Ten years after graduation, at seven a.m., Sunday morning, I round the corner to my office and nearly stumble into a distraught family in prayer. Six adults, seated with their heads bowed, listen as a Catholic priest, and a Baptist minister, beseech God to help them. A teenage boy leans against the doorjamb, listening, but obviously uncomfortable.

In a second, I decide the clergymen have the situation under control and proceed directly to the ICU to learn what has happened. As I guessed from the looks of the people in my office, the news is tragic.

The nurses gathered around Cindy turn toward me when I walk through the door into the unit. I stop at the desk behind the thick glass window surrounding the nurses’ station, thankful it is there for me to escape to while I study the few pages of her chart lying on the desk.

Around four o’clock this morning, seventeen-year-old Cindy and her eighteen-year-old fiancé, Tom, were driving home after their senior prom party when his van went off the highway and rolled over. At the moment of impact, Cindy’s cervical spine fractured at C-5, and sliced into her spinal cord. Although she was handled delicately by the rescue volunteers when they removed her from the van, her spinal nerve tracts at the level of the fracture have been severed by sharp pieces of bone. She is a quadriplegic, paralyzed from the neck down. She can flex her arms slightly toward her chest. Perhaps slightly more function will return in a week or two when the swelling of the cord subsides.

Since age five, Cindy has been treated for scoliosis. Eighteen months ago, a two-foot steel rod was placed up through her vertebrae to bring them into alignment while she finishes growing. When the van turned upside down, the lack of flexibility in her lower spine hyper-extended Cindy’s head, with enough force to fracture the fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae just above the point where the steel rod stopped.

Her head is in traction, held by a steel frame screwed into two holes bored into her skull. I know this frame is routine; the five pounds of weight pull her head toward the top of the bed and relieve pressure on the cord to keep the bone pieces from doing further damage. I know also that even though it accomplishes the crucial immobilization of her neck, the frame adds to the pain coming from the fracture. She cannot feel anything from C-5 down, but Cindy’s body above that level is still neurologically intact. I say her name aloud to myself, once, softly, take a deep breath and walk to the side of the bed to talk to her.

