked by a fairly fat Nepalese lady in the river at the edge of the bubbling hot water, scrubbing my body like it had not been scrubbed for two weeks. We had little language in common, yet there we sat literally naked together as she motioned for me to wash behind my ears, where I was still apparently quite dirty. Then her brown hand came up to touch the spot on my neck, and she giggled.

Pathologically shy myself, I nonetheless felt emboldened from the experiences of the past fourteen days to sit there with her, quietly soaking that moment up into myself. The timid grin on my face reached out to her too as a cross-cultural bond was formed. Though our languages, homes, and traditions were all so very different, women like to get clean at the end of the day, and how better to do it than in a hot spring in the high Himalayas, which she was cheerfully sharing with me. That night I felt more at home within myself than I remembered, bathing there naked in the river among those equally naked Nepalese women.

Share this post with your friends.