From an early age I enjoyed drawing, and in later years took up oil painting and etching as well. Eventually I decided to go into art full time, which I have continued to do, putting on paper images that simply come to mind, but also illustrating scenes from Dante’s Divine Comedy and other literary works.

In my mid-fifties I happened to pick up a copy of the Inferno, the first of the three sections of Dante’s The Divine Comedy (the others being Purgatorio and Paradiso) and found myself mesmerized by the poetry and the vividly portrayed scenes. T. S. Eliot, one of Dante’s great admirers, noted that Dante was an extremely visual poet, a quality attested to by the number of artists—from Botticelli to Blake to Dore to Dali—who’ve portrayed their impression of his journey through the Afterlife.

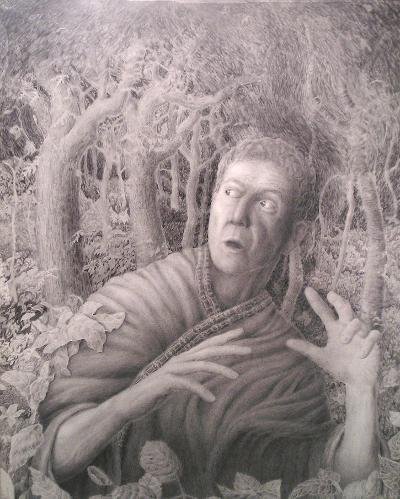

As I began reading Inferno, I was immediately struck by its opening. Here Dante writes lines that I later learned were among the most quoted.

“When I had journeyed half of our life’s way,

I found myself within a shadowed forest,

For I had lost the path that does not stray.”

What I tried to capture in this illustration was Dante’s admission in these and subsequent lines of how bewildered and overwhelming afraid he is.

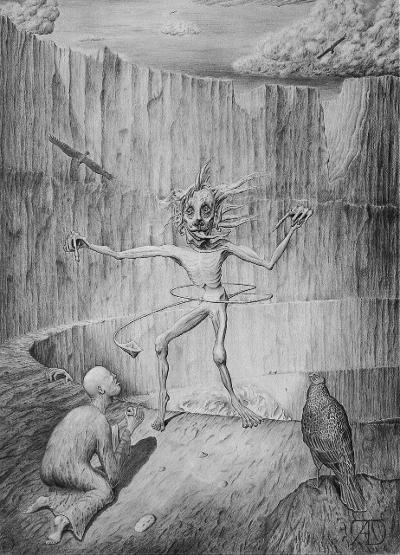

Shortly thereafter, Dante and his guide, Virgil, come across a creature called Minos (Inferno teems with wild creatures). Standing at the entrance to Hell, Minos has the task of informing each new sinner how far down in the pit that person has been assigned–and the further down, the more severe the eternal punishment. This seemed clear evidence of Dante’s vivid imagination as well as of his poetry’s embedded humor. As if it weren’t depressing enough to find oneself committed to Hell, I tried to think while doing the drawing how I might feel being further belittled by the way Minos delivers the news of one’s destiny:

“As many times as Minos wraps his tail

Around himself, that marks the sinner’s level.”