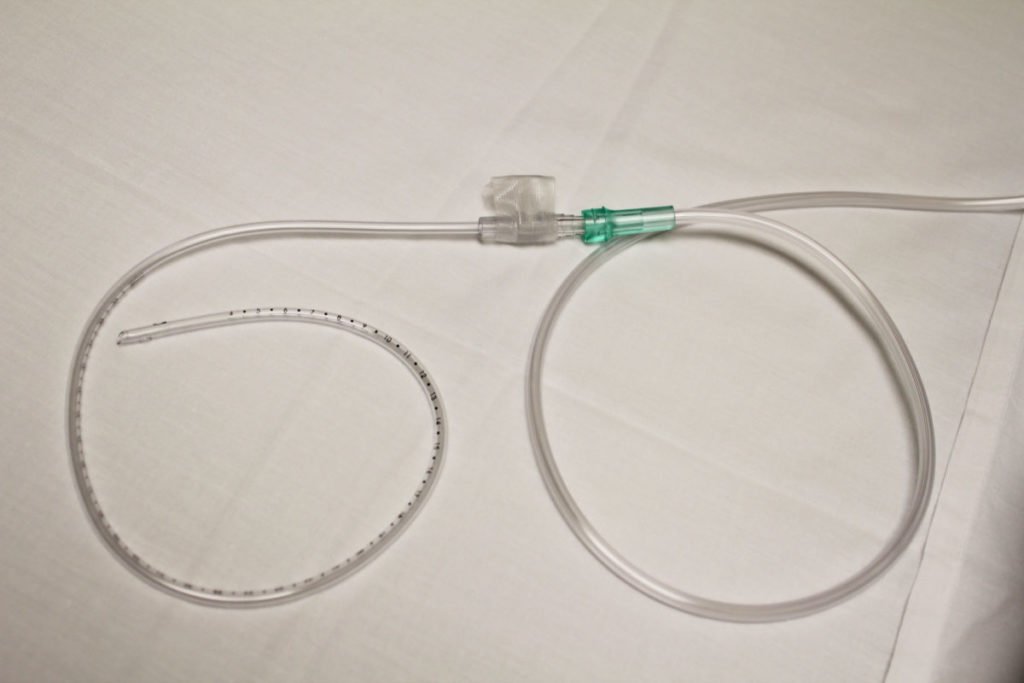

Given her position and the immobilization of her head, Cindy can see only the ceiling and within the periphery of her eye movement. If we stand at the foot of her bed, she can lower her eyes to look at us, or see us from the side when we stand beside her at waist position. She has an endotracheal tube in her left nostril curving down into her windpipe to insure our ability to breathe for her should the traumatized nerves and brain cause her to stop. Because of the tube’s placement and inflated cuff at the end, she cannot speak.

“Cindy? Can you hear me?” She closes both eyes. I take this to mean yes and tell her we’ll be with her today and every day she is here. Her thin blond hair is wet and pushed back over the top of her head. Circles of it have been shaved around the metal prongs in her skull. A small bruise has risen over her left eye. She looks like a young child, to me, here on her back with her pretty face swollen, her slim, numb body creating minor hills and valleys in the white top-sheet, yet, she is engaged to be married. She wears the little diamond on her left hand.

Dr. Chesler, the hospital’s one neurologist, has entered the unit, back from the X-Ray department where he has been assessing her films. He looks very tired. As he walks through the door, he spots me and shifts his eyes around the room until they focus on Cindy. He walks to her bed.

“Hi Cindy,” he says firmly, and takes her hand. I notice that her fingernails have been bitten down to the quick on each finger and think suddenly that she won’t be able to move her hand up to her mouth to bite her nails anymore. Immediately I wonder why I’m thinking this way and will myself to stop thinking at all for a moment. I’ll just listen to what the doctor is saying. When Dr. Chesler asks Cindy if she has any pain, her blue eyes stay wide open. She moves her eyes toward the ceiling. I assume that means no. The doctor looks at me and I realize he wants to talk to me privately and I walk with him to the desk inside the glass enclosure.

“We’re going to need one or two nurses on each shift just for her,” he says. ” Do these nurses know how to take care of a spinal cord injury?”

Dr. Chesler has been at our hospital only a few weeks himself and hardly knows any of us. I tell him that most of them probably don’t, but that I am experienced with spine injured patients and I will teach them. As I say this I wonder just how I will teach them, and how long it will take.

I’m the nursing coordinator for Critical Care in a two-hundred-twenty bed community hospital in a small city in a mid-Atlantic state. An hour ago, I arose with my five-year-old son, helped him dress, ate cereal and toast with him and drove him to his weekend babysitter’s home for the day. I’m single, not divorced, but single and the sole support of my child and myself. All the way to work I’ve been picturing my boy watching cartoons in the babysitter’s living room. I can hear his laugh as Sylvester the Cat skids around the living room door in the cartoon on TV.

Eighteen months ago, I was hired to open and staff this nine bed Surgical ICU, and even though I’ve cared for patients with spinal injuries before, none of the staff nurses and aides have any experience with them yet. Most of them have never seen someone who is quadriplegic, have only heard of people having this injury. I wonder what they understand or remember about the anatomy of the spine, wonder if they know to watch for vomiting and respiratory failure. Several of the nurses from both shifts are standing around Cindy’s bed, looking at her, but saying nothing. They will have to learn to care for her by watching me. How much of her care will I have to do myself every day in addition to my regular job as coordinator? I’ll have to explain as we go along with each procedure.

I ask Dr. Chesler how long he expects Cindy to be in ICU, and he estimates at least two weeks before she can be transferred to a rehab facility. We discuss her care, a schedule for turning her, the particulars of her medications and intravenous infusions. I make notes. I ask him when she will go to surgery to have the pieces of her vertebrae wired together.

