When tracked down, Aaron Farrington was on a camping trip in the woods of Grayson Highlands State Park. We met soon afterwards in his basement studio in the McGuffey Art Center in Charlottesville. A photographer of many talents and technologies, his subjects include newts, frogs and mushrooms, smoke stacks spewing pollution, Mary Chapin Carpenter and Dave Matthews music videos, documentaries, and vintage wet plate portraits.

Farrington remembers growing up in Harrisonburg, Va. where, at fifteen, he was given his mother’s Pentax 35 mm camera and he started taking pictures. Around the same time, he became intrigued with movies and wanted to make his own. “It ebbed and flowed from when I saw Star Wars which I thought was amazing. When I was in high school Twin Peaks came on television, Wild at Heart and Van Sant’s Own Private Idaho came out. They seemed sort of different and mysterious and hinting at a world that I didn’t know anything about, being fifteen or sixteen years old,” he says.

While working on the school newspaper, Farrington learned to make unique double exposures. “I’ve always been more interested in capturing the way something feels to me. It’s never been about trying to be weird or look scary.”

Farrington, on the lookout for fresh and arresting images, went to New York University’s film school. He dropped out after two years and wrote a novel. He laughs. “I think writing that novel sort of beat writing out of me.”

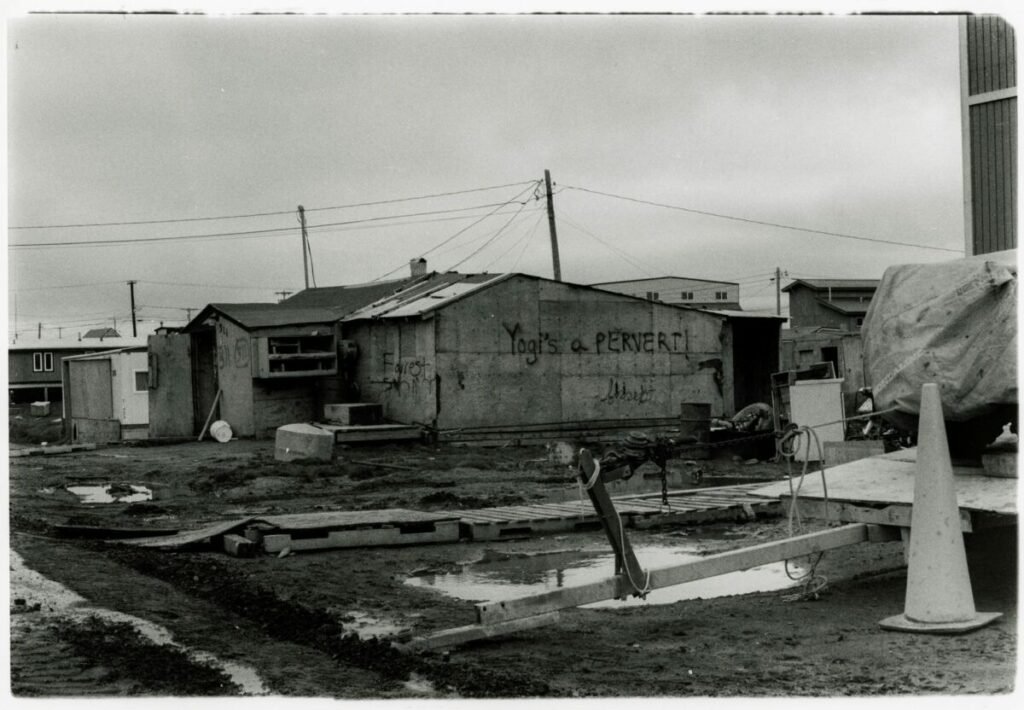

He moved to Charlottesville in 1997 and would consider it a home base for years to come. In the meantime, he was often on the road documenting what he saw across the country from Los Angeles to Barrow, Alaska on the coast of the Arctic Ocean. “I took pictures of whales and one of Inuit children dancing on the back of a fifty-five foot long whale that had been caught and killed and dragged up onto the beach. Barrow was beautiful when the sun was shining, but usually the sky was flat and grey and the ocean was flat and the land was flat and grey.”