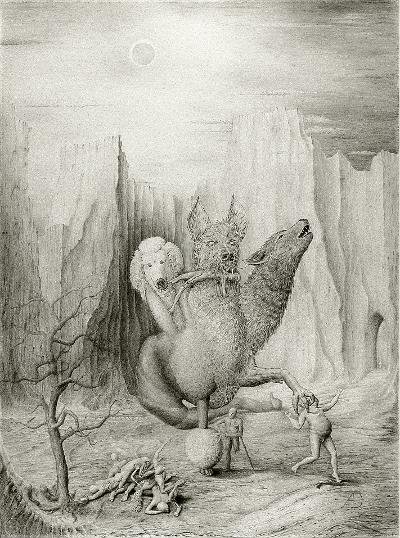

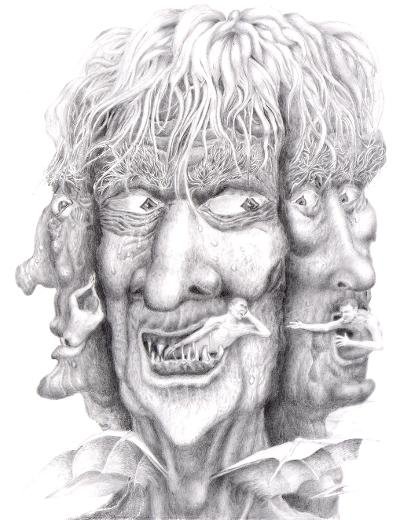

After passing through a number of Hell’s Circles, Dante and Virgil arrive at the Circle of the gluttons. Here they encounter a creature, Cerberus, who has three dog-like heads and whose “hands are claws, his talons tear and flay and rend the shadows” (i.e., the condemned spirits). Giving free rein to my imagination, I portrayed Cerberus in a decidedly modern guise.

Still further on in their descent, the two travelers reach the Circle where those who committed suicide are punished. While it seemed that these people should be among the last deserving punishment, the theology of Dante’s era argued otherwise. Regardless, it was the creatures who watched over these sad shadows that entranced me, The Foul Harpies. Sweeping over the landscape,

“Their wings are wide, their neck and faces human;

Their feet are taloned, their great bellies feathered.”

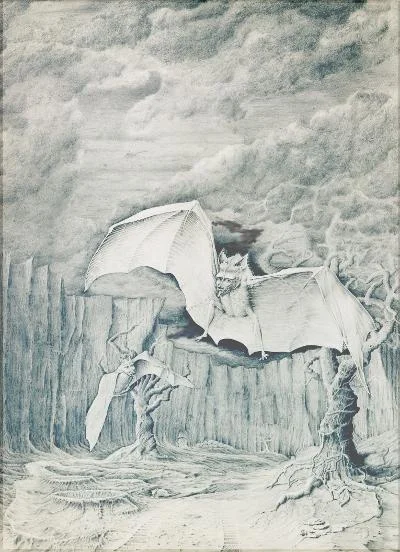

Reaching the very bottom of the pit, Dante and Virgil encounter someone who’s hardly a surprise—Lucifer. At first it wasn’t clear why he should be found punishing those guilty of treason when he himself was regarded as the most treasonous of all, having attempted to overthrow the Kingdom of God. But then it dawned on me that this had to be his own personal punishment, forced to brutalize those most like himself. It might be expected that he, being treasonous, would be described as double-faced. In fact, though, we are told he was more than that. He was three-faced! And

“Within each mouth—he used it like a grinder—

with gnashing teeth he tore to bits a sinner.”

After so much agony and strife, it seems only appropriate to present a more serene side of The Divine Comedy. One illustration is from Purgatorio, where the souls are guaranteed eventual admission to Paradise, and one from Paradiso itself. Because the atmosphere in Purgatorio struck me as more defined, more concrete that that of Inferno, I decided to do its illustrations as etchings. The one shown here takes place as Dante nears the peak of Mount of Purgatory where he experiences a series of visions. Many are reminiscent of some in the Book of Revelation—golden candlesticks, four Beasts of the Apocalypse, etc. but one is of a chariot drawn by a griffin, a creature with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion, which Dante saw as a reassurance of divine power.

In Paradiso, Dante enters a realm so overflowing with ecstasy that he finds it hard to describe. One such scene emerges in the Sphere of Venus, where a group of souls appear to sing and dance with abandon. Because of the brilliance that pervades all the Spheres of Paradise, I did this and other illustrations in oil.

T. S. Eliot was also a poet I came to appreciate only later in life. And he, being a great devotee of Dante, emphasized many of the same themes: sin, redemption, grace. For me these themes come through most clearly in the “The Four Quartets” which contains a few visions of Eliot’s own. One that may allude to Dante’s joyful souls on the Sphere of Venus is from the section called “Burnt Norton.”

“At the still point of the turning world . . . there the dance is.”

Presuming fire to be a refining element, and rose to represent the state of bliss, another of Eliot’s visions, which I found a profound proposal, also appears to harken back to his beloved poet.

“The fire and the rose are one”

Share this post with your friends.