He answers all my questions clearly and patiently and explains that right now we must be concerned about her breathing since the intercostal muscles between her ribs are paralyzed. He reminds me, and himself too, I gather, that the diaphragm will function on its own, triggered by the brain’s respiratory center to keep her breathing, but her lungs can easily accumulate fluid and become infected. In less than a day Cindy could develop pneumonia. I try to sound knowledgeable, try to reassure him that in this new Surgical Intensive Care Unit, in his new hospital, the nursing staff will follow his directions and work diligently with him to keep Cindy alive, and to preserve her remaining function.

“It’s the worst injury known to man,” he says quietly as he goes out the door, “throughout history.”

I nod, trying not to feel overwhelmed, and ask myself what I really know about this injury. I remember I want to tell the nursing staff that it usually happens to young, physically fit people who never expect to wake up paralyzed. How do you tell a seventeen-year-old her bowels won’t move anymore without help? That she’ll never walk, never point her finger again. This is why the family and the priest and minister were praying so fervently in my office. We need all the help we can get. I hope I can think of the right things to say to this girl. The other nurses look scared, and I wonder if they will be able to hear, over their fear, the instructions I’m about to give. I remind myself, though, they are a sharp group of women who’ve risen to the occasion of delivering excellent care more than once in astonishing situations. They work well together and are respected by the medical staff. I decide that my own insecurities are the real problem I have to overcome. I’ve been hired to be the expert here, and Cindy and her family need our most professional work. We’re the most skilled nurses in the hospital; we make intensive care possible. We have to do it, and do it well. There is nobody else.

Cindy’s parents are divorced and both have remarried. Her mother and stepfather are Baptists and her father is Catholic, hence the priest and minister in my office. On this first day of their crisis both families are clinging to whatever support is near. During the brief moments I was in my office, I noticed the Cindy’s mother was physically leaning on Cindy’s stepfather. The group is now standing in the hall beside the door to ICU. I follow Dr. Chesler out of the unit and stand by while he talks with her family. I‘m used to being present when bad news has to be given to families, and find myself wondering if anyone is apt to faint, which occurs sometimes when the next of kin realize what has happened to their loved ones. I look from one to the other, at their ashen faces, at their tears, and know that all of them, including her younger brother and her boyfriend, will need a great deal of support.

Later, when I meet with the nurses, I explain that each time we speak to her family members we must be comforting, evaluating, teaching and setting limits. Too many visitors will exhaust Cindy of her precious life’s energy. As the hours wear by, I wonder how these parents can still be standing, wonder how I came to be here in this place, at this time, with them, with their daughter, with this doctor and these nurses.

I go home exhausted, two hours late after orienting the nurses on the evening shift to her care. My five-year-old son jumps up and down with happiness when I arrive at the babysitter’s home. We go home and have dinner together and watch Disney cartoons on Sunday night television. During commercials, when he dashes across the living room, I take delight in the movement of his willowy body. When he drops to the carpet and rolls himself over until he stares up at our dog’s chin, and she licks his face and he giggles, I remind myself that life does go on with gusto in some parts of the world, in this very center of my existence.

***

A week passes and Cindy still can’t talk. The traction and its frame were removed during surgery, but she has a tracheostomy, a temporary opening, in her throat to let her breathe. She has been moved into a private room on the west side of the ICU. The night nurse tells me Cindy seems depressed. This is how we talk. Everything is an observation without emotional connotations or conclusions. Right after morning report I go into her room and close the door. Cindy continues to express herself with her eyes. Today they looked desperate and angry. A multitude of clergy, both Catholic and Baptist, have been here already and have left their memorabilia of Christianity hanging all around the room. Pictures of Christ have been taped to the walls and several crucifixes laid on the bedside and on the over-bed tables. Bible verses in tiny cardboard frames dangle on strings from the ceiling and from the top of her bedside curtain-—I can’t imagine how someone was able to get them up there.