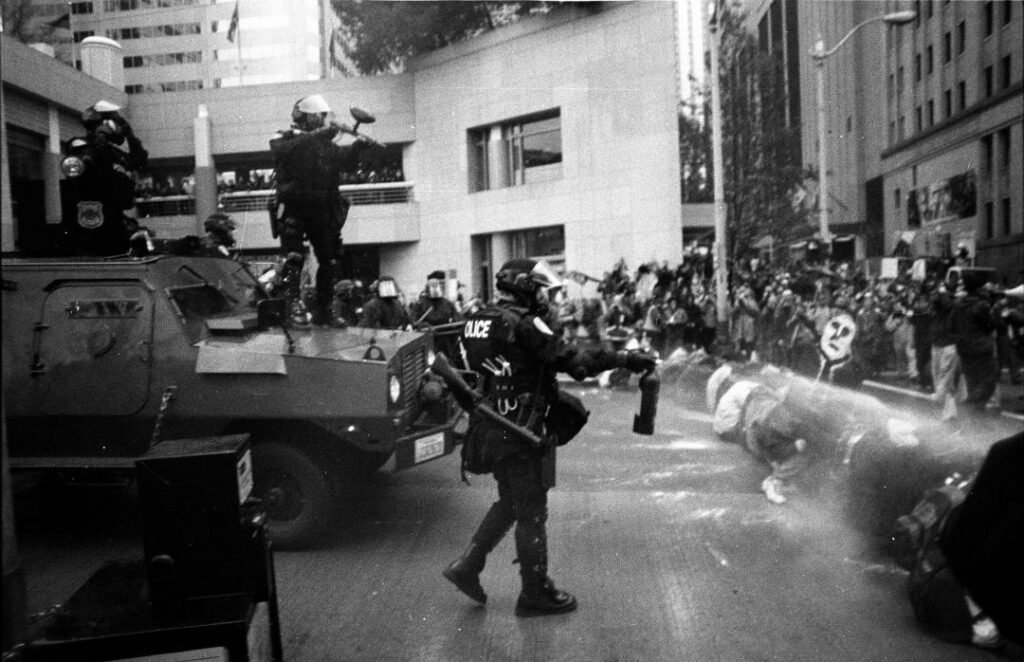

In 1999 Farrington met Dave Matthews, leader of his famous rock band. Together they attended protests that disrupted the World Trade Organization Ministerial conference in Seattle. A broad coalition (students to labor groups) protested anti-globalization trade policies. “I think I was looking for some sort of dissent; something different,” says Farrington.

“I was driving all around the middle of the country and not finding it. At the WTO there were all these environmentalists, and anarchists protesting what they thought was wrong. Dave and I went down to the protests and got ourselves tear gassed together. He’s been nice to me ever since.”

It wasn’t until many years later that Farrington started working for the band. By then, he had documented the Hackensaw Boys Band’s first North American tour. In 2003, Farrington directed and produced a documentary on the North Mississippi All Stars and the Hill Country Blues. “Do it Like We Used To DO” features RL Burnside and Jim Dickenson and is a raw, unflinching portrait of a landscape, its music and a band.

He also directed a feature length film for Boyd Tinsley, former violinist and mandolinist with Matthews’s band. “The band was utilizing more video in the stage design so I started out just making videos for their video wall behind them, incorporating it into the stage show. I still do that,” he says. Together, he traveled with the band to South Africa and around the U.S.

In 2013, Farrington came up with the concept of “Rooftop,” a wild romp music video that he describes as One Flew Over the Coocoo’s Nest meets King Kong. “It was super fun because that dude, Dave, is a great actor. He’s super talented with everything.

“Being on the road was fine except when it was also terrifying. I thought I’m going to slip on stage, hiding behind Stefan’s (Lessard) bass or taking pictures of Carter (Beauford), the drummer. It was fun but it was work.”

