I Like the Story

Of the watch my father gave

my mother

how it stopped whenever they fought,

except that is not

the full story, the whole one.

In the beginning

there was a hard-earned dollar

then another

and another in a jar.

And a jeweler in Hazard

on a bull hot summer noon, the boy

charging in, a gold chain

paid to his keeping,

and his face, which glowed

but did not show yet

that love is a stop-start thing

unwound and lapsed

into the silence of a drawer.

Collecting years of bitter dust,

only to begin one day, ticking

where it left off-

hands stuck on invisible zero.

This poem developed from one family narrative; a story passed down from my mother. Partly fact, I filled in the unknown and in doing so, reached inside the story for my own. I’m fascinated by family narratives as poetic genesis, their nearly mystical power to guide and restore us as we write and tell.

Generations of family stories are lost. Why? Because by the time children are old enough to ask, the elders are gone. Or the family is so distracted by electronics, acquisition, or just plain survival, they lose the dimensions of their own histories. And yet, according to some studies, a strong family narrative is the best cushion against trauma that a child will ever have.

Psychologist Marshal Duke (Emory University) developed a scale called “Do You Know?” which asks children twenty questions about their families. Do you know where your grandparents went to school? Do you know the story of your birth? Do you know how your parents met? These are some of the questions asked of the children of several dozen families in the wake of America’s 9/11 trauma, along with psychological tests. The overwhelming result was that the more children knew about their family stories and histories, the better they were able to moderate stress, and maintain a high sense of control over their lives. Interestingly in the article, closeness between family members is not central. Rather, it is the sense of belonging to something larger than oneself and knowing what that something is.

I don’t know whether our stories’ transmissions are an answer to the shootings, violence, and our crime epidemic of loners and loneliness. I do know that humans have tried to connect through stories for at least twenty thousand years, since the first cave drawings were discovered in the caves of France. Up came the stories through pictures, then oral traditions and various forms of verse. I’ve heard three versions of my grandfather’s death from coal mining injuries/heart failure; each of them is true. Each contains the metaphor (somewhere) that connects us across the ages.

Tell the stories

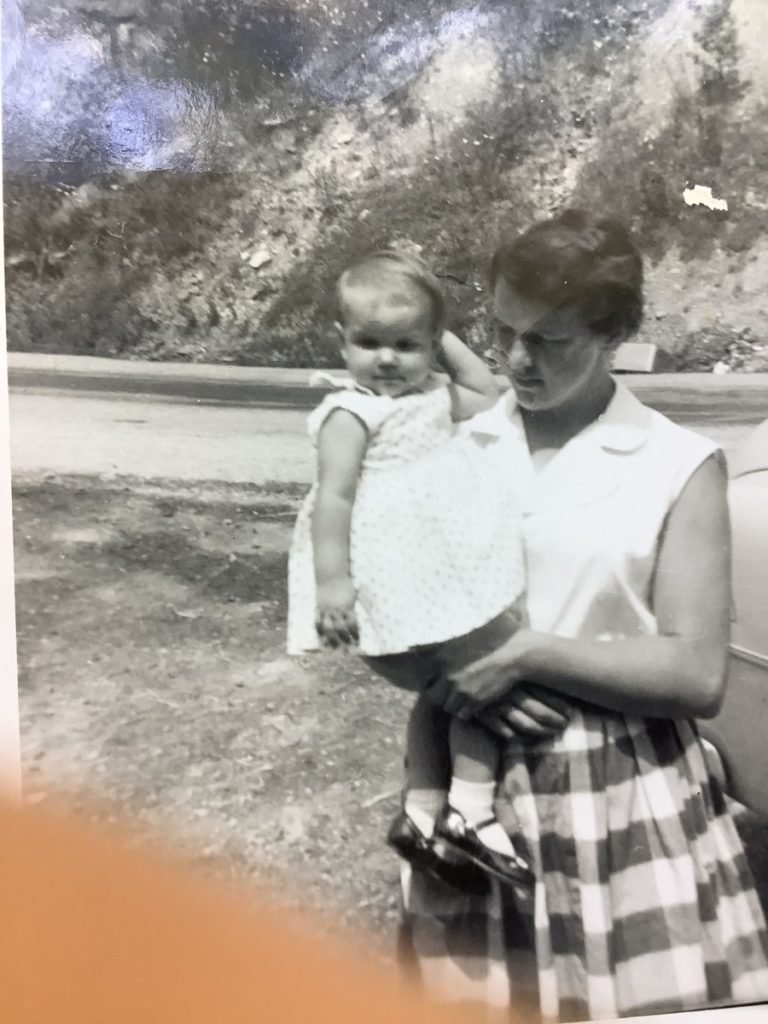

There is an old photo of my young mother carrying me by the roadside in southeast Kentucky. She is wearing a skirt because Pentecostals, at that time, did not believe in slacks. I am decked out in my first pair of patent leather shoes. We are squinting at each other in sunlight. No matter that we would never be this close again; there, against the backdrop of a mountain sheared and dynamite blasted by the coal company, the love was perfect and untainted. Falling Rock Zone. Never mind that she may have wanted to shove me off that mountain more than once as years passed without a word between us. Our story began before that, in a place where rockslides threatened behind us and religion chose our clothes, as we held onto each other as best we could.

Share this post with your friends.