Through the glass window in front of her bed Cindy can usually see out into the rest of the unit, and watches us care for other patients and generally work around the room. Staff members slip in and out for a quick hello. But now these religious relics are obstructing her view. Physically they are in the way, and psychologically they intrude on her personal space and undermine any small amount of control she has of her life. In a few minutes of well-meaning helpfulness, the clergy have hurt her by crossing boundaries. There are artifacts everywhere, too close to her person, too close to her eyes. She can only stare at the ceiling to avoid them. Cindy looks my way when I walk through the door to her room and close it behind me. Her blue eyes hold me as I move toward her. She looks anxious and very sad. When I reach her bedside I take her hand and speak without hesitating.

“Cindy, you must be having lots of different feelings right now.” She shifts her eyes away from me and looks toward the glass window.

“Aren’t you, Cindy? Now that this has happened to you?”

She nods, closes her eyelids.

“I know you can’t talk now, Cindy, but you will pretty soon when this breathing tube comes out. I just came to say that its only natural that you’d have a lot of different emotions, powerful feelings.” She nods again and tears pour out of the outer corners of her eyes.

My words keep coming. I haven’t rehearsed this.

“It’s okay to be angry, Cindy. It’s okay. Whatever you feel is all right to feel. It’s okay to feel sad or to feel furious over your injury.”

She focuses her eyes on the religious paraphernalia. “You know, Cindy, it’s okay to be angry at God too.”

Her tears continue to stream. She is sobbing and beginning to cough through the tube. I keep reassuring her that she’ll be able to breathe, that it is okay to cry.

“God can take it if you’re angry, Cindy. Anyone would be angry in this situation.”

The room feels so cluttered and close.

“Do you want me to take some of these things out of here?” I ask.

Both her eyes close at the same time. I realize for a second that I might be addressing my own needs. I haven’t expressed to anyone my own feelings of suffocation when members of the clergy come in when we’re busy and hang around for hours until we ask them to leave. That concern vanishes when I remember that I have come into Cindy’s room this morning because I could see she was very tense and with a desperate look in her eye. I can’t do anything to reverse her paralysis, but I can try to make her comfortable. That includes her mental and emotional comfort.

As I remove each item I ask her permission. “This? This one?”

Her eyes are blinking steadily telling me “yes, remove it,” and I continue to put them away in a drawer or into the waste basket until I reach for a tiny gold cross on a chain which her father has left. She stares at the cross intently.

“Okay, I’ll leave this.” I realize I am verbalizing for her. It seems to be helping. She’s stopped crying, seems more relaxed. The room is beginning to seem more spacious. I hope I’ve turned it back into Cindy’s room, have given Cindy some control of it. There seems to be so little we can actually give her in the face of her crisis, but today I am able to give her a little space. My arms and legs can move, and I am willing to lend them to Cindy, for a while. She can count on me to respond, and direct me to tidy her room. With my hands, she can gather up all the items she doesn’t want and send them flying into the trash.

In a few minutes, after the room is neat, I ask Cindy if she will let me turn her over to massage her back. She consents with her eyes and I rub lotion into the wrinkled skin of her firm young back and smooth her sheets, position her on her right side and comb her hair. When I leave the room she seems to be half asleep. I whisper that I will be back in a little while. I think she believes me.

***

Three weeks later, Cindy has been transferred out into the main ward of ICU and has begun physical therapy. Her lungs are still filling with mucus, though, still a constant problem. One afternoon, I stand beside her bed suctioning her trach when she stops breathing. The tracheotomy tube, stainless steel and extending three inches down into her windpipe is still in place and I pull the oxygen mask off it and cover the opening with my mouth and begin to breathe for her. Over my shoulder I yell, “Need some help!” and two nurses in white and a nurse-aide in scrubs come immediately to join me. There’s nothing any of them can do until I ask for relief, so they stand beside her bed encouraging Cindy to breathe and I huff into the tube, stopping every few breaths to look for movement of her chest or to lift an eyelid or check a pupil. Her color is maintaining as pale white, but her lips are pink and that is a good sign that the oxygen I’m breathing into her is getting deep into her lungs and into her blood.