Farrington often returned home from a weekend of concerts with as many as six thousand (digital) pictures, three thousand a night. “I’d come kind of late to digital photography. I’d shot film for a long time, and I didn’t want to be one of those people mindlessly taking pictures.

“You can’t take three thousand pictures a day. I said to my wife, ‘I’ve got to take less pictures.’ I showed her a wet plate picture and said ‘I want to make pictures like this.’ Wet plate pictures you can make three in an hour. She said, ‘well do it.’ ‘But I don’t know how.’ ‘Well, figure it out.’”

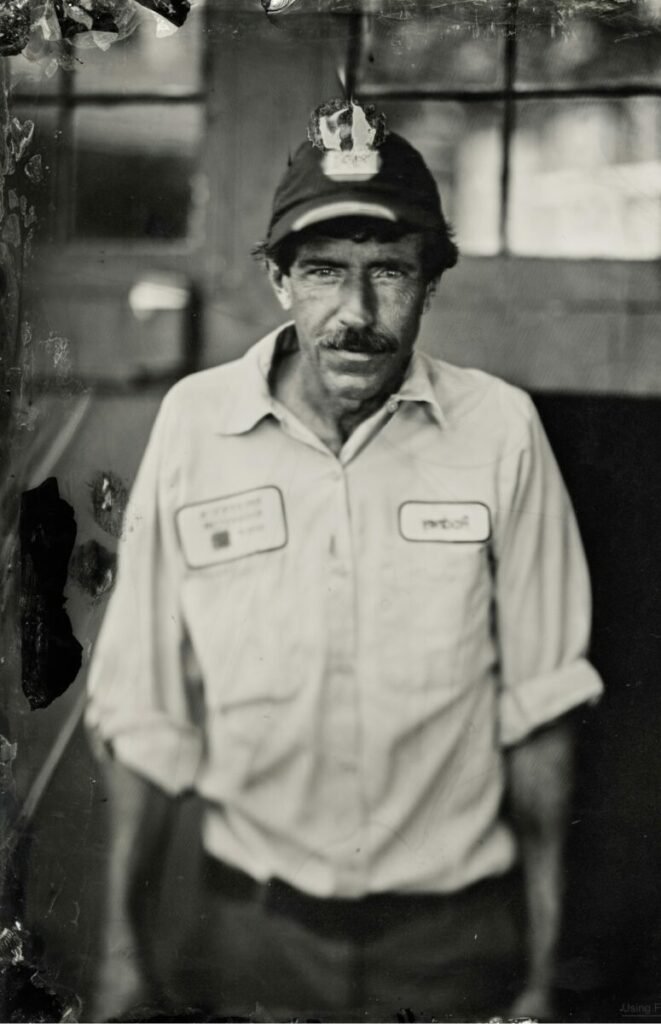

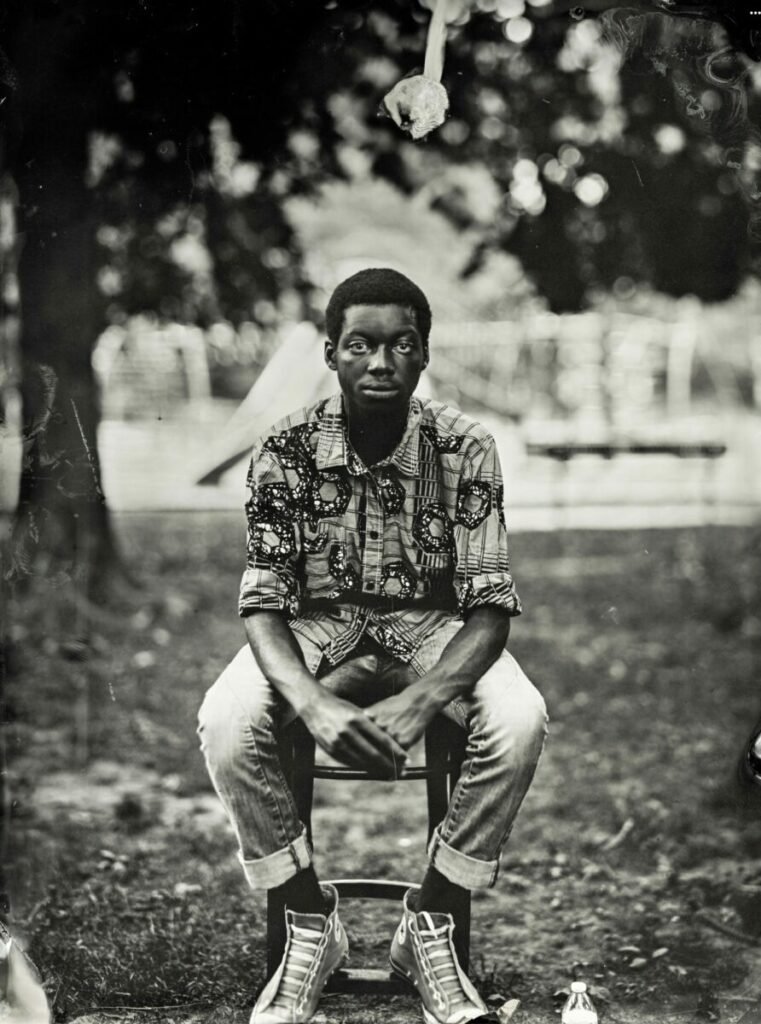

And so he did. In 2014, Farrington found a 1910 8×10 camera on eBay and added another technique to his roster. Wet plate photography involves soaking a piece of tin or glass with silver nitrate, putting it in the camera and exposing it. He shoots the picture and has to develop it before the plate dries in a portable dark box of his own making. It’s a chancy procedure that, if done correctly, can bring instant results.

“Now I take ten pictures a day, if I’m lucky,” he says. “The portraits seem more like a collaboration between me and the subject. If I do everything right, it’s still not much of a picture unless they do everything right too. Then it can be a good picture even if I mess stuff up.

“I take ordinary people and photograph them like they’re the most important person on earth, says the admirer of Robert Frank’s iconic The Americans and Edward Curtis’s early documentation of Native Americans.

Farrington now shoots a lot of videos along with digital photographs of nature. He creates intriguing time lapse videos of creatures and flora and fauna he discovers on the forest floor.