I huff and huff into the trach and count silently in my head—has it been two minutes? three? We are together on the razor-sharp ridge of a mountain, this little bird and I, and she will fly across the deep valley and disappear if I stop mixing my breath with hers. It is our job here in this room to keep her here with us if humanly possible. The voices of the other nurses are background noise now and just when I ask one of them to take over breathing for her, Cindy coughs back at me, rattling the trach tube and blowing green mucus out of it onto the front of my uniform. I stop resuscitating and step back. The other nurses are cheering for Cindy. She sucks in a deep automatic breath as her diaphragm lowers itself and blasts another moist cough in my direction. My face is sprinkled with her mucous, but I’m smiling, and find that I can now pull in a deep breath for my own use.

Cindy’s back now—lips and face flushed, still coughing a bit, clearing the pipes.

“Oh . . . what happened?” she rasps through the trach tube, and we tell her. Betty, the nurse’s aide, begins to wash Cindy’s face with a clean white cloth and the others come close and change her gown and comfort her with their touch and words, then replace her oxygen.

I go into the bathroom where I wash my own face with a washcloth and soap and wash my uniform off and scrub my hands and dry them. Had I pulled too much oxygen out of her with the suction apparatus, or was she on the verge of respiratory arrest anyway? We’ll never know, but for now Cindy will stay in the strict routine of ICU where day-to-day we can keep the treatments going.

***

In a few weeks, she’ll go to a rehab hospital, a four hour drive north, and spend months there learning to use modified utensils to perform daily living activities using the slight forward flexing motion she has with her arms. Every possible stroke of movement of which her muscles are still capable will be exploited to increase her independence. It is especially important that she will learn to pull food off the tray toward her mouth in a large bent spoon fastened to her wrist, or with other instruments meant to facilitate eating, and to comb her hair a few strokes with an over-sized comb. She will be able to sit upright in a wheelchair she can operate electronically by blowing into a tube, and if her lungs can be kept relatively clear of obstruction, she may not need a ventilator to breathe and will be able to talk fairly well most of the time. She will have a permanent urinary catheter, and require suppositories or enemas for every bowel movement she has the rest of her life, and someone will put her into her wheelchair and take her out every day of the rest of her life, move her from place to place and give her special skin care to prevent sores from developing on her buttocks and hips. Hopefully, she will avoid getting pneumonia, or a bleeding stomach ulcer, and her family will be available to stay close and assist her indefinitely.

Cindy will come back to the ICU to visit us three months after her discharge, sitting in her wheelchair, pushed by her stepfather. She will have broken the engagement with Tom, or complied with his wishes—she’ll not want us to know exactly which. Her straight blond hair will have grown longer and be shiny and groomed and obviously her pride. And she will smile and smile when she sees us, and cry when we hug her one by one. She’ll tell us about her tutors and her plans for completing high school. The staff and I will be grateful for her visit and her thanks and after she says good-bye, we’ll turn back to our patients in their beds, turn to the paperwork which must be complete before shift ends. And though we’ll not see Cindy again, for years we’ll wonder what happened to her, how long she actually lived, how the family managed.

Before many more weeks pass, another patient will show up in our unit with such an injury, this time a young man who begs us to let him die though we won’t, and toward the end of the year, a forty-year old mother and by that time we’ll have the routine down: we’ll anticipate and avoid some complications, we’ll know what questions to ask and when to remain silent. We’ll know because a girl with wet blond hair and a bruise over her left eye began to teach us on the way home from her prom.

(The names of all individuals, families and medical and nursing staff in this essay have been changed to protect their privacy and honor confidentiality.)

Share this post with your friends.

This essay so beautiful and compelling! I could not stop reading–it propelled me straight through. Beautiful work, Rose, I am so grateful to have read it. It left me with tears in my eyes.

Thank you, Lynda, for reading and for your comment. So glad you found it moving. One of the profound experiences of my life.

What a lovely essay and heart-breaking piece!

Thanks, Erika. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Don’t know how I missed this back in February but glad I found it now … Such a beautifully written account of loving empathy I couldn’t stop reading, even though I should be working. Today’s pandemic has shown us how heroic nurses are every day. This essay illustrates nurses’ long tradition of delivering life-changing physical AND emotional care.