He recently finished a reflective video for “A Bad Think,” a Virginia Beach band, and completed stills of members of the Dave Matthews band for a new album. His music video, “Our Man Walter Cronkite,” with Mary Chapin Carpenter, is a poignant meditation on past times of truth and upheaval.

“There’s not a whole lot of money in making large pictures of small mushrooms so making visual candy for rock and roll shows video screen takes up a lot of my time,“ he says.

Calling his company To The End of the World Pictures, Farrington’s closeup nature shots seem counter weight to images of industrial pollution—nuclear power, power plants to abandoned cars and buildings. ”I don’t think of myself as an environmentalist,“ he says, “but It makes sense that you’d want to live in a sustainable way. I don’t see it as ‘beautiful pollution.’ It doesn’t make me feel good when I see it. It makes me feel good to take pictures of mushrooms and flowers.”

Giant sized prints of mushrooms and flowers hang next to wet plate portraits in Farrington’s cluttered studio. “I shoot them like they’re they’re the biggest thing in the world; I like to give them hero like status.”

Farrington was gearing up for another camping trip with his wife and seven year old daughter. “I spend a lot of time on my belly in the woods with my macro lens trying to make panoramic and macro pictures,” he says.

“There’s sort of a rhythm of life right now . . . winter and spring is a lot of video work and then my goal for the summer is nature, exploring and playing. Since my daughter started going to school, all of sudden my summer sort of reminds me of being a kid again. In the fall I try to do some work on the house, and then winter is back to work and making money. A friend said to me, “You just need to pick a lane and do that.” I’m trying to prove to her I could do everything all together, all at once.”

— by Elizabeth Howard, Streetlight‘s Art Editor

Share this post with your friends.

Your famous Aaron and an awesome recorder of life in every size….